For decades, forced sterilization was legal in dozens of U.S. states. A recently-discovered filing cabinet shines light on how racist the program was.

Wikimedia CommonsScientific papers of the Third International Congress of Eugenics held at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, August 21-23, 1932.

The use of forced sterilization to weed out human “undesirables” is a chapter of American history that most would like to forget. That’s difficult to do, though, since hundreds of its victims are still alive today.

Many have argued that these survivors should receive government compensation, since a government-funded procedure stripped them of the ability to have a family. But compensation — already a complicated process — becomes even more difficult when so many of the victims are unknown.

That’s why in 2007, when historian Alexandra Minna Stern opened a forgotten filing cabinet to find the hidden names and medical records of almost 20,000 Californian forced sterilizaiton patients, she knew she had discovered something big.

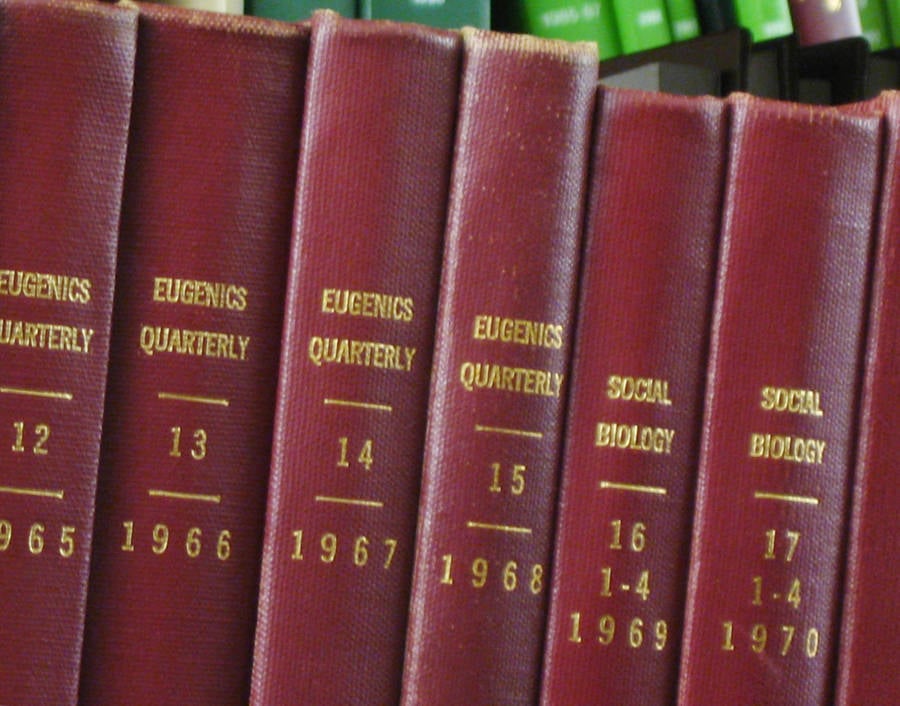

Wikimedia CommonsJournals in an anthropology library, showing when Eugenics Quarterly was renamed to Social Biology in 1969 as eugenics gradually fell out of favor in America.

