Known informally as the Japanese mafia, the Yakuza are a 400-year-old criminal syndicate that carries out everything from human trafficking to real estate sales.

When news broke that the Yakuza were among the first on the scene after Japan’s devastating 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, it caused a minor sensation in Western media outlets, which tended to view the Yakuza as the Japanese mafia, more akin to John Gotti than to Jimmy Carter.

But that notion of the Yakuza gets it all wrong. The Yakuza were never just some Japanese gangsters, or even a single criminal organization.

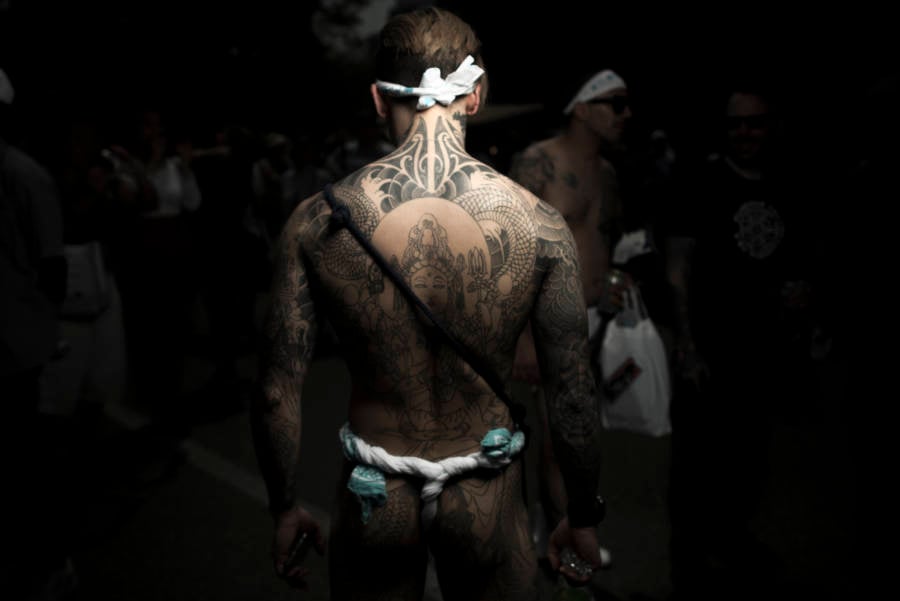

Kan Phongjaroenwit/FlickrThree members of the Yakuza show off their full-body tattoos in Tokyo. 2016.

The Yakuza were, and remain today, something else altogether – a complex group of syndicates and the country’s most powerful and misunderstood criminal gangs.

And they are inexorably tied to 400 years of Japanese and Yakuza history. The Yakuza, it turns out, aren’t what you think.

The Ninkyo Code And Humanitarian Aid

Wikimedia CommonsThe damage after the Tohoku Earthquake. The Yakuza were among the first to organize relief efforts for the survivors. March 15, 2011.

In the spring of 2011, Japan was devastated by one of the most brutal tsunamis and earthquakes in the country’s history. The people of the Tōhoku region saw their homes torn to shreds, their neighborhoods shattered, and everything they knew lost.

But then help arrived. A fleet of more than 70 trucks poured into the towns and cities of Tōhoku, filled with food, water, blankets, and everything residents could possibly hope for to stitch their lives back together.

But those first trucks didn’t come from their government. The first relief teams to arrive, in many parts of Tōhoku, came from another group that most people don’t associate with good deeds.

They were members of the Japanese Yakuza, and it wasn’t the only time in Yakuza history that they had come to the rescue.

Colin and Sarah Northway/FlickrYakuza during the Sanja Matsuri festival, the only time of the year that they are allowed to show their tattoos.

After 1995’s Kobe earthquake, the Yakuza had also been the first on the scene. And not long after their 2011 Tōhoku relief effort started winding down, the Yakuza sent men into the deadly Fukushima nuclear reactor to help alleviate the situation resulting from the meltdown that had been caused by the tsunami as well.

The Yakuza — a term that refers to both the various gangs and the members of those gangs — help out in times of crisis because of something called the “Ninkyo Code.” It’s a principle every Yakuza claims to live by, one that forbids them to allow anyone else to suffer.

At least, that’s what Manabu Miyazaki, an author who has written more than 100 books about the Yakuza and minority groups, believes. The charitable arm of organized crime, he believes, is rooted in Yakuza history. As he puts it, “Yakuza are dropouts from society. They’ve suffered, and they’re just trying to help other people who are in trouble.”

