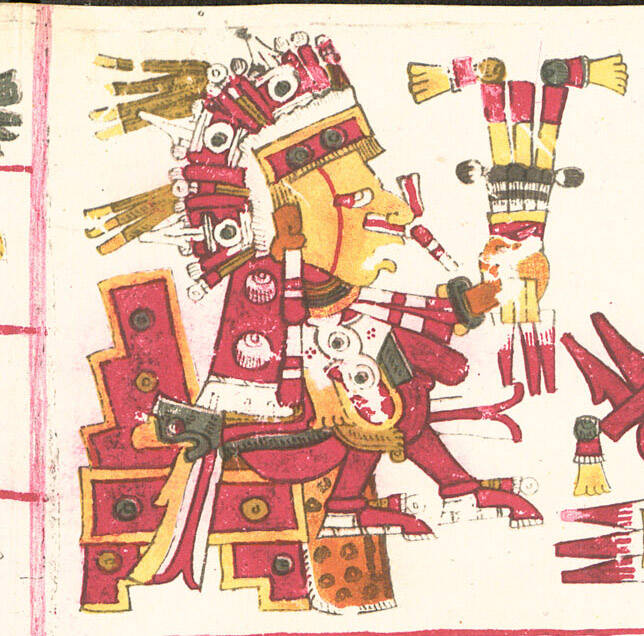

Ceremonies honoring Xipe Totec were often brutal, involving human sacrifices and skinning of corpses, but the deity was also revered as a god of spring and rebirth, with the human skin seen as merely the husk that harbored the seed of life within.

Wikimedia CommonsXipe Totec, or “Our Lord the Flayed One,” is said to have been the god of spring, seeds and planting, and metal workers.

Mesoamerican cultures worshipped a litany of gods that stand out as unique, even among other ancient polytheistic cultures. Few, however, are quite as unique — or frightening — as Xipe Totec, or the “Flayed One.”

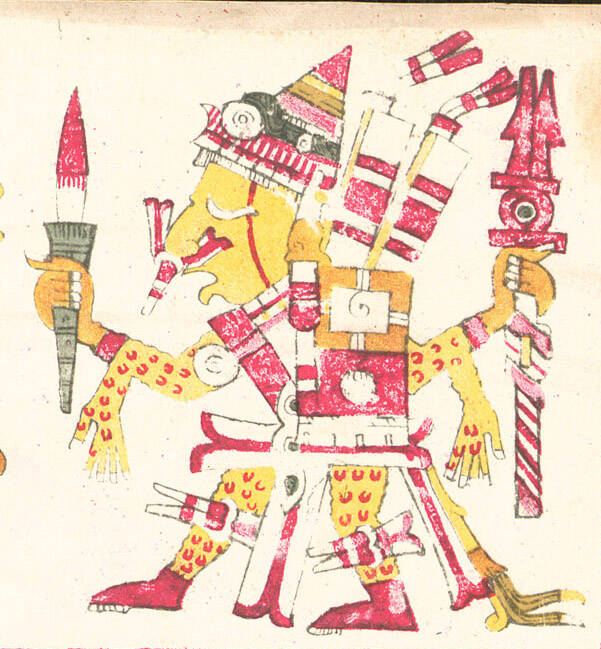

Xipe Totec was a particularly important deity among the Toltec and Aztec cultures, where he was revered as the god of spring, the patron god of seeds and planting, and the patron of metal workers and gemstone workers. But while these associations seem rather wholesome, the rituals surrounding Xipe Totec were anything but.

As a symbol of the new vegetation, or “new skin,” that coated the Earth each spring, Xipe Totec wore the skin of a human sacrifice — and depictions of the god usually show him wearing freshly flayed skin. There were several rituals dedicated to Xipe Totec, each involving human sacrifice.

Here’s everything you need to know about Xipe Totec, “Our Lord the Flayed One.”

Xipe Totec’s Place In Mesoamerican Mythology

There are several possible points of origin for Xipe Totec. According to the World History Encyclopedia, some historians believe Xipe Totec may have originated with the Olmec culture, who established what was likely the first Mesoamerican culture along what is now the Gulf of Mexico and the coast of Veracruz. Others suggest Xipe Totec’s origins lie with the Yope civilization of the Guerrero highlands.

It wasn’t until around the ninth century C.E., however, that we begin to see representations of Xipe Totec in art, particularly with the Mazapan culture at Texcoco.

By this point, numerous Mesoamerican cultures had begun to worship the god in some form, including the Aztecs, Tlaxcaltecans, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Tarascan, and Huastecs. Representations of Xipe Totec can be found among some later Maya cultures as well, with his likeness appearing in art found at Chichen Itza, Mayapan, and Oxkintok.

