Discover the 12,000-year history of irezumi, the ancient form of Japanese body art widely seen as a Yakuza tattoo tradition today.

For three days a year on the third weekend of May, the streets of Tokyo's Asakusa district come alive. A great procession of men stripped to their underwear flood the streets and show off the tapestry of colors painted onto their skin thanks to the ancient Japanese tattoo art of irezumi.

It is the Sanja Matsuri festival: the one time of year when the men of Japan’s Yakuza crime syndicates will tear off their clothes and reveal the full-body tattoos that, in the minds of many, are the very thing that mark them as criminals.

To the police watching from the sidelines, it can seem an unnerving display of strength. A whole crowd of people is there, cheering on criminals, brazenly showing off their irezumi — now commonly thought of as a Yakuza tattoo tradition.

But an irezumi isn't just a Yakuza tattoo, it's the mark of a complex Japanese tradition that has been a part of the nation’s history for some 12,000 years.

12,000 Years Of Irezumi Tattoos

The earliest hints of tattoos in Japan come from the remains of people who died in the Paleolithic period. Already, back in 10,000 B.C., the people of Japan were marking their bodies with ink.

And across 12,000 years of history since, tattoos have been a part of Japanese life. The styles, the meanings, and the purposes may have changed, but tattoos have always been there since the beginning.

In fact, the earliest written reference to Japan, made by a Chinese explorer in 300 B.C., talked about the people's tattoos:

“The men of Wa (Japan) tattoo their faces and paint their bodies with designs. They are fond of diving for fish and shells. Long ago they decorated their bodies in order to protect themselves from large fish and later these designs became ornamental.

Body painting differs among the various tribes with the position and size of the designs vary according to the rank of individuals; they smear their bodies with pink and scarlet just as Chinese use powder.”

And for the very first indigenous people of modern-day Japan — the Ainu of Hokkaido, a group believed to have coalesced in the 13th century — tattoos were a way to ward off evil spirits. Women would get their lips marked with patterns of ink, convinced it would keep them safe at night.

Irezumi was a part of their culture, a part of their pride. In those days, unlike at Sanja Matsuri today, there was no sense that a tattooed person was a criminal.

