Hernán Cortés almost lost his hold on the Aztec capital when the natives revolted.

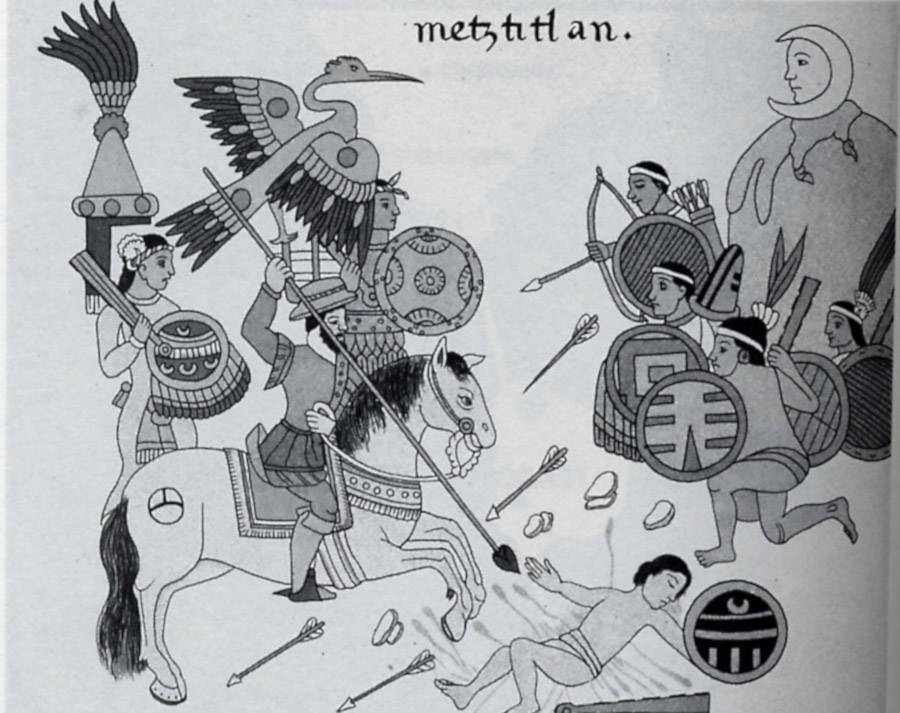

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of La Noche Triste.

Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés wanted it all: glory for Spain, personal recognition from the king and queen, fame, and fortune. Instead, he almost lost everything in one dramatic night on June 30, 1520, known as La Noche Triste or “Night of Sadness.”

Cortés and his troops had beat a hasty retreat from central Mexico’s Aztec capital after supposedly killing their emperor — and the Aztecs were pretty miffed about it. Thus, a massacre of the Spanish conquistadors began.

Cortés And His Lust For Riches

Cortés was a Spanish noble who sought further wealth and prestige in the New World. He helped to conquer the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola in the 1510s and so the governor of Cuba, Velázquez de Cuéllar, appointed Cortés captain-general of an expedition to sail to the American mainland in 1518.

Wikimedia Commons A young Hernán Cortés, conqueror of Mexico.

But Velazquez soon rescinded his order and Cortés was legally prohibited from setting sail for the American mainland. But Cortés was determined and he sailed to Mexico anyway — with a force of 500 soldiers, 100 sailors, and 16 horses.

He landed at Tabasco in Mexico’s Bay of Campeche in 1519 and was given a female slave by the locals whom he had wooed. That slave became his mistress and mother to his child. She spoke both Maya and Aztec which she interpreted for Cortés as the expedition continued up the Mexican coast.

Upon landing on in present-day Veracruz, Cortés burned his ships to ensure loyalty from his troops. There would be way out of the power-hungry conquistador’s scheme.

