In many ways, modernity can be viewed as little more than the the product of centuries of dumb luck. As you are about to see, some of the world’s most significant milestones were the result of nothing more than happy accidents.

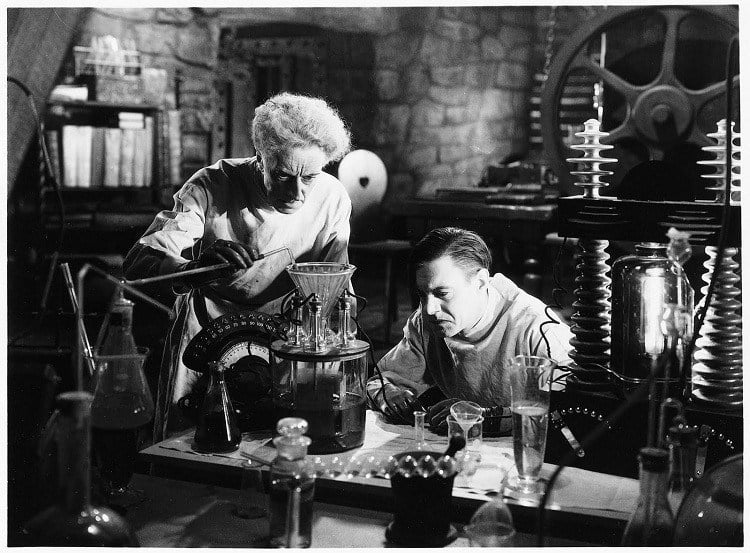

Accidental Discoveries: Penicillin

Source: ABC News

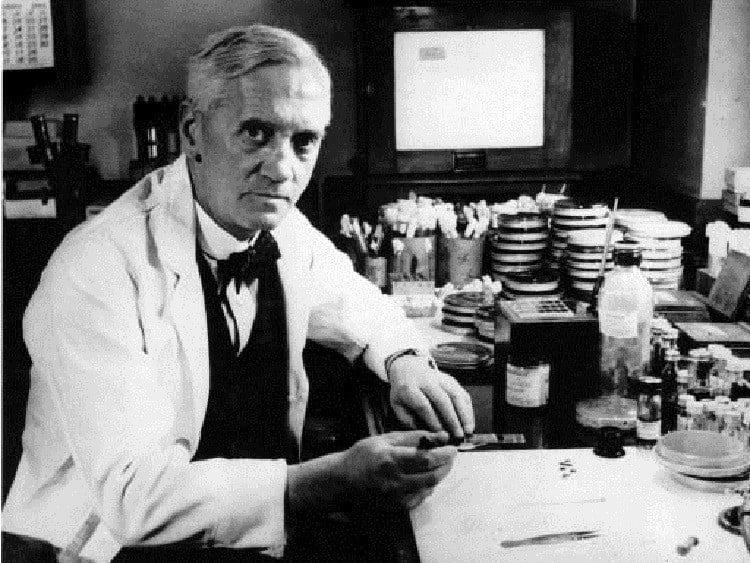

Scottish biologist Alexander Fleming changed modern medicine and saved countless lives by not being a very tidy man. Fleming left for vacation in 1928, failing to clean up his lab beforehand. When he returned, he noticed that some of his Petri dishes had developed mold that prevented bacteria to grow on them.

Alexander Fleming won the Nobel Prize in 1945 for discovering penicillin.

