From 1866 to 1868, Sioux Chief Red Cloud successfully fought the expansion of white settlers into Oglala Lakota territory in Wyoming, Montana, and South Dakota.

Library of CongressChief Red Cloud is the most photographed Native American of the 19th century.

Something unusual happened in 1868. After trying to bend Native Americans in the Great Plains to their will, the U.S. government instead gave up, sued for peace, and conceded to their demands. This remarkable victory was due to Chief Red Cloud.

A Sioux leader, Red Cloud had watched with dismay as white settlers marched through his people’s land in search of gold. For two years, he resisted the U.S. government at every turn in what came to be known as Red Cloud’s War.

He succeeded in expelling U.S. troops, blocking white settlers, and securing tribal lands. But even though Chief Red Cloud won significant concessions from the government, it didn’t take long for the U.S. to renege on its promises.

The Making Of A Lakota Warrior

Born in 1822, Chief Red Cloud — Maȟpíya Lúta — seemed marked for great things. He grew up near the Platte River in western Nebraska, the son of a Brule Sioux father and an Oglala Sioux mother. Because his parents died when he was young, he was raised by his maternal uncle, Old Smoke.

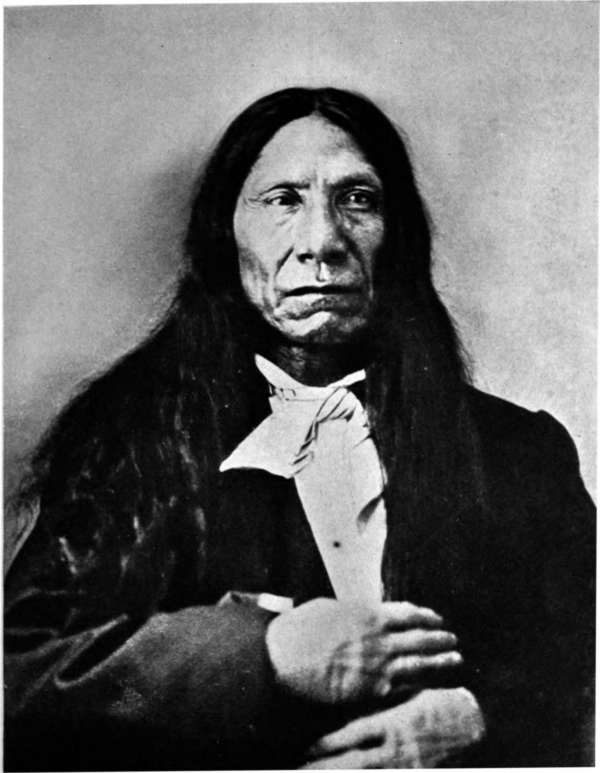

Wikimedia CommonsA photo of Red Cloud taken circa 1872. In his life, more than 100 photos were taken of him.

As a young man, Red Cloud proved himself as a fierce warrior. During battles his people fought with Pawnee, Crow, Ute, and Shoshone tribes, Red Cloud racked up 80 “coups,” or feats of bravery. On one occasion, he saved a Ute man from drowning, only to kill him and scalp him on the shore.

He also proved himself an able tactician. He developed a strategy of deploying small war parties of eight to 12 men, whom he always commanded. By the time he was 28, he enjoyed the respect and admiration of most of his tribe.

But Red Cloud’s ascendency dovetailed with a surge in white settlers who poured west in the aftermath of the California Gold Rush in 1848. As the settlers clashed with native tribes, the U.S. government sat both sides down to hammer out a treaty.

The resulting Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 (also called the Horse Creek Treaty) promised to protect tribal lands and hunting grounds against white settlement. But as eager settlers poured west, the U.S. government did little to stop them.

The Bozeman Trail And Red Cloud’s War

By 1864, tensions between Native Americans and settlers had intensified. The discovery of gold in southwestern Montana led to the construction of the Bozeman Trail, a road that ran straight through Lakota territory. Soon, the government built forts to protect settlers and prospectors.

This, combined with the Sand Creek massacre when U.S. troops killed hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho people — convinced Red Cloud that he needed to act.

