One of the most important gods in the Aztec pantheon, Quetzalcoatl was associated with wind, wisdom, and agriculture and was believed to have invented the calendar, discovered maize, and even created humankind.

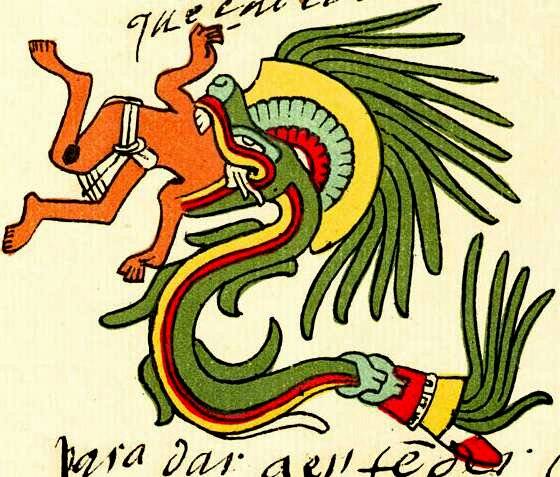

Codex Telleriano-Remensis/Bibliothèque Nationale de FranceThe Aztecs credited Quetzalcoatl with creating humanity.

Quetzalcoatl was one of the most prominent gods in the Aztec pantheon. Worshiped as the deity of wind, goldsmiths, and knowledge, the feathered serpent was linked to the rising morning star of Venus and protected priests and merchants.

The Aztecs also credited Quetzalcoatl with creating mankind, bringing about the current fifth age. According to the ancient Mesoamericans, there wasn’t much the god couldn’t do.

And while the Aztecs were known for honoring their gods through human sacrifice, Quetzalcoatl purportedly didn’t believe in the act. Instead, he required sacrifices of hummingbirds and butterflies.

However, the Aztecs weren’t the only — or even the first — culture to worship the deity.

The Evolution Of The Feathered Serpent God

The name Quetzalcoatl comes from two words in the Aztec Nahuatl language: quetzalli, which means “tail feather of the quetzal bird,” and coatl, the word for snake. Quetzalcoatl, then, was a feathered serpent unlike any other god.

Myths about a plumed serpent deity date back to the Olmec civilization, which flourished from 1600 B.C.E. to 350 B.C.E. However, Quetzalcoatl transformed into one of the most important Mesoamerican gods during the Toltec and Aztec eras.

During the Olmec era, Quetzalcoatl was depicted as a serpent covered in feathers. Centuries later, the god evolved into a human figure who wore a plumed headdress.

Diego Delso/Wikimedia CommonsThe Temple of the Feathered Serpent in the ancient city of Teotihuacán dates back to the second century C.E. and is decorated with plumed snake heads.

Around 1000 C.E., the Toltecs ruled Mesoamerica from their capital at Tula. The Toltecs constructed pyramids and temples to venerate Quetzalcoatl. At the ancient city of Cholula, the Great Pyramid was dedicated to the god and became known as his home.

Celebrations of the powerful god spread his fame across the region, with the Maya joining in and dedicating a temple at Chichén Itzá known as El Castillo to Quetzalcoatl, whom they called Kukulcan. The K’iche’ of present-day Guatemala also worshiped him at Gucumatz.

When the Aztecs rose to power in the 14th century, they expanded Quetzalcoatl’s abilities. They worshiped him for inventing the calendar, discovering maize, and bringing rain clouds, giving him a critical role in the agrarian culture.

To the Aztecs, Quetzalcoatl was the patron of science, craftsmen, artists, and agriculture. He even played a key role in the culture’s tale of how the world came to be.