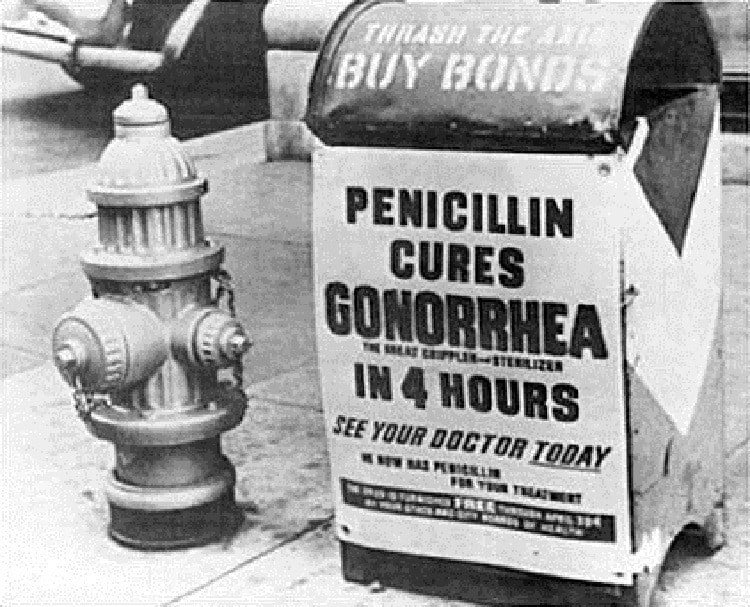

Correctly guessing that the mold had antibacterial properties, Fleming went to work on identifying the culture – Penicillium notatum. From that, the scientist was able to extract penicillin and revolutionize the world of antibiotics.

Penicillin became a panacea for all sorts of illnesses Source: Wikipedia

It should be noted that it took another decade before other scientists found a way to create a stable strain of penicillin that could be mass-produced. Likewise, Fleming wasn’t the first person to see the potential of moldy cultures.

Other prominent scientists such as Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister also realized that certain molds could inhibit bacteria growth, not to mention the fact that moldy bread was a traditional infection remedy since ancient times.

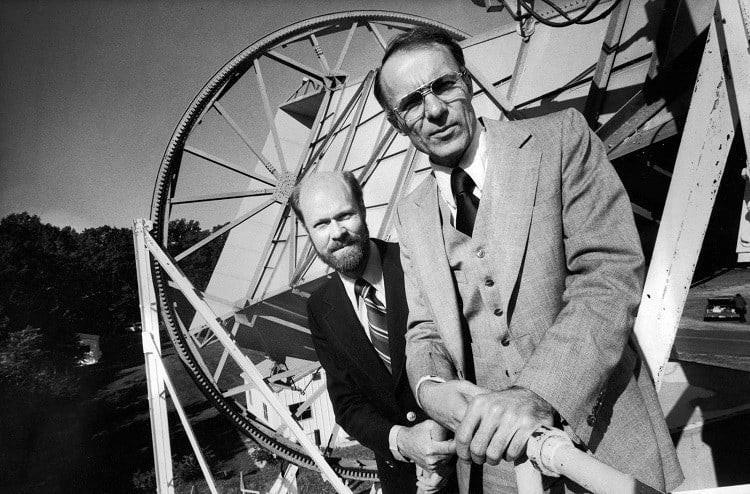

Accidental Discoveries: The Big Bang Theory

Source: io9

We aren’t actually talking about the discovery of the Big Bang theory itself, but rather of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), or the radiation that the Big Bang left behind. George Gamow predicted its existence in the 1940s but it wasn’t until 1964 that two radio astronomers, Robert Wilson and Arno Penzias, discovered it completely by chance.

For their work, Wilson and Penzias won the Nobel Prize in 1978.

Penzias and Wilson were working at Bell Labs in New Jersey and experimenting with a state-of-the-art horn antenna when they picked up some weird interference. At first, they thought this was due to something way less exciting than the CMB – pigeons. However, once they cleared the nest, they noticed that the interference remained. It could only be CMB.

The Holmdel horn antenna was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989 Source: Wikipedia

And thus the two astronomers discovered the first compelling evidence for the veracity of the Big Bang theory. At that time, the origins of the universe were in even hotter debate than today, with camps divided primarily by those who believed in an expanding universe (first put forward by Belgian priest/scientist Georges Lemaitre and later supported by Russian physicist George Gamow) or steady-state theory, the idea of a universe that always was and always will be. The discovery of the CMB tipped the scales in the Big Bang’s favor.

