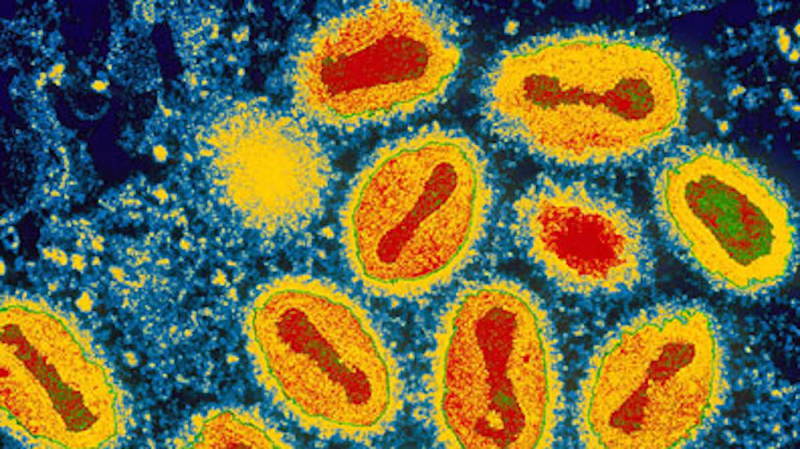

Smallpox

Source: BBC

Smallpox has no known treatment or cure. There is a vaccine to prevent smallpox infection, but the side effects are too bad to justify inoculating low risk populations.

Only about 30% of cases result in death, and it’s relatively difficult to catch without incredibly close contact with an infected person (smallpox can be transmitted through droplets in the air, or contaminated bedding or clothing). But for the unlucky few who do come down with it, smallpox is a slow, painful death.

Source: Wikipedia

For the first 12 or so days, you’ll look and feel completely healthy. Then, you’ll start experiencing flu-like symptoms. Fast forward a few days, and lesions will appear on your face, hands, forearms, and they’ll eventually spread to your whole body.

The lesions turn into pus-filled blisters, which scab and then scar. The blisters on your mucus membranes (the insides of your nose and mouth) will be the most painful, and eventually, they will burst, spreading the virus through your saliva.

It’s the presence of the virus in the blood, and resulting clotting in capillaries and blood vessels, that eventually kills its victims, and it’s no fun.

Lucky for us, smallpox was successfully eradicated in 1979, and only two laboratories retained samples–one in the United States, and one in Russia. Here’s to hoping both facilities have good security.

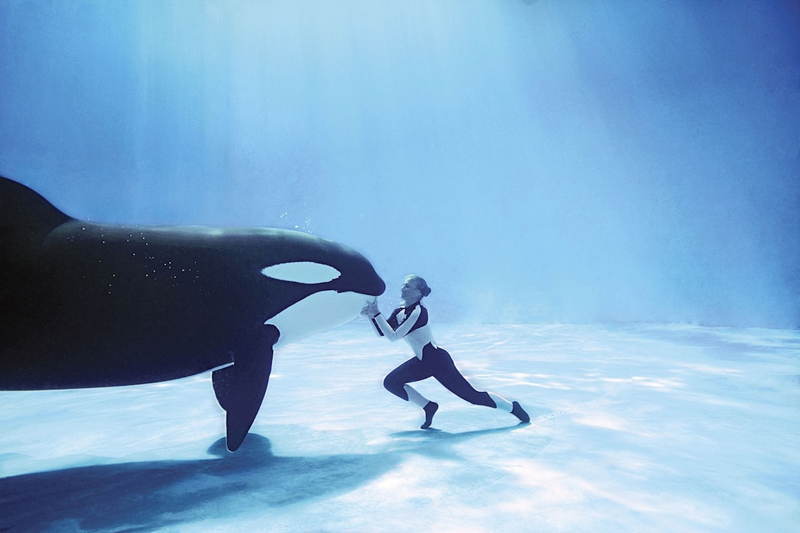

Dismembered By A Captive Orca Whale At SeaWorld

Source: All Pet News

Like elephants, orca whales are incredibly intelligent and highly social creatures. This means that death at their fins can often be drawn out and intended to inflict the maximum amount pain and humiliation. According to orca researcher Howard Garrett, orcas have never been known to harm a human in the wild, but killer whales kept in captivity are far more likely to live up to their name.

Source: NBC News

Neuroscientist Lori Marino has studied orca brains and concluded that they have “highly elaborate emotional lives [which are] stronger and more complex than in humans.” What this means is that separating orcas from their family groups, depriving them of food as a punishment for bad behavior, and confining them, oftentimes alone, to small tanks results in similar types of behavior humans under the same conditions are known to exhibit (i.e. hyper-aggression and a tendency towards violence and killing).

Except these conditions are more detrimental to the whales than they are to humans, because a wild orca travels upward of one hundred miles a day, and his sense of self is not contained within the individual, but distributed throughout his entire pod.

The artificial groupings we see at amusement parks like SeaWorld are not an adequate substitute for the whale’s family group, since individuals from different pods use unique languages and follow different sets of customs. It would be the equivalent of throwing five people with no common language or culture into a 10×10 room, locking the door, withholding food, and expecting them to get along.

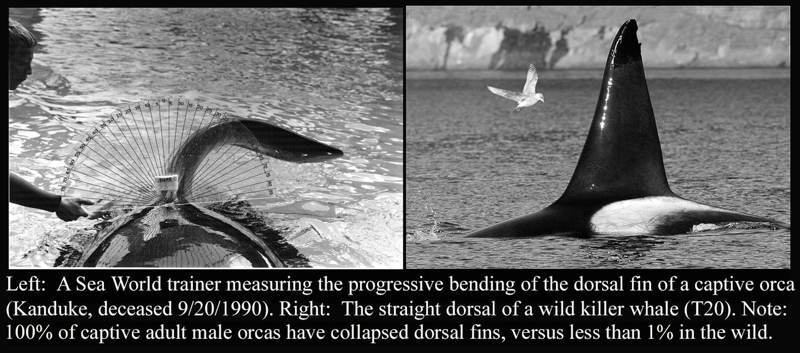

Source: The Orca Project

Captive orcas have been known to turn on their trainers–holding the helpless human underwater for minutes at a time, allowing the trainer to surface for a moment, only to drag him down again over and over again.

In 1999, a man who snuck into an orca’s tank at SeaWorld was found dead the next morning. He’d been stripped naked, castrated, bitten repeatedly, and the whale paraded the dead man’s body around on his back for all the staff at the park to see. The same whale would later attack and kill one of his trainers.