Before La Noche Triste

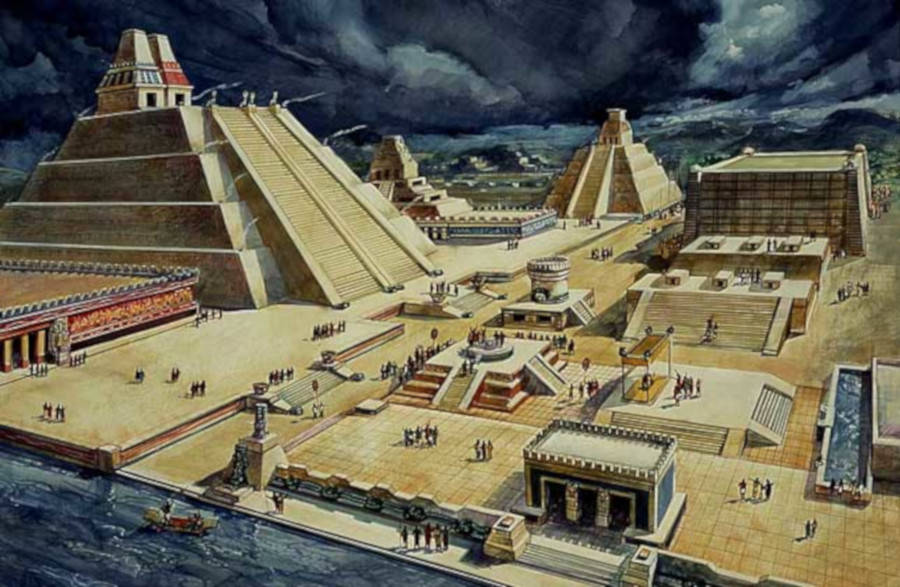

Meanwhile, the Aztec Empire flourished. Its capital, Tenochtitlan, was a technological wonder for its day. The empire thrived on its system of agriculture that included complex irrigation canals to send water to vital crops. In just 100 years — from 1325 to the early 1400s — Tenochtitlan had become the seat of power for the most advanced civilization in Mesoamerica.

The Aztecs themselves, however, were feared and disliked by many.

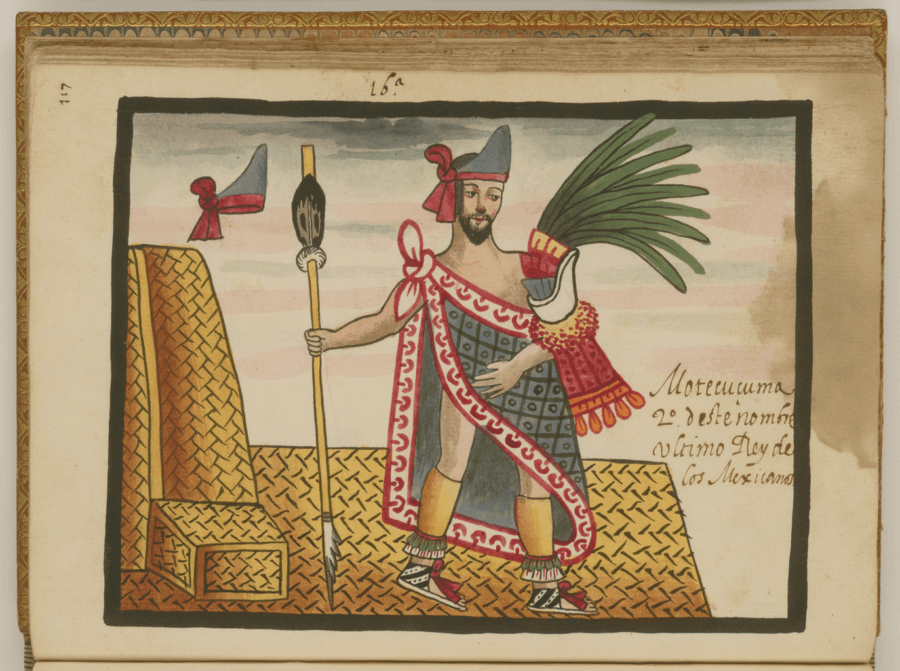

Wikimedia CommonsDepiction of Montezuma II, the last king of the Aztecs.

Emperor Montezuma II’s military kept an iron grip on outlying tribes. He forced surrounding tribes to pay him tribute and less advanced tribes were tasked with supplying him with human sacrifices for religious ceremonies. In the midst of this internal unrest, Cortés arrived. These tensions would foreshadow the great violence of La Noche Triste.

Native tribes, like the Tlaxcaltec, who were daunted by Montezuma’s rule welcomed Cortés when the conquistador explained to those local leaders that his main target was the Aztecs. The smaller tribes readily supplied Cortés with troops and guides to get them as close to Tenochtitlan as possible. When the Spanish arrived at the Aztec metropolis, they were awestruck by the pyramids, great palaces, and the astounding variety of food and luxuries.