Quetzalcoatl And The Aztec Creation Myth

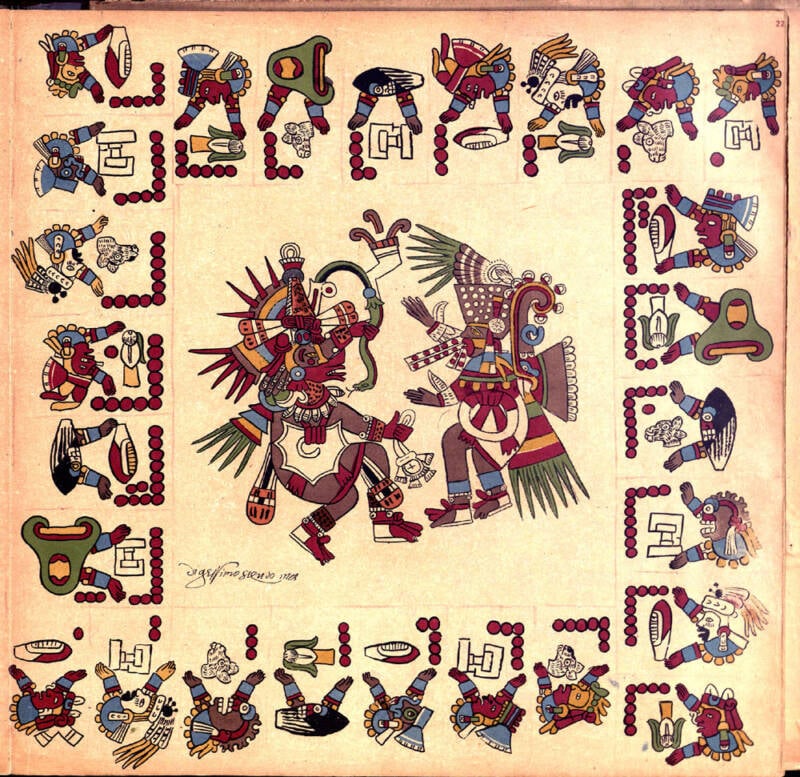

The Aztecs transformed the serpent god into the creator of the world. According to the civilization’s creation myth, Quetzalcoatl was one of the four children born to Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl along with his brothers Tezcatlipoca, Xipe Totec, and Huitzilopochtli. Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca were then told by their parents to bring order to the world.

The brothers found themselves in fierce competition, destroying entire ages of humanity during their fights. Aztecs claimed that the first age ended after Quetzalcoatl bashed his brother with a stone club, and his brother retaliated by sending jaguars to consume the world. Again and again, the brothers destroyed their creation.

Codex Borbonicus/Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican StudiesAn illustration of the Aztec gods Quetzalcoatl (left) and Tezcatlipoca (right) that predates the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century.

By the fifth age, the brothers found harmony, creating the Sun and Moon along with the land. In order to create the Earth, the brothers transformed into enormous snakes to defeat a reptile monster.

After perfecting the world, Quetzalcoatl journeyed to the underworld to create humanity. He also helped the first humans survive by gifting them with maize.

How The Serpent Deity Created Humanity

British MuseumA turquoise mosaic mask known as the Mask of Quetzalcoatl.

Tales of Quetzalcoatl’s deeds grew lofty in the Aztec era. The plumed serpent god even received credit for creating humanity.

According to Aztec myth, Quetzalcoatl traveled to the underworld, Mictlan, to collect the bones of ancient humans and form a new race of man for the fifth age of humanity. But before he could leave with the bones, the god had to pass an impossible test crafted by Mictlantecuhtli, the lord of the underworld. He gave Quetzalcoatl a conch shell with no holes and told him to blow it.

Instead of abandoning his task, Quetzalcoatl called on the worms and bees to help him. The worms made holes in the conch so that bees could fly inside and make the conch sound.