The secret to understanding the Yakuza, Miyazaki believes, lies in their past — one that stretches back to the 17th century.

How The Yakuza Began With Japan’s Social Outcasts

Yoshitoshi/Wikimedia CommonsAn early Japanese gangster cleans the blood off of his body.

Japanese Yakuza history begins with class. The first Yakuza were members of a social caste called the Burakumin. They were the lowest wretches of humanity, a social group so far below the rest of society that they weren’t even allowed to touch other human beings.

The Burakumin were the executioners, the butchers, the undertakers, and the leather workers. They were those who worked with death – men who, in Buddhist and Shinto society, were considered unclean.

The forced isolation of the Burakumin had started in the 11th century, but it got far worse in the year 1603. That year, formal laws were written to cast the Burakumin out of society. Their children were denied an education, and many of them were sent out of the cities and forced to live in secluded towns of their own.

Today, things aren’t as different as we’d like to think. There are still lists passed around Japan that name every descendant of a Burakumin and are used to bar them from certain jobs.

And to this day, the names on those lists reportedly still make up more than half of the Yakuza.

Utagawa Kunisada/Wikimedia CommonsBanzuiin Chōbei, an early gang leader who lived in 17th-century Japan, under attack.

The sons of the Burakumin had to find a way to survive despite the few options available to them. They could carry on their parents’ trades, working with the dead and ostracizing themselves further and further from society — or they could turn to crime.

Thus, crime flourished after 1603. Stalls peddling stolen goods started cropping up around Japan, most run by sons of Burakumin, desperate to earn enough income to eat. Meanwhile, others set up illegal gambling houses in abandoned temples and shrines.

Wikimedia CommonsA member of the Yakuza inside of an illegal Toba casino. 1949.

Soon – nobody’s exactly sure when – the peddlers and gamblers started setting up their own organized gangs. The gangs would then guard other peddlers’ shops, keeping them safe in exchange for protection money. And in those groups, the first Yakuza were born.

It was more than just profitable. It won them respect. The leaders of those gangs were officially recognized by Japan’s rulers, given the honor of having surnames, and allowed to carry swords.

At this point in Japanese and Yakuza history, this was deeply significant. It meant that these men were being granted the same honors as nobility. Ironically, turning to crime had given the Burakumin their first taste of respect.

They weren’t going to let that go.

Why The Yakuza Are More Than The Japanese Mafia

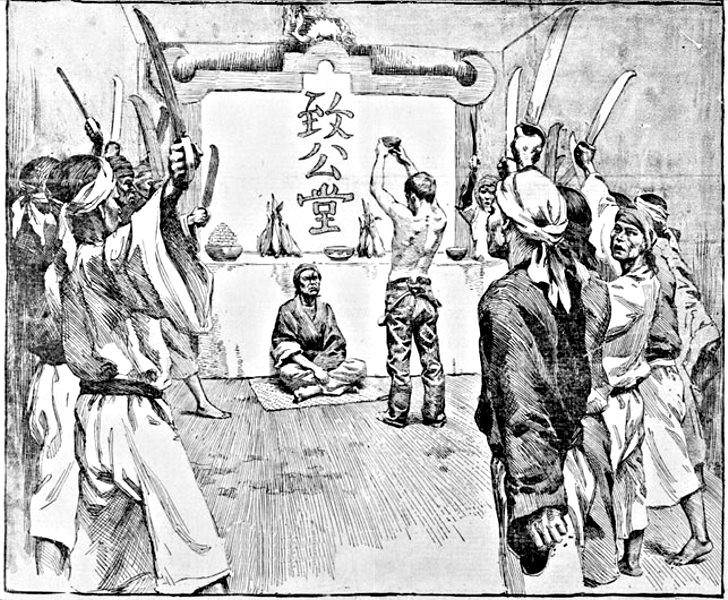

Schreibwerkzeug/Wikimedia CommonsA traditional Yakuza initiation ceremony.

It didn’t take long before the Japanese Yakuza was a full-blown group of criminal organizations, complete with their own customs and codes. Members are meant to observe strict codes of loyalty, silence, and obedience — codes that have remained throughout Yakuza history.

With these codes in place, the Yakuza were like family. It was more than just a gang. When a new member came in, he accepted his boss as his new father. Over a ceremonial glass of sake, he would formally accept the Yakuza as his new home.

FRED DUFOUR/AFP/Getty ImagesYakuza tattoos on display during the 2017 Sanja Matsuri festival in Tokyo.

