The summerless year of 1816 came after the eruption of Mount Tambora, the Indonesian volcano that violently exploded in April 1815 and sent clouds of ash into the atmosphere that blocked sunlight and caused global temperatures to drop.

Public DomainTwo Men by the Sea (1817), a painting by Caspar David Friedrich that shows the dark, dreary skies that followed Mount Tambora’s eruption.

On April 10, 1815, Mount Tambora erupted in what would become the most powerful volcanic blast in recorded human history. In the immediate aftermath of the eruption, the volcano shot massive amounts of gas, dust, and rock into the atmosphere. All of that debris ultimately led to the globally devastating “Year Without a Summer.”

The particles lingering in the stratosphere blocked solar radiation and absorbed heat, creating extreme weather conditions, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere. So, when summer rolled around in 1816, the usual warmth did not accompany it. Instead, the world fell into a cold volcanic winter.

Crops did not grow, leading to food scarcity and famine. Europe was still dealing with the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, and the bitter chill and subsequent crop failures led to civil unrest across the continent. American farmers, meanwhile, saw a mass westward migration to seek more suitable farmland.

There were other, more positive outcomes from the Year Without a Summer, though, specifically in the fields of art and literature. At the very least, we have that turbulent period to thank for Frankenstein.

How Mount Tambora’s Eruption Caused The ‘Year Without A Summer’ Of 1816

For many, the Year Without a Summer seemed like a random, terrible event with no immediate cause. After all, even if someone had heard Mount Tambora erupt — and many people did, even from hundreds of miles away — they couldn’t have known that it would cause a global climate crisis.

There were some other factors that contributed to the frigid winter. According to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, Earth was nearing the end of the Little Ice Age at the time, so temperatures were already down across the planet. Mount Tambora’s eruption, however, pushed things way past the tipping point.

NASAMount Tambora in the modern day, more than 200 years after its massive eruption of 1815.

The dust and debris spewed into the atmosphere created a “great cosmic umbrella,” effectively limiting the amount of sunlight that reached Earth’s surface. People noticed it at the time, too.

“There are so many reports from those years, 1816 and 1817, that the sunlight was sort of dim,” Gillen D’Arcy Wood, an English and environmental humanities professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told The Collector in 2024. “As if someone had turned the dimmer light down on the planet. And then there were all these crazy weather anomalies.”

Indeed, while small changes in temperature may have been easy to write off, snow in June wasn’t so easy to ignore.

Extreme Weather Events Destroyed America’s Crops

1816 may have been the Year Without a Summer, but even before the summer months, it was clear that something wasn’t right.

As farmers were getting ready to sow crops in the springtime, they found that the cold weather had not let up. Even as late as May, frosts killed off most crops in places like upstate New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. That wasn’t all, though.

In June — typically, one of the hotter months in the Northern Hemisphere — Albany, New York, saw snowfall. Later that month, Cape May, New Jersey, reported five nights in a row of frost that destroyed crops. In late July and August, river ice was seen in parts of northwestern Pennsylvania, and frost was still impacting farms as far south as Virginia.

“What would happen if the Sun should become tired of illuminating this gloomy planet?” one writer for the North American Review asked at the time.

National ArchivesThe Year Without a Summer helped spark the westward migration that would define 19th-century America.

American farmers struggled to keep their crops alive, and the scarcity raised the prices of grain and oats exponentially. This also impacted transportation and shipping costs, as horses relied on oats to fuel them during long journeys. Many farmers in New England left their properties and headed westward, hoping to find more suitable land to grow crops. This was understandable, given that at least one farmer in Vermont froze to death.

As recounted by his nephew, James Winchester:

“I was at my uncle’s when he left home to go to the sheep lot, and as he went out the door, he said, jokingly, to his wife: ‘If I am not back in an hour, call the neighbors and start them after me. June is a bad month to get buried in the snow, especially when it gets so near July.’ … Three days later, searchers found him… frozen stiff.”

Across the pond, things weren’t looking any better.

Europe And Asia Faced Famine, Floods, And Disease

Ireland, in particular, experienced a great famine during the Year Without a Summer, as farmers were unable to grow enough potatoes, wheat, and oats to sustain the population.

Other parts of Europe also experienced food scarcity. And when people are cold, the skies are bleak, and there’s nothing to eat, unrest tends to break out. Riots, arson, and looting were frequent across European cities, which were still reeling from the fallout of the Napoleonic Wars. A massive outbreak of typhus added to the misery.