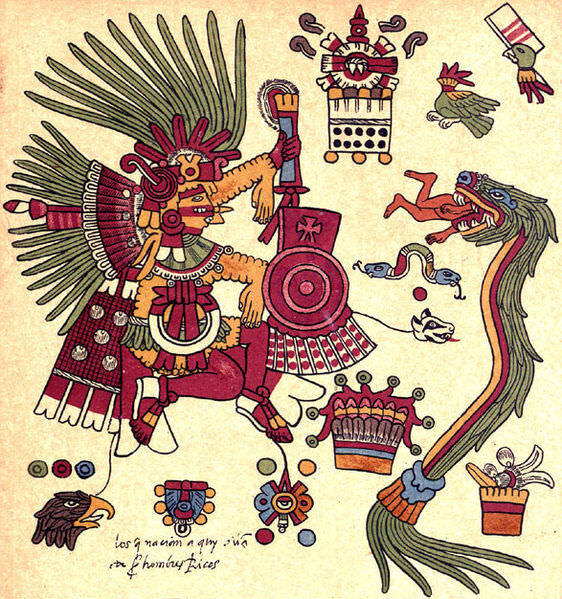

Public DomainVarious iconography associated with the Mesoamerican gods, including a depiction of Xipe Totec on the left.

But just who was this god to the Mesoamerican cultures, and why was worship of him so prevalent?

According to Mesoamerican mythology, Xipe Totec was the son of Ometeotl, a primordial androgynous god who eventually split into two, Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, to produce all creation. In Aztec lore, Xipe Totec was also the brother of three major gods: Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli, and Quetzalcóatl.

Each of these gods was central to Aztec mythology. Tezcatlipoca was associated with the night sky, hurricanes, obsidian, and conflict; Huitzilopochtli was the patron god of the Aztecs and had strong associations with the sun and war; and Quetzalcóatl was the god of the morning and evening star, later known as the patron saint of priests, the inventor of books and the calendar, and a symbol of death and resurrection.

Like Xipe Totec, some rituals dedicated to these deities involved human sacrifice. As a result, each of them was in some way associated with death.

In the case of Xipe Totec, it was believed that he was the source of disease among humanity, and so many sacrifices made to him were either to prevent or cure illness.

Tlacaxipehualiztli, The Gruesome Festival Dedicated To Xipe Totec

During the second month of the Aztec Year (roughly around April), worshippers of Xipe Totec held a festival known as “Tlacaxipehualiztli,” or The Flaying of Men. As the name would suggest, this festival was rather gruesome.

As explained by JSTOR Daily, The Flaying of Men was a month-long festival — 20 days, in the Aztec calendar — during which captives, usually prisoners of war, were prepped for sacrifice through a series of elaborate dances and a ritual haircut.

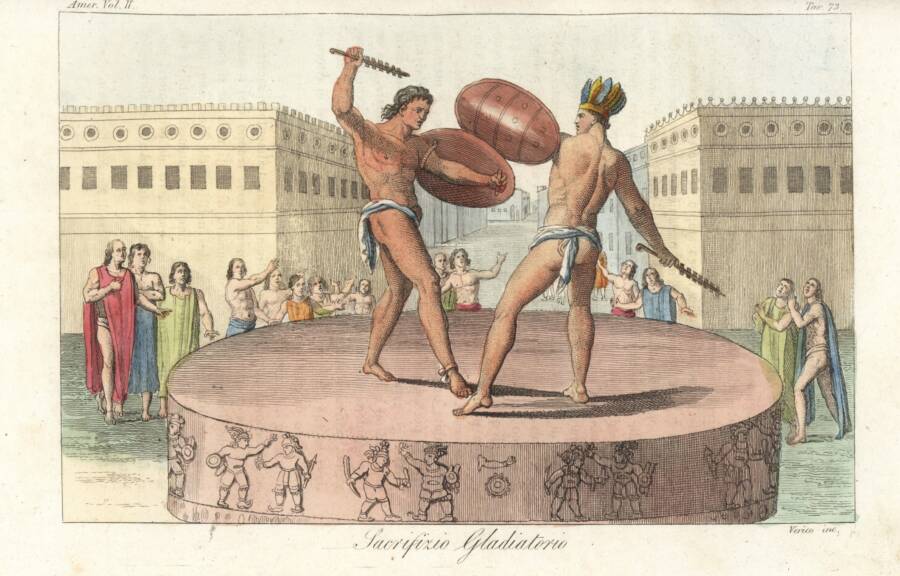

Album/Alamy Stock PhotoA gladiatorial sacrifice to the Aztec god Xipe Totec.