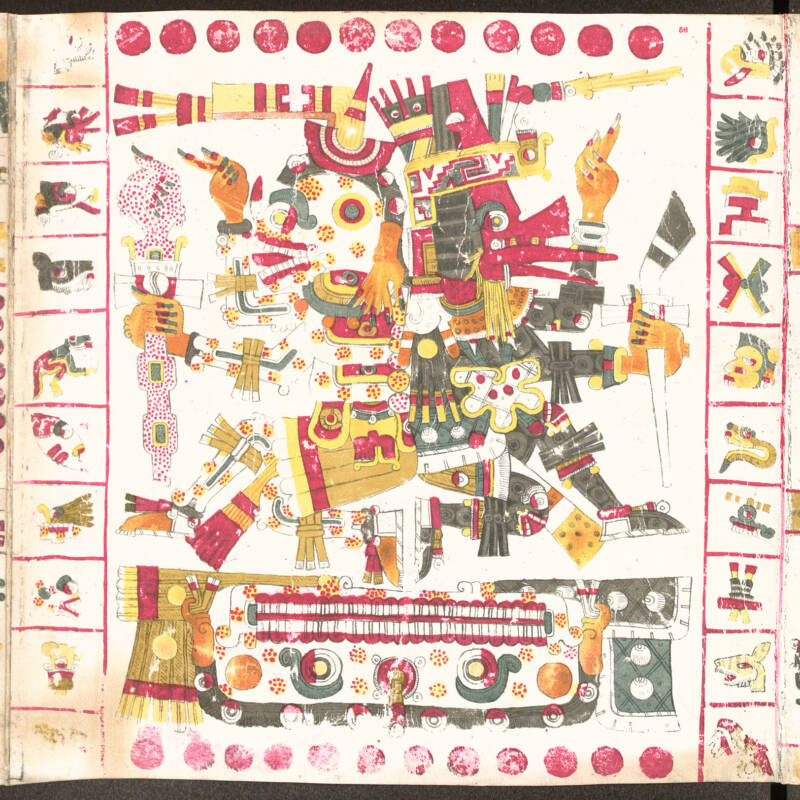

Codex Borgia/Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican StudiesQuetzalcoatl, shown on the right of this pre-Columbian codex, represented second life.

The clever solution allowed Quetzalcoatl to escape one trap, but that wasn’t the end of his troubles. When sneaking out of the underworld, the serpent god fell into a pit meant to stop him. Quetzalcoatl eventually managed to make it out with the bones, but he broke them in the process.

The great snake goddess Cihuacoatl transformed the bones into humans by blending them with corn and Quetzalcoatl’s blood. According to the Aztecs, people today are different heights because some of the bones were broken.

But that wasn’t the only gift Quetzalcoatl gave humanity. After creating the first humans, the god also found food for them to eat.

The Aztecs claimed that their plumed serpent god turned himself into an ant and followed a line of other ants over a mountain to a secret stash of corn. He then carried it back for the humans to eat. As a result, the Aztecs praised Quetzalcoatl for bringing maize to their ancestors.

While Quetzalcoatl played a key part in the story of Aztec creation, some tales also claim he had an equally major role in its downfall.

Did The Aztecs Really Believe Spanish Invaders Were Quetzalcoatl?

The Spanish conquest destroyed much of the Aztec civilization. But tales of Quetzalcoatl survived.

However, the arrival of the Spanish did twist the legends of Quetzalcoatl. According to one pervasive myth, the Aztecs confused the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés with their serpent god, leading to the downfall of their civilization.

As the tale goes, when Cortés arrived in Mexico, the Aztecs believed he was the god Quetzalcoatl, who had vanished in the east generations earlier. Instead of fighting the Spaniards, Emperor Moctezuma II handed over his empire to the returning god. There’s just one problem — the entire story is made up.

In fact, according to Ancient Origins, the Spanish conquistadors helped spread this myth in the 16th century. They heard Mesoamericans call them teotl, a Nahuatl word that can mean god. Spaniards spread the story that the Aztecs were so impressed with the Spanish that they confused them for gods. But teotl could also mean powerful. And the guns and horses that the Spanish invaders brought were certainly impressive to the Aztecs.

Yet Spanish chroniclers spread the mistranslation as proof that their invasion was God’s plan — and that the Aztecs themselves recognized it as God’s work.

Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional De EspañaA depiction of Quetzalcoatl on his raft made of snakes.

Decades after the fall of the Aztec empire, some Mesoamericans also spread the story that the Aztecs had not lost because of their inferiority but because they hoped the strangers on their shore were gods rather than invaders.

Today, Quetzalcoatl symbolizes Mexico’s national pride in its long history, and the plumed serpent god remains an important part of the Indigenous Mesoamerican tradition.

After reading about the powerful Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl, go inside La Noche Triste, when the Aztecs almost thwarted their Spanish invaders. Then, read about the Aztec death whistle, the instrument said to make the most terrifying sound in the world.