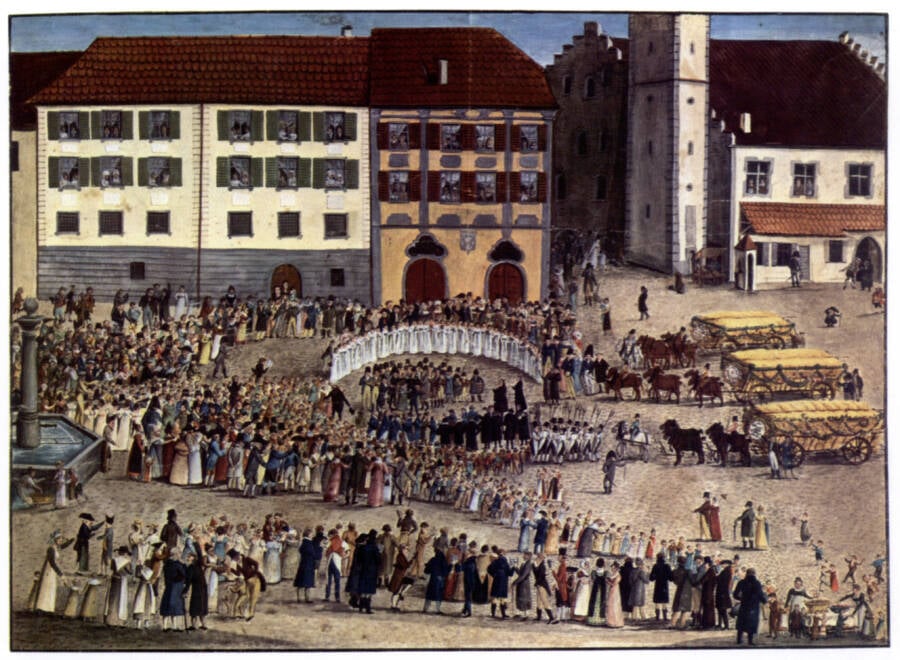

Public DomainWagons enter the German town of Ravensburg in 1817 carrying the first harvest following the Year Without a Summer.

Meanwhile, Asia was wracked by catastrophic flooding due to the disruption of the monsoon season, which also led to deadly famine.

The Chinese poet Li Yuyang documented the devastation in his Poetry of the Seven Sorrows, particularly in the Yunnan province, which had previously been prosperous thanks to its agriculture and mining industries. From 1816 onward, however, three years of record-low temperatures, heavy rainfall, and flooding decimated crops — even rice, which is generally a hardier plant.

Li Yuyang’s poetry was a bleak representation of the everyday horrors people faced that summer and in the subsequent years, but he was not the only artistic or literary figure to pull from his experience of the time.

How The Year Without A Summer Affected Art

Although cameras were not yet commonplace in 1816 — the first photograph would not be taken for another decade — there are still artistic depictions of the dreary sky from that period. In fact, the Year Without a Summer had a profound impact on art.

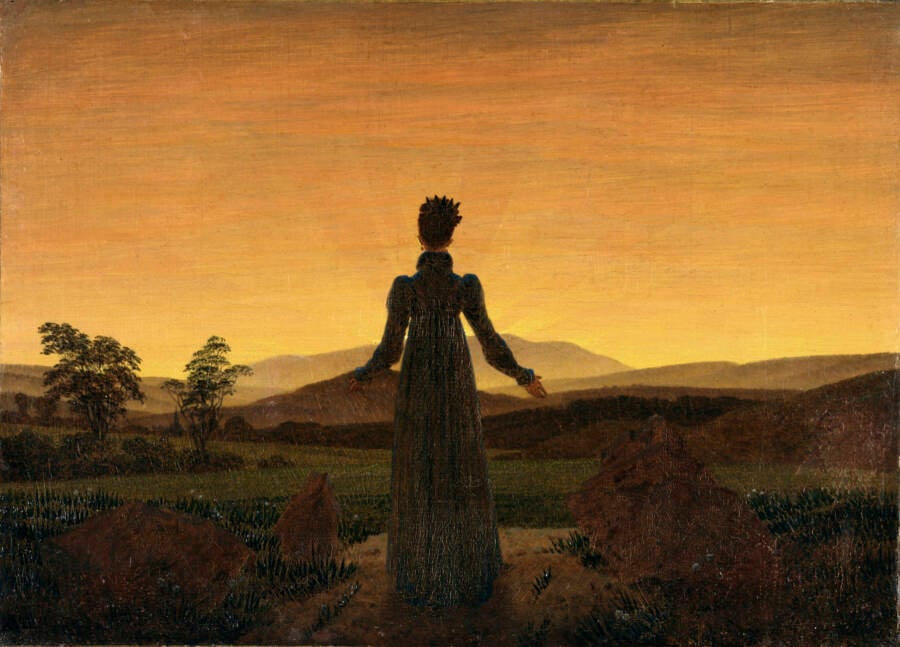

Public DomainWoman Before the Rising Sun (1818), a Caspar David Friedrich painting showing the yellow-tinged sky that followed Mount Tambora’s eruption.

