For 381 straight days, virtually no people of color rode on Montgomery, Alabama buses — and it helped catalyze the entire American civil rights movement.

Rosa Parks, a catalyst of the civil rights movement in America.

Following Rosa Parks’ December 1955 arrest, upon refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, the black community of Montgomery, Alabama — which comprised approximately 75 percent of the city’s bus-riding population — organized a movement that would hit the city right in the pocketbook.

After the 381st day, it ended segregation of the city’s buses altogether. Here’s how it happened, and why the story doesn’t actually begin with Rosa Parks…

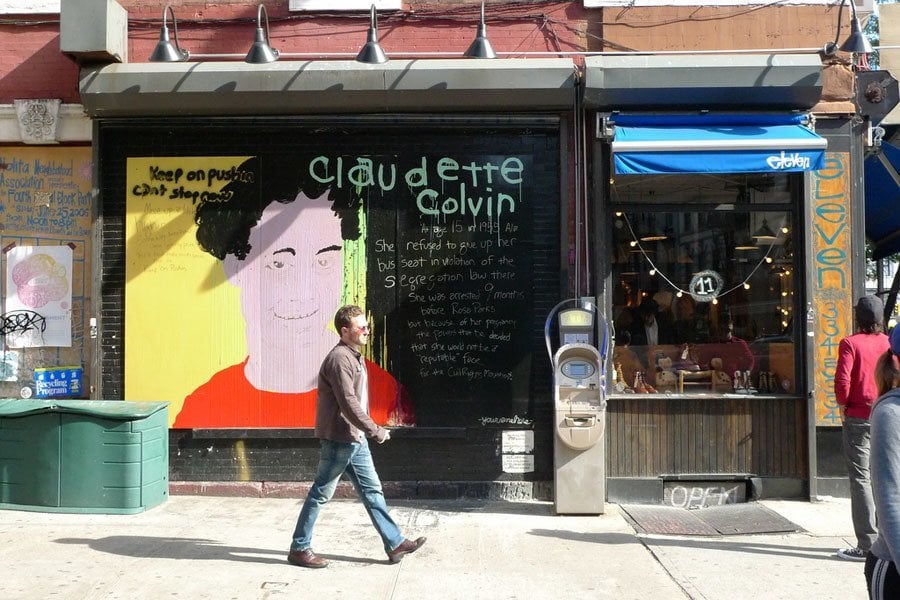

Street Art featuring Claudette Colvin. Image Source: Flickr

Found in violation of the Jim Crow laws, Claudette Colvin was just 15 years old when she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white person on a bus. Even though Colvin was arrested nine months before Parks, she was not deemed a “suitable” face for the movement since she was discovered to be pregnant shortly after the incident.

Before Colvin, there was Aurelia Browder; before her, Mary Louise Smith. Before Smith, there was Irene Morgan, and before her, famous baseball player Jackie Robinson.

Indeed, all of these people defied bus segregation policies and were persecuted for their actions. It was only when the respected and educated Rosa Parks refused to move that the King-headed Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was formed and organized a sustained bus boycott behind the more sympathetic plaintiff that was Rosa Parks. Even still, that came after the Women’s Political Council called for a Montgomery bus boycott on the night of Parks’ arrest.

The 1955 arrest of Rosa Parks. Image Source: Flickr

In comparison to what would later transpire, MIA’s original demands were humble: courteous treatment by bus operators; employment of Negro bus drivers, and first-come, first-served seating with a fixed dividing line.

The latter was especially important because at the time, whites filled in seats from the front, and black riders did the same from the back. When the bus had reached capacity, the black riders closest to the front — the “white section” — had to relinquish their seats and stand if another white person boarded the bus.

With a first-come, first-served policy, it would be harder for drivers to enact their prejudice against black riders. After all, Parks was sitting immediately behind the “white section” the day she was arrested for her failure to move from her seat. Had a solid barrier been imposed, it would have been harder — at least in a legal sense — for the driver to demand that she move.