Loyalty to the Yakuza had to be complete. In some groups, a new Japanese gangster would even be expected to completely cut ties with his biological family.

To the men who joined these gangs, though, this was part of the appeal. They were social outcasts, people who had no connection in any part of society. The Yakuza, to them, meant finding a family in the world, finding people you could call your brothers.

Tattoos And Rituals Of A Yakuza Member

Armapedia/YouTubeThe hands of a Yakuza with the left pinky sliced off.

Part of what signifies Japanese Yakuza members’ loyalty is how they will change their very appearance. New Yakuza members would cover themselves from head to toe in elaborate, complex tattoos (in the traditional Japanese style known as irezumi), slowly and painfully etched onto the body with a sharpened piece of bamboo. Every part of the body would be marked.

Eventually, it would become forbidden for Yakuza to show off their tattoo-covered skin. Even then, though, it wasn’t hard to spot a Japanese gangster. There was another way to tell: the missing finger on their left hands.

BEHROUZ MEHRI/AFP/Getty ImagesYakuza participate in the 2018 Sanja Matsuri festival in Tokyo.

In Yakuza history, this was the standard punishment for disloyalty. Any Japanese gangster who disgraced the Yakuza name would be forced to cut off the tip of the left pinky and hand it over to the boss.

In the early days, it had a practical purpose. Every cut to a finger would weaken a man’s sword grip. With every offense, the man’s abilities as a warrior would diminish, pushing him to be more and more reliant on the protection of the group.

A History With The Drug Trade And Sexual Slavery

Jiangang Wang/Contributor/Getty ImagesYakuza display their tattoos during the the Sanja Matsuri festival in Tokyo. 2005.

Historically, the Japanese Yakuza have largely carried out what many would consider to be relatively small-time crimes: drug dealing, prostitution, and extortion.

The drug trade, in particular, has proven extremely important to the Yakuza. To this day, nearly every illegal drug in Japan is imported by the Yakuza.

Among the most popular is meth, but they also bring in a steady stream of marijuana, MDMA, ketamine, and anything else they think people will buy. Drugs, as one Yakuza boss put it, are just plain profitable: “One sure way of making money is drugs: that’s the one thing you can’t get hold of without an underworld connection.”

Darnell Craig Harris/FlickrA woman walks out of a brothel in Tokyo.

But drugs isn’t all that the Yakuza import. They also traffic in women. Yakuza operatives travel to South America, Eastern Europe, and the Philippines and lure young girls to Japan, promising them lucrative jobs and exciting careers.

When the girls get there, though, they find out that there is no job. Instead, they’re trapped in a foreign country and without enough money to go home. All they have is the Japanese gangster they have been set up with – a man pushing them into a life of prostitution.

The brothels themselves are usually massage parlors, karaoke bars, or love hotels, often owned by somebody who isn’t in the gang. He’s their civilian front, a fake boss extorted into letting them use his business and the guy who’ll take the fall if the police come calling.

All that’s true today, as it has been for years. But none of it is what eventually caused the government to truly crack down on the Yakuza.

The crackdown came when the Yakuza moved into white-collar crime.

How They Started “Legitimate” Real Estate

FRED DUFOUR/AFP/Getty ImagesYakuza display their tattoos during the Sanja Matsuri festival in Tokyo. 2017.

Up until recently, the Japanese Yakuza have been at least somewhat tolerated. They were criminals, but they were useful – and sometimes, even the government took advantage of their unique skills.

The Japanese government has called on them for help in military operations (though the details remain hazy), and in 1960, when President Eisenhower visited Japan, the government had him flanked by scores of Yakuza bodyguards.

While things like this have made the Yakuza at least look more legitimate, their code also forbids members from stealing – even if, in practice, that rule wasn’t always followed. Nevertheless, many members throughout Yakuza history saw themselves simply as businessmen.

Wikimedia CommonsDemolition work in Japan. 2016.

Real estate was one of the Yakuza’s first big white-collar scams. In the 1980s, the Yakuza started sending their enforcers off to work for real estate agents.

They were called the Jigeya. Real estate agents would hire a Japanese gangster when they wanted to demolish a residential area and put in a new development, but couldn’t get one stingy landowner to leave.

The Jigeya’s job was to get them out. They’d put unpleasant things in their mailboxes, scrawl obscene words on their walls, or – in at least one case – empty the contents of an entire septic tank in through their window.

Whatever it took to get someone to sell, the Yakuza would do it. They did the dirty work – and, according to Yakuza member Ryuma Suzuki, the government let them do it.