One of the most famous paintings from this period, Caspar David Friedrich’s Woman Before the Rising Sun, shows a silhouetted woman standing in front of a sky often described as “apocalyptic.” Whether he knew it or not, Friedrich had captured a genuine scientific marvel: the volcanic fallout from Mount Tambora’s eruption. Two of Friedrich’s other works, The Monk by the Sea and Two Men by the Sea, also show this shift in the sky.

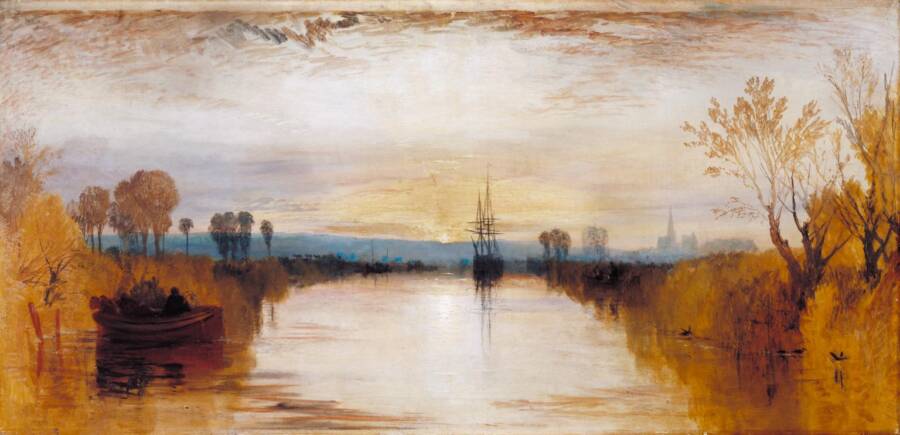

A similar pattern appeared in the work of painter J. M. W. Turner, whose post-eruption works featured a predominant yellow tinge, likely caused by high levels of tephra — rock fragments in the atmosphere after a volcanic eruption — in the atmosphere even a decade later.

Public DomainChichester Canal, painted by J. M. W. Turner in 1828, also features a yellow sky.

Similar shifts occurred after the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991.

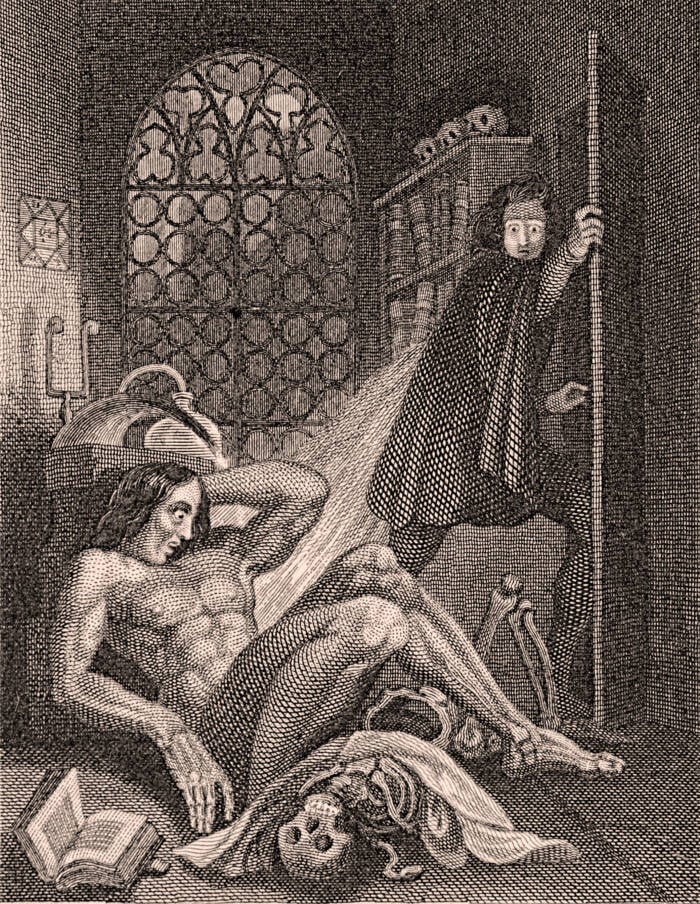

The Year Without a Summer also gave us one of the most influential literary works in history: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. As the story goes, Shelley and her husband, Percy, were vacationing with the poet Lord Byron and several other friends in Switzerland during the cold summer. The dismal weather forced them to remain indoors, where they smoked opium and engaged in conversation, which eventually resulted in a writing competition — one that resulted in the creation of Frankenstein.

Public DomainThe frontispiece of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

Looking back, it’s easy to see why the conditions during the Year Without a Summer would inspire such horrors. People were dying en masse, starving in the streets, unable to grow crops, and freezing when it was meant to be warm. The rain was constant and heavy, and the land was covered in fog.

Many nights in 1816 were, as the horror cliché goes, “dark and stormy.”

After reading about why 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer, learn all about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and how it destroyed the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Then, discover the story of Robert Landsburg, the photographer who spent his final moments documenting the eruption of Mount St. Helens.