Forced Sterilization: An Inspiration For Hitler

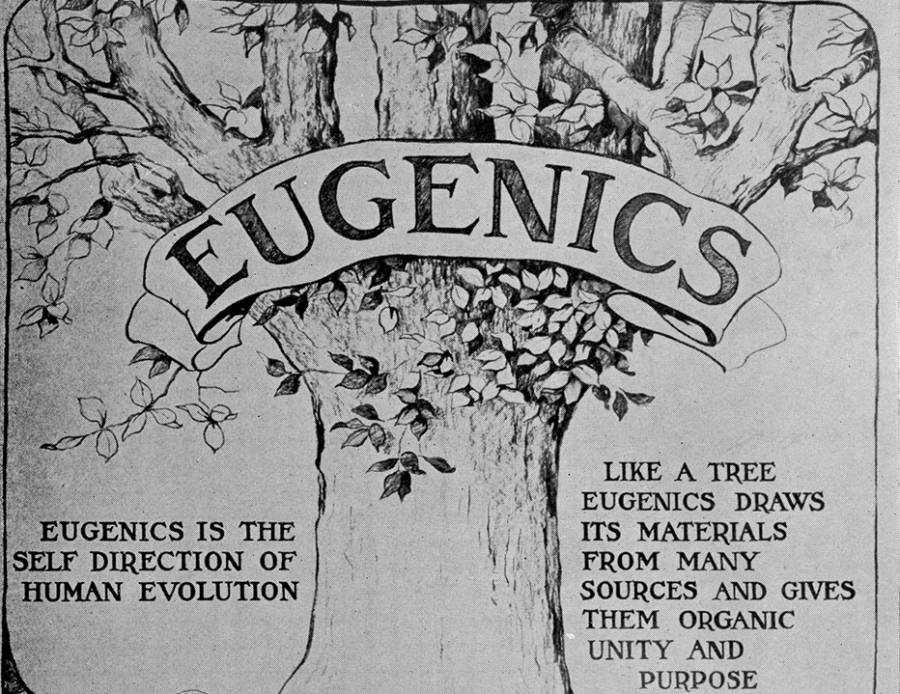

Eugenics, along with sterilization, is the science, or social philosophy, of controlled breeding that is most commonly associated with Nazi Germany. But Hitler did not come to this inhumane form of selective procreation by himself.

Forced sterilization — prompted by low IQ levels, physical handicaps, so-called moral degeneracy, overactive sex drives, racism, and bias against poor people — was actually something he picked up from The Land of the Free.

“There is today one state in which at least weak beginnings toward a better conception (of citizenship) are noticeable,” he wrote in Mein Kampf. “Of course, it is not our model German Republic, but the United States.”

From 1909 to as late as 1979, more than 60,000 forced sterilization procedures were performed in the 32 states where they were legal. One third of them were done in California.

“It’s hard to imagine today, but it was such an enormous fad that it was in all the popular magazines,” Adam Cohen, the author of a book on the topic, told NPR. “You know, it was being touted as a way to really uplift humanity. It was taught in hundreds of universities, all the best schools – Harvard, Berkeley. On and on, they taught eugenics courses. It was just everywhere, and it’s striking how few opponents it had.”

States gradually repealed the laws as the civil rights movement took off in the 1960s and 1970s.

Still, parts of the practice’s legacy live on today. For instance, in a 2013 report, the Center for Investigative Reporting found that almost 150 female inmates were sterilized in two California prisons from 1997 to 2010.

The women, who underwent the procedure without the necessary state approval, were targeted by state-contracted doctors and have since spoken out against the violation of their rights.

And now, with the unearthed filing cabinet of 20,000 forced sterilization victims discovered by Alexandra Minna Stern, evidence of the practice’s lingering influence is even more prominent.

The Discovery

City of San BernardinoPatton State Hospital, which sterilized thousands of patients in California. 1990.

Stern had already published a book on eugenics when she was directed to the filing cabinet where 19 reels of microfilm hid containing California state hospital records from 1919 to 1952.

The forms, which were well-preserved, showed the patients’ names and family histories, along with the medical recommendations that they be sterilized. Recognizing the potential impact of such a trove of information, Stern and her team from the University of Michigan set out on a three-year mission to enter and organize the data.

“Our dataset reveals that those sterilized in state institutions often were young women pronounced promiscuous; the sons and daughters of Mexican, Italian, and Japanese immigrants, frequently with parents too destitute to care for them; and men and women who transgressed sexual norms,” Stern wrote.

She published two of the most interesting results of their analysis in two different papers:

First: Patients with Spanish surnames were 3.5 times more likely to be sterilized — indicating discrimination in the medical and legal community.

And second: As many as 831 of the Californian patients are possibly still alive today, with an average age of 87.9 years.

In the latter report, Stern and her colleague urge California to quickly follow the examples of Virginia and North Carolina — which gave around $20,000 to each of their own resident survivors.

“Given the advanced age and declining numbers of sterilization survivors, time is of the essence for the state to seriously consider reparations,” they write.

Money won’t be able to give these elderly citizens what they lost, but it’s something.

“Most important, it shows the victims that they matter,” a Los Angeles Times op-ed reads. “They have value and they are equally important to the community.”

Intrigued by this look at forced sterilization? Next read about American eugenics and whether Nazi research contributed anything valuable to medical science. Or check out a history of family planning in the 19th century.