X-Rays

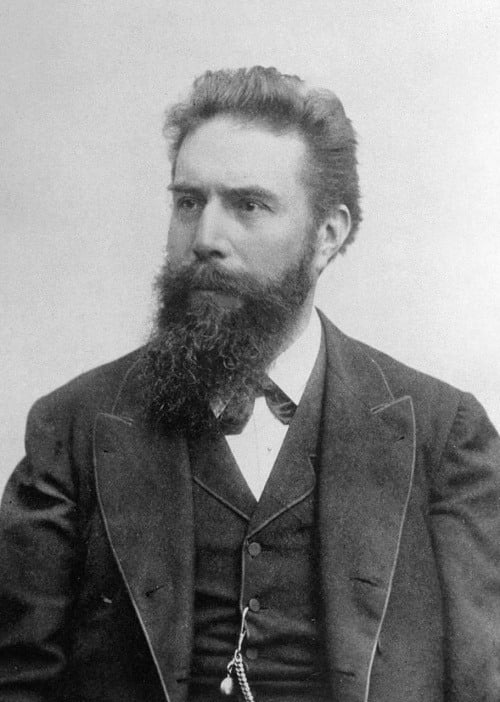

In 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen was doing some simple experiments with a cathode ray tube. At one point, he noticed that the tube was lighting a piece of fluorescent cardboard in the room even though there was a screen between them. Röntgen unsuccessfully tried to block the rays and eventually thought of sticking his hand in front of the tube, revealing the bones inside it. He had just discovered X-rays.

Wilhelm Röntgen won the first ever Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 Source: Wikipedia

To be fair, others were aware of the effects of X-rays before Röntgen, but he was the one to study them systematically. He also gave them their name, even though they were referred to as Röntgen rays for decades following his discovery.

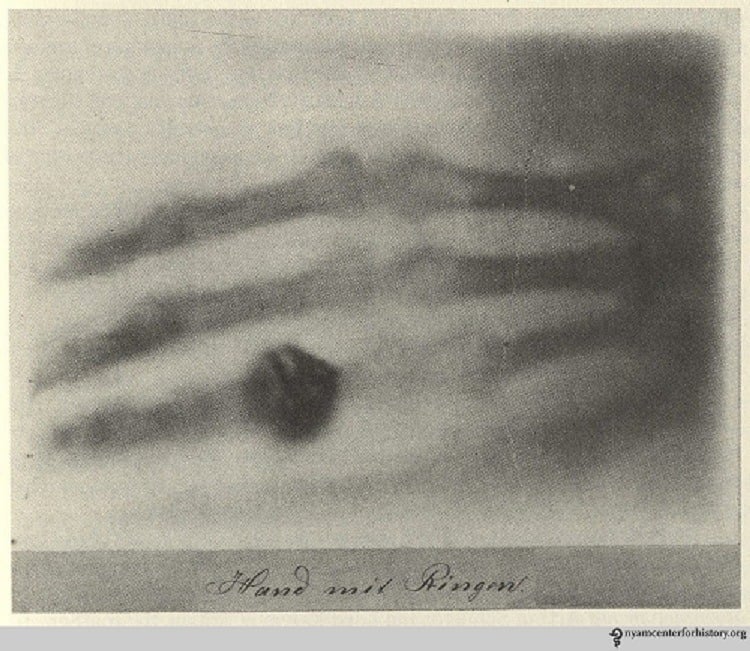

Anna Bertha Rontgen’s hand under x-ray Source: Nyam Center for History

Röntgen went to work on improving the imaging process by replacing the screen with a photographic plate so the images would be clearer. The first medical x-ray ever taken was of his wife’s hand, which Röntgen presented to the scientific community. Pretty soon x-ray technology became an international medicinal staple.

Radioactivity

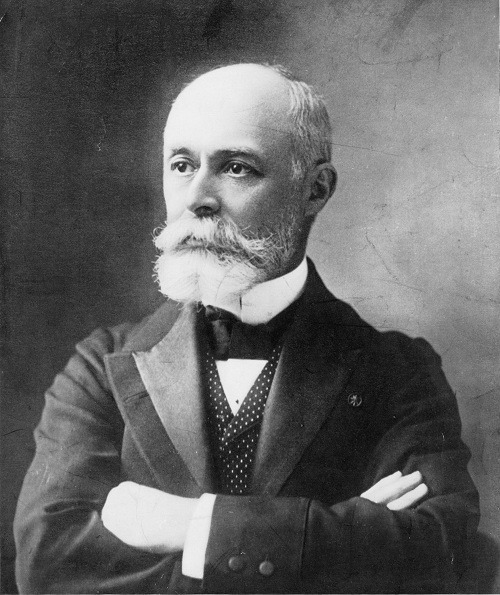

One happy accident often leads to another. That was the case with French scientist Henri Becquerel, who, after being inspired by Röntgen’s work, started researching phosphorescence in 1896. Becquerel thought that phosphorescence was responsible for the x-ray effect so he tried exposing some photographic plates to phosphorescent salts in order to confirm it.

Unsurprisingly, Henri Becquerel also won the Nobel Prize, an award he shared with Pierre and Marie Curie in 1903.