Bernal Diaz, a member of Cortés’ army, wrote of the city, “With such wonderful sights to gaze on we did not know what to say, or if this was real that we saw before our eyes”.

What Cortés didn’t know was that Montezuma II would also welcome him. Coincidentally, the Aztec religion spoke of a prophecy regarding the return of the great god Quetzalcoatl, one of the main deities in the Aztec pantheon, in 1519. Montezuma II believed Cortés was one of Quetzalcoatl’s heralds. He allowed Cortés, his Spanish troops, and 1,000 Tlaxcaltec warriors into the capital without a fight.

Wikimedia Commons The Fall of Tenochtitlan as depicted from the Aztec perspective.

Cortés kidnapped Montezuma II in order to rule the Aztecs from behind the scenes. The Spanish proceeded to plunder the Aztec’s treasury of gold, which they planned to take back with them to Spain.

This was the situation until the spring of 1520 when Cortés heard of another Spanish expedition which was to land on the eastern shore of Mexico. Governor Velázquez wanted the men Cortés had unlawfully taken with him to return, so he sent a large party of Spaniards to remove the rogue conquistador by force.

Cortés left some troops to guard Montezuma in the Aztec capital while with others he went to confront his opponents. His men not only defeated the incoming army but the crafty conquistador enlisted them under his own command. However, when he returned to Tenochtitlan in late June 1520, Cortés found the men he left behind under attack.

The commander he left in charge, Pedro de Alvaredo, had led an attack on the Aztec festival of Tóxcatl — for reasons which remain hazy. His troops — combined with the Tlaxcalan warriors — killed thousands of Aztecs in attendance.

Aztecs who had remained loyal to their leadership didn’t take the slaughter lightly. They surrounded the Spanish troops in a sure sign of revolt. Cortés couldn’t calm the masses when he returned to Tenochtitlan as they had lost faith in their previous ruler and his Kidnapping no longer made a difference.

Wikimedia Commons A painting of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire.

La Noche Triste Ensues

The Aztecs had raised all of the bridges surrounding Tenochtitlan in order to trap the Spaniards in the center of the city and food and water began to run dangerously low. Cortés reasoned that the only way out was to construct a mobile bridge and escape under cover of darkness via the Tacuba Causeway.

On the night of La Noche Triste, Cortés ordered his men to carry as much gold as possible, load up the horses, and form a vanguard to protect the cargo.

Díaz del Castillo, one of the survivors of the expedition, wrote that 400 Native Tlaxcalans and 150 soldiers carried the bridge and placed it in position. They then guarded it until all the army and baggage had crossed safely. Other soldiers and Tlaxcalans were armed.

But the Spaniards were caught and a massacre of their troops ensued.

Many soldiers drowned in Lake Texcoco. Montezuma was also killed, though reports contradict each other as to whether he was killed by the Spanish or killed by the Aztecs — who felt betrayed by his European allegiance.

Cortés estimated that he lost most of his soldiers that night, though he himself was lucky to have escaped.

Wikimedia Commons A painting called The Conquest of Tenochtitlan. Cortés didn’t like losing the first time around.

But the conquistador wanted revenge for La Noche Triste and he planned it for nearly a year.

in 1521, Cortés took enough men with him to conquer the Aztecs and lay waste to Tenochtitlan. This final siege would mark the fall of the Aztec empire. Cortés took up more gold and returned to Spain with it as the Aztec empire turned to rubble.

Indeed, La Noche Triste was more a sad chapter in Aztec history than in Spanish history. Though for a brief moment the natives had successfully staved off their conquerors in this battle, the Spaniards would win the war and thus hasten the decimation of native Mesoamerican tribes in the process.

The overall disappearance of the Aztecs in the 1540s, however, might not have been due to a mysterious plague as was once believed, but rather a deadly bout of Salmonella that likely came from the foreign Europeans.

After learning about La Noche Triste, read more on the Aztecs with this article on which deadly Aztec weapon was most feared by the Spaniards and the Aztecs’ enemies. Then, check out the sad tale of Charles II, the Spanish king so ugly he scared even his wife.