“Without them, cities wouldn’t be able to develop,” he said. “The big corporations don’t want to put their hands into the dirt. They don’t want to get involved in trouble. They wait for other companies to do the dirty business first.”

Publicly, the Japanese government has washed their hands of them – but Suzuki might not be entirely wrong. More than once, the government itself has been caught hiring the Yakuza to muscle people out of their homes.

The Yakuza Enter The Business World

Secret Wars/YouTubeKenichi Shinoda, a Japanese gangster and leader of the Yamaguchi-Gumi, the largest of the Yakuza gangs.

After getting into real estate development, the Japanese Yakuza moved into the business world.

Early on, the Yakuza’s role in white-collar crime was mostly through something call Sōkaiya – their system for extorting businesses. They would buy enough stock in a company to send their men to stockholder meetings, and there they would terrify and blackmail companies into doing whatever they wanted.

And many companies invited the Yakuza in. They came to the Yakuza begging for massive loans that no bank would offer. In exchange, they’d let the Yakuza take a controlling stake in a legitimate corporation.

The impact has been huge. At their peak, there were 50 registered companies listed on the Osaka Security Exchange that had deep ties to organized crime. It was arguably the golden era in Yakuza history.

EthanChiang/FlickrA Yakuza member stands on a crowded street. 2011.

Legitimate business, the Yakuza quickly learned, was even more profitable than crime. They started setting up a stock investment plan – they would pay homeless people for their identities and then use them to invest in stocks.

They called their stock investments rooms “dealing rooms,” and they were incredibly profitable. It was a whole new era – a whole new breed of crime for the Yakuza of the 1980s. As one Japanese gangster put it:

“I once did time in jail for trying to shoot a guy. I’d be crazy to do that today. There’s no need to take that kind of risk anymore,” he said. “I’ve got a whole team behind me now: guys who used to be bankers and accountants, real estate experts, commercial money lenders, different kinds of finance people.”

The Fall Of The Yakuza

Wikimedia CommonsThe Kabukicho district of Shinjuku, Tokyo.

And as they made deeper inroads into the world of legitimate business, the days of Yakuza violence were waning. Yakuza-related murders – one Japanese gangster killing another – were cut in half in a few short years. Now it was white-collar, almost-legal business – and the government hated that more than anything.

The first so-called “anti-Yakuza” law was passed in 1991. It made it illegal for a Japanese gangster to even get involved in some types of legitimate business.

Since then, the anti-Yakuza laws have piled on. Laws have been set up barring how they can move their money; petitions have been sent to other countries, begging to freeze Yakuza assets.

And it’s working. The Yakuza’s memberships are reportedly at an all-time low in recent years – and it’s not just because of arrests. For the first time, they are actually starting to let gang members go. With their assets at least partially frozen, the Yakuza just don’t have enough money to pay their members’ wages.

A Criminal Public Relations Campaign

Mundanematt/YouTubeThe Yakuza open up their headquarters once each year to hand out candy to children.

All that pressure just might be the real reason why the Yakuza have become so generous.

The Yakuza wasn’t always involved in humanitarian efforts. Like the police crackdown, their good deeds didn’t really start until they moved into white-collar crime.

Journalist Tomohiko Suzuki doesn’t agree with Manabu Miyazaki. He doesn’t think the Yakuza are helping out because they understand how hard it can be to feel left out. He thinks it’s all a big PR stunt:

“The Yakuza are trying to position themselves to gain contracts for their construction companies for the massive rebuilding that will come,” Suzuki said. “If they help citizens, it’s hard for the police to say anything bad.”

IAEA Imagebank/FlickrA team of relief workers at the Fukushima Reactor. 2013.

Even as humanitarians, their methods aren’t always entirely above-board. When they sent help to the Fukushima reactor, they didn’t send their best men. They sent homeless people and people who owed them money.

They would lie to them about what they would be paid, or threaten them with violence to help out. As one man who was tricked into working there explained:

“We were given no insurance for health risks, no radiation meters even. We were treated like nothing, like disposable people – they promised things and then kicked us out when we received a large radiation dose.”

But the Yakuza insist they’re just doing their best and honoring Yakuza history. They know what it’s like to be abandoned, they say. They’re just using what they have to make things better.

As one Japanese mafia member says, “Our honest sentiment right now is to be of some use to people.”

After this look at the Yakuza, the Japanese mafia, discover the widely misunderstood history of the geisha. Then, read about the appalling torture and murder of Junko Furuta, whose primary attacker’s Yakuza connections helped him carry out the crime.