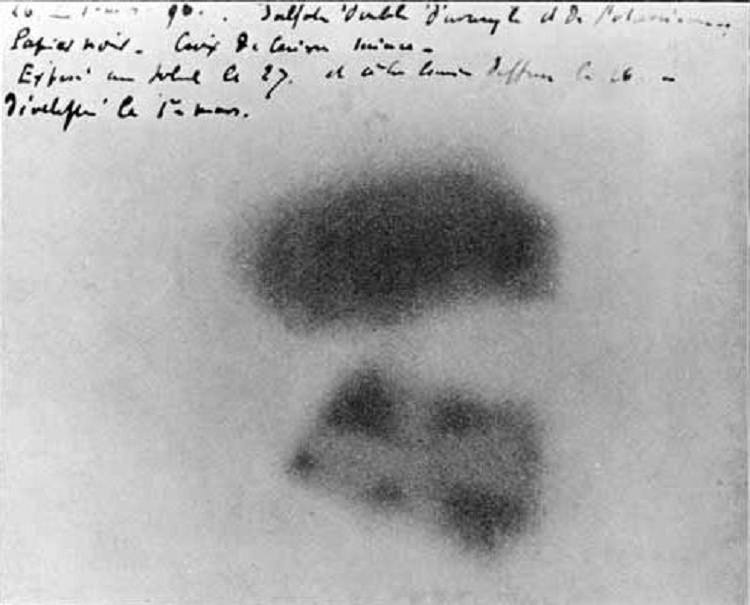

None of the materials used ended up having an effect, save for one: uranium salts. And even still, that discovery was made completely by chance. Becquerel considered sunlight to be essential to the experiment, and it was cloudy on the day he planned to test the uranium salts. Becquerel stuck everything in a drawer and waited to experiment another day, only to find days later that the uranium salts caused the photographic plate to blacken in spite of the darkness.

The photographic plate blackened by uranium salts Source: Wikipedia

Becquerel had wrapped the plates in paper so they were never in direct contact with the uranium salts, which meant that some unknown form of radiation capable of passing through solid objects was responsible for this event, not phosphorescence. Becquerel had stumbled upon radioactive decay or, as more know it, radioactivity.

Wearable Pacemaker

Source: Pacemaker People

With over 350 patents to his name, it’s a wonder that Wilson Greatbatch is not a household name. But of all his innovations, the wearable pacemaker is undoubtedly the most highly acclaimed.

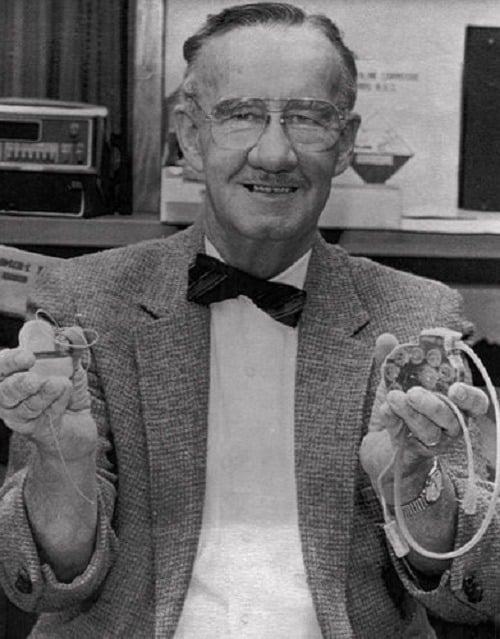

William Greatbatch holding his original creation in his right hand and a 1980s model in his left Source: The New York Times

In 1956, Greatbatch was an electrical engineer working to build a heart rhythm-recording device. In a serendipitous moment of inattention, he reached into a box of spare parts for a resistor, but grabbed the wrong size. Greatbatch realized this after installing it, but he also noticed that the completed circuit produced an electric pulse at a speed of 1.8 times per second.

Pacemakers existed before Greatbatch, but they were the size of TVs, weighed around 100 pounds and could only be used temporarily Source: Brown University

That’s roughly as fast as the heart beats, something Greatbatch immediately picked up on. He realized that the electrical stimuli could be used to assist a weak heart and went to work on shrinking down his device. In 1958 he successfully inserted a pacemaker into a dog, but it was left to a Minneapolis medical company to develop wearable pacemaker for humans that same year.