On the festival’s second day, the captives were forced to fight against well-armed combatants. Those who showed particular bravery, either by winning their rigged contests or walking proudly to their deaths, were honored during the festival.

Of course, they were still sacrificed in the end. Usually, this sacrifice included removing the captives’ skins and hearts and offering the hearts to the sun. Sometimes, their bodies were partially consumed.

The flayed skins were then worn by young men referred to as Tototeci or Xipeme, “The Skinned Ones,” who donned the flayed skins for the entirety of the festival as they paraded through the city and engaged in mock conflicts. Spanish observers who later recounted the festival described that, by the 20th day, the skins were in horrendous condition.

At the end of the 20th day, the Xipeme enjoyed a feast and finally removed the flayed skins, burying them in a cave beneath the city’s central temple.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of Xipe Totec, in which he can be seen wearing freshly flayed skin.

Another heavily involved practice preceded the festival, however. For 40 days, a member of the community dressed as Xipe Totec, adorned in bright red feathers and golden jewelry. Other impersonators dressed as Mesoamerican mythology’s eight other major gods, including Quetzalcóatl. Then, on the festival’s first day, these impersonators were sacrificed and skinned.

Their skins were dyed yellow and called “teocuitlaquemitl,” golden robes worn by priests during ritual dances and ceremonies or donned by the “skinned ones.”

While these rituals may seem gruesome by modern standards, the Mesoamericans attributed great reverence to wearing another’s skin. The act was meant to symbolize the rejuvenation of the Earth each spring and to know what it means to live as a seed inside a husk, much like an ear of corn.

Grim Depictions In Art

In art, Xipe Totec is often portrayed wearing the freshly flayed skin of a sacrifice. Mesoamerican cultures worshipped him as a symbol of life emerging from the dead land and of new plants sprouting from seeds.

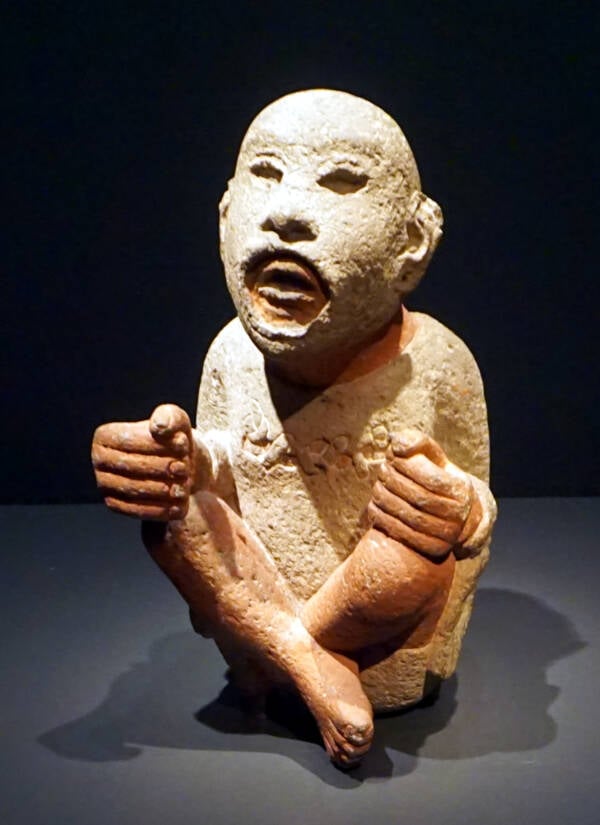

Wikimedia CommonsA stone statue of Xipe Totec.

Depictions of Xipe Totec can be found across various mediums and cultures throughout Mesoamerica. He is often seen portrayed in paintings, sculptures, and masks. His face appears bloated and grotesque in many depictions, with the flayed skin clearly tied behind the back of his head.

Many representations also show an incision over the heart, where sacrifices’ hearts were removed. Some portrayals also show Xipe Totec holding the heart of the sacrifice.

It may seem strange from a modern perspective that such a terrifying and gruesome god was immensely popular among Mesoamerican cultures. Still, the concept of human sacrifice was prevalent in many parts of the pre-modern world.

Moreover, these cultures did not view human sacrifice as the end of one’s life but rather as an offering to a higher power and, in some cases, even an honor.

If one’s life could gain a more profound meaning after death and benefit the community, it seemed far less cruel than we might imagine. Many cultures also believed in reincarnation and did not see death as the ultimate end.

Still, it is perhaps best that some practices associated with gods like Xipe Totec, like human flaying, are nothing more than remnants of a bygone era.

After reading about this Mesoamerican god and the rituals dedicated to him, learn about the gory legend of Huitzilopochtli, one of the most important gods in Aztec mythology. Or, dive into the disturbing history of flaying across the world.