The Edo Period

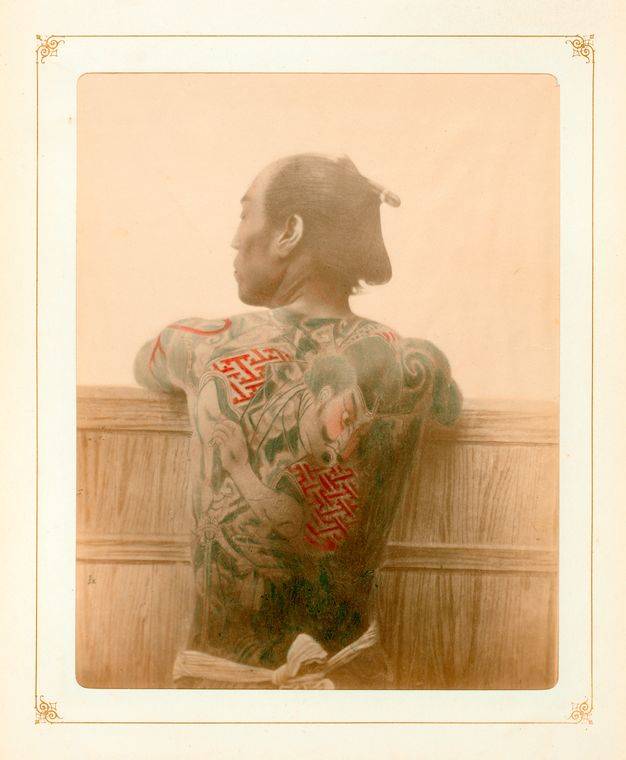

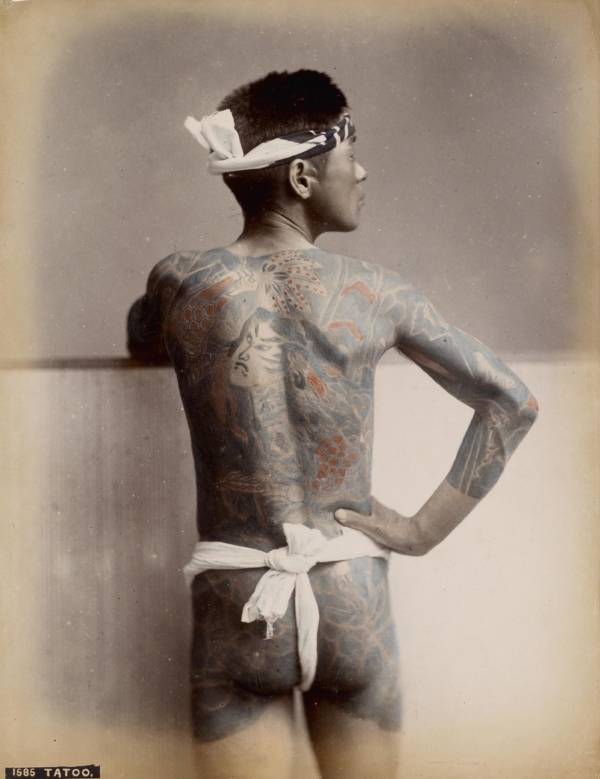

During what's known as the Edo period in Japanese history (roughly 1600-1868), irezumi underwent a revolution. Woodblock printers moved into the world of body art, developing an art form that was uniquely Japanese.

People began covering their whole bodies in incredibly complex, ornate, and colorful tattoos. Scenes of flowers and dragons would cover their backs and stretch down their arms, turning human beings into living canvases.

In part, the revolution was brought on by the classic Chinese story known as Water Margin, attributed to 14th-century author Shi Nai'an. The novel, centered around the adventures of a band of heroic outlaws, became a sensation in Edo Japan, and woodblock artists rushed to turn the scenes of the novel into works of art.

More often than not, these artists would depict the heroes coated in tattoos, covered with such intricate and powerful designs that, even when stripped bare, their bodies were infused with color.

The public loved the artwork, turning woodblock artists like Utagawa Kuniyoshi into such celebrities that their art is still displayed today. But the people didn’t just want such art on their walls. Like the heroes of the novel, they wanted the art etched into their skin.

Soon, it seemed as though everyone with the means and the courage (specifically men and especially firefighters, who wore them for their supposed sex appeal and spiritual protection) to get themselves tattooed sported irezumi with elaborate designs like those of their favorite literary heroes.

The Yakuza Tattoo Tradition

All of this changed, though, in the Meiji Period at the turn of the 20th century. The Japanese government, wanting their country to appear dignified and respectable as they first became open to Westernization, outlawed tattoos. Irezumi thus became associated with criminals — especially the Yakuza.

Now, this wasn’t the first time that irezumi had marked dangerous men. In the fifth century A.D., the Japanese government had used tattoos as a way to punish criminals.

A first offense would earn a man a line across his forehead. A second would add an arch. And if he committed a third, a final line would be added, forming the Japanese character for “dog”.

But then, only one, specific tattoo was associated with criminals. The Meiji change was different: Now every tattoo of any kind was a sign that someone was up to no good.

Eventually, the law changed again at the end of World War II and tattoos became legal once more. But the idea that irezumi was an outlaw Yakuza tattoo tradition lived on. To this day, many businesses still ban customers with ink on their skin.

Nevertheless, the irezumi art form is alive and well, though it is widely seen as either a Western obsession or a Yakuza tattoo tradition.

Still, for three days each year, when the Sanja Matsuri festival comes around, those tattoos take over the streets, giving the world a little glimpse into the Japan that once was.

After this look at the Yakuza tattoo art of irezumi, learn all about the misunderstood history of the geisha. Then, discover everything there is to know about the samurai suicide ritual of seppuku.