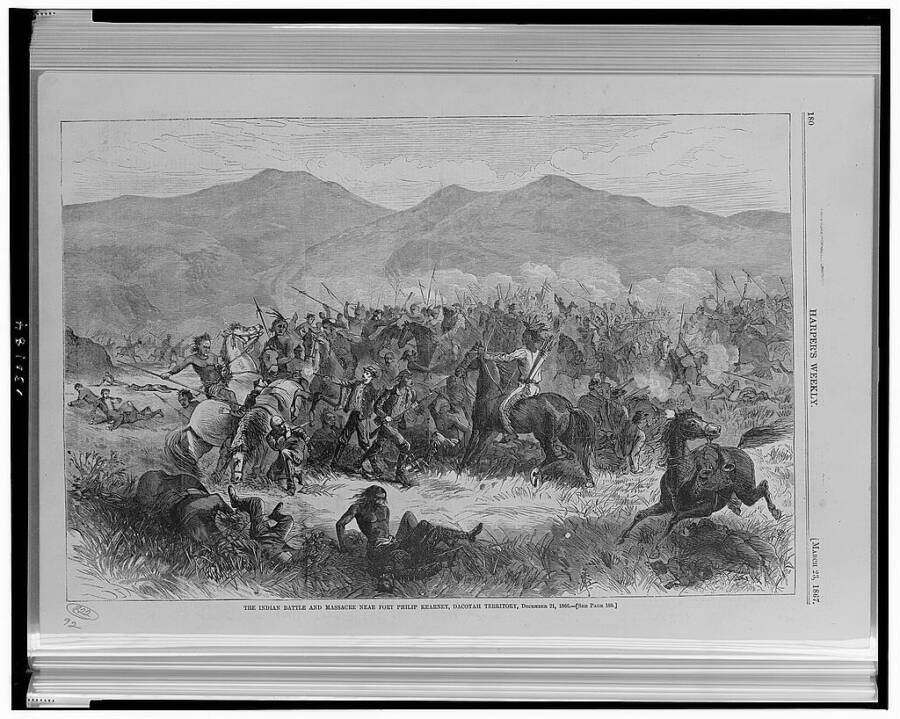

Library of CongressA Harper’s Weekly depiction of the Fetterman Massacre, also called the Battle of the Hundred Slain.

Between 1866 and 1868, the determined warrior gathered a coalition of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors and fought back. Refusing to negotiate with the government, he instead launched guerilla-style attacks on settlers and the forts themselves. They targeted wagon trains, blocked the trail, and laid siege to the forts.

At the end of 1866, a newly-arrived U.S. Army captain named William Fetterman set out to squash the Native Americans’ resistance. Boasting that “with 80 men, I could ride through the whole Sioux Nation,” Fetterman led his troops straight into an ambush.

Facing 2,000 Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, Fetterman and his men were killed. It was the U.S. Army’s worst defeat in the Great Plains up to that point and convinced many American policymakers to try and negotiate with Red Cloud. But he wouldn’t budge an inch until the army abandoned its Bozeman Trail forts.

Finally, by 1868, the government relented. In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the U.S. promised to abandon its forts. The government also conceded a large swath of territory encompassing parts of Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana. As U.S. troops left, Red Cloud’s warriors burned the forts to the ground.

However, though Red Cloud’s War ended in a victory for the tribes, it wasn’t exactly a defeat for the U.S. government. The transcontinental railroad, which was completed in 1869, made the Bozeman Trail obsolete. And while the government had made plenty of promises in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, it kept few of them.

How Chief Red Cloud Fought For Peace

It didn’t take long for the U.S. government to renege on its promises. Forts soon started popping up on Lakota territory again. But whereas many of Chief Red Cloud’s contemporaries waged war, the Lakota leader opted for diplomacy.

In 1870, he made the long trip east to Washington, D.C. There, Chief Red Cloud was treated like a head of state and invited to a White House reception. He met with President Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of the Interior Jacob Cox.

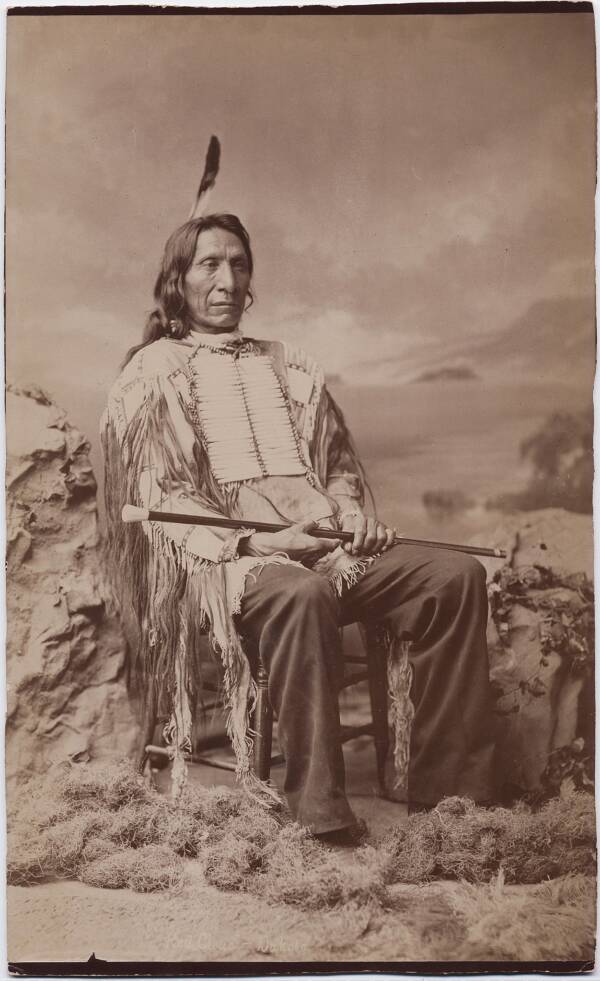

Wikimedia CommonsAfter winning Red Cloud’s War, Chief Red Cloud opted to use diplomacy.

To Cox, Chief Red Cloud condemned the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 as “all lies.” His people were being pushed onto smaller and smaller parcels of land, and white settlers were still flooding the Plains. Red Cloud told him, “We have been driven far enough; we want what we ask for.”

But American westward expansion continued — especially after the discovery of gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1874. Still hoping for peace, however, Red Cloud did not participate in the Lakota War of 1876-77. Nor did he take up arms for the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 (though his son Jack did).

Instead, Red Cloud kept going to the nation’s capital. He spoke to presidents, policymakers, and curious audiences of Americans. He tried to make his case and defend his people.

“Whose voice was first sounded on this land?” Red Cloud demanded during a speech on one such trip. “The red people with bows and arrows. The Great Father [President Grant] says he is good and kind to us. I can’t see it.”

He added, “When the white man comes in my country he leaves a trail of blood behind him.”

However, Red Cloud could do little as settlers relentlessly marched west despite his thunderous defense of his people.

Chief Red Cloud’s Death And Legacy

In the last decades of his life, Chief Red Cloud continued to fight for his people. He visited Washington, D.C., nine times and met with five different presidents over thirty years to advocate for Native American rights.

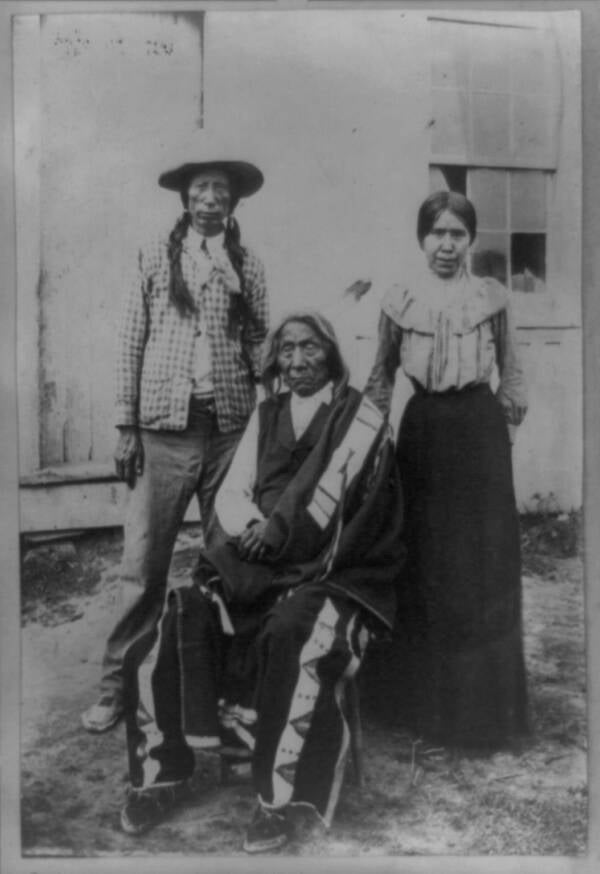

Library of CongressChief Red Cloud in 1909 on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota with his son, Jack Red Cloud, and granddaughter.

During his visits, he frequently sat for photographs. In doing so, Red Cloud became the most photographed Native American of the 19th century, and his portraits offer a stunning look at his dignity, fortitude, determination, and pride.

Of course, he did more than sit for pictures. Significantly, he helped dictate the agreement for his tribe’s territory and determine the bounds of the Pine Ridge Reservation. He moved there with his people in 1878 and stepped down as leader two years later.

Even out of power, however, Red Cloud kept shaping policy. He fought against the Dawes Act, which sought to turn Native Americans into farmers. He invited the Jesuits to start a school on tribal land, thus keeping local children close. And he discouraged the Ghost Dance, a spiritual movement that promised to restore Native Americans’ lands.

Some members of the Lakota grew impatient with him. Certain factions thought that they should resume the “warpath.” Others believed that Red Cloud was slowing down the inevitable march toward accepting “white” customs.

Many even blamed him for the death of Crazy Horse. Red Cloud had encouraged his fellow warrior to turn himself into the U.S. government, and Crazy Horse subsequently had died in their custody.

“I, of course, as many others have done before me, have made mistakes in not doing something I should have done, and doing what I should not have done,” Red Cloud said.

But he always kept his focus on his people. Six years before he died in 1909, the Lakota chief addressed his tribe for the last time. By then, he’d gone completely blind.

“My sun is set,” Red Cloud said. “My day is done. Darkness is stealing over me. Before I lie down to rise no more, I will speak to my people… I was born a Lakota and I shall die a Lakota.”

Chief Red Cloud died on Dec. 10, 1909, leaving behind a powerful legacy. Many of his descendants have gone to lead the Lakota just like he did.

But though he lived a remarkable life — taking on the U.S. Army and emerging victorious — he also recognized the fruitlessness of his war. The U.S. government conceded defeat without changing its behavior.

“They made us many promises, more than I can remember,” Chief Red Cloud said before his death. “But they kept but one — They promised to take our land… and they took it.”

After reading about Chief Red Cloud, discover the story of Chief Joseph, who attempted to work with the U.S. government through diplomacy. Or, learn the full, tragic tale of the Trail of Tears.