Over the course of four wars in six decades, Adrian Carton de Wiart proved himself to be the most badass soldier of all time.

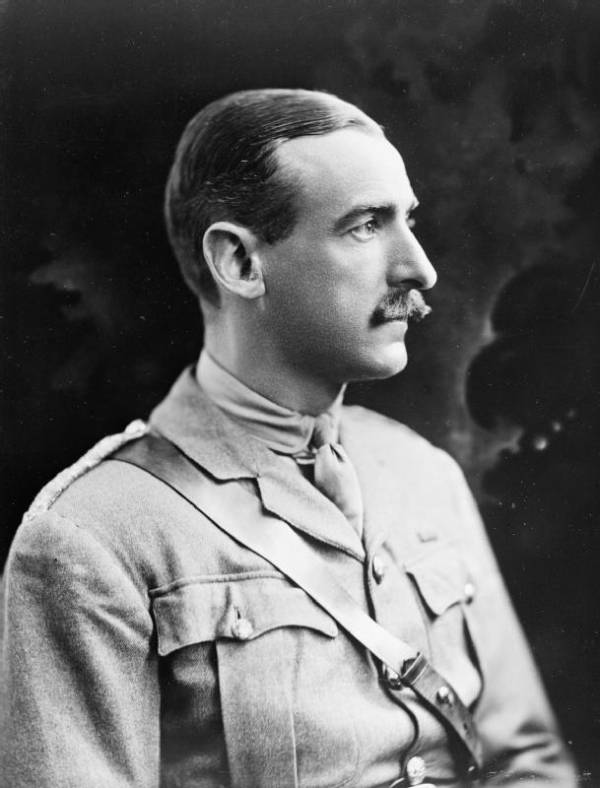

Wikimedia CommonsAdrian Carton de Wiart. 1944.

Adrian Carton de Wiart may be the most unkillable soldier to ever live.

For most soldiers, the loss of their left eye and left hand would be enough to force them to retire from battlefield service. Not so for Belgian-born British Army officer Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart. Over the course of four conflicts, he sustained 11 grievous injuries, which included being shot in the face, head, hand, stomach, leg, groin, and ankle.

As if that wasn’t enough, he survived numerous plane crashes, made multiple escape attempts from an Italian P.O.W. camp, and broke his back.

Despite all of these injuries, he remained fully dedicated to military service. For example, although he married an Austrian countess and they had two daughters, he makes no mention of them in his memoir.

Instead, his remembrances are devoted almost exclusively to his wartime exploits. And with his memoir entitled Happy Odyssey, it is plain to see that Adrian Carton de Wiart lived for warfare.

In his memoir, he recalled his thoughts when the Second Boer War broke out between Britain and two Boer states of South Africa in 1899, “At that moment, I knew once and for all that war was in my blood. If the British didn’t fancy me, I would offer myself to the Boers.”

At the time he was just a teenager, but Adrian Carton de Wiart was a bold, larger-than-life figure from the very beginning. He was born in 1880 to a Belgian aristocrat, though a rumor circulated that his real father was Leopold II, the King of Belgium.

“War was in my blood.”

Carton de Wiart’s brushes with death started after he left Oxford University to enlist in the British Army in 1899. He faked his name and age to qualify for combat in the Second Boer War and was soon on his way to South Africa. There he was shot in the stomach and groin and was sent to recover in England.

In 1901, he returned to South Africa for active duty. This time he enlisted under his real identity and served as a commissioned officer until the war ended in 1902.

In 1907, he became a British citizen and for a few years played aristocrat, shooting fowl and fox around Europe. He also made time to marry and start a family.

Wikimedia CommonsAdrian Carton de Wiart before he lost his eye.

Then, in 1914, World War I broke out and Carton de Wiart was back in military service. His first campaign was to quell a rebellion in British Somaliland. There, as part of the Somaliland Camel Corps, he rode into battle against the forces of Somali leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, dubbed “Mad Mullah” by the Brits.

Despite the Brits’ successful assault on a Somali fort, things did not go so well for Carton de Wiart. He was shot twice in the face, losing his left eye and part of his left ear. The defeated Somali side also, reportedly, lost some body parts when “Mad Mullah” had them castrated for their failure.

As for Carton de Wiart, he lost an eye and gained a Distinguished Service Medal (DSO) — and a glass eye. But he soon found that the glass eye aggravated him, so he allegedly flung it out a taxi window and opted instead for a black eye patch.

“I honestly believe that he regarded the loss of an eye as a blessing as it allowed him to get out of Somaliland to Europe where he thought the real action was,” said Lord Ismay, who fought alongside Carton de Wiart in Somaliland.

By early 1915, he was fighting in the trenches on the Western Front. During the Second Battle of Ypres, Carton de Wiart’s left hand was shattered by a bombardment from German artillery. According to his memoirs, he tore off two of his own fingers after the doctor wouldn’t amputate them. Later that year, a surgeon removed his now mangled hand entirely.

“Frankly, I had enjoyed the war.”

Undeterred — and seemingly unimpaired — he went on to fight in the Battle of the Somme, during which his men recall seeing the now one-handed man pull pins from grenades with his teeth and then flinging them with his one good hand into enemy territory.

He further distinguished himself in battle during the assault on the village of La Boisselle, France in 1916, when three unit commanders from the 8th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment were killed. Carton de Wiart then took charge of all three units and together they managed to hold the advancing enemy back.

For his bravery, the 36-year-old Carton de Wiart was awarded the Victoria Cross. But he humbly made no mention of it in his memoirs, claiming “it had been won by the 8th Glosters, for every man has done as much as I have.”

Wikimedia CommonsDelville Wood, sometimes known as Devil’s Wood, where Adrian Carton de Wiart survived being shot through the back of the head. 1918.

As was the case at La Boisselle, Carton de Wiart’s ability to lead from the front in some of the biggest hellholes of World War I accounted for the sheer number of critical injuries he suffered. In the trenches of Devil’s Wood, for example, he received what would normally be a kill shot to the back of the head — but survived.

During three subsequent battles, he was shot in the ankle, hip, and leg but soon regained full mobility after he convalesced. His final bullet wound was a relatively superficial one to his ear.

Despite his losses of various body parts, he said: “Frankly, I had enjoyed the war.”

And wherever there was a war, Adrian Carton de Wiart was sure to find it. Between 1919 and 1921, he commanded the British effort to aid Poland, which was engaged in multiple conflicts with the Soviet Bolsheviks, the Ukrainians, the Lithuanians, and the Czechs over coveted territory.

In 1919, he survived two plane crashes, one of which resulted in a brief period of Lithuanian captivity. Then, in August 1920, Cossacks attempted to hijack his observation train. He took them on single-handedly armed only with a revolver. During the fight, he fell onto the track, but lept straight back onto the moving train and took care of the rest of them.

While posted in Poland, Carton de Wiart became quite taken with the place and decided to remain there after the Poles won the war in 1921. He retired with the honorary rank of major-general in 1923 and spent the next 15 years shooting daily at his Polish estate.

Unfortunately, peace was relatively short-lived for the Poles, who were devastated by attacks from both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union during the opening months of World War II. Carton de Wiart was forced to escape Poland and then headed back to Great Britain where he re-enlisted in the British Army.

Back in the fray, he was sent to Norway to take command of an Anglo-French force in 1940. But his arrival set the tone for the catastrophic mission to come. His seaplane was forced to land on a fjord when it was attacked by a German fighter plane.

In true Adrian Carton de Wiart style, he refused to get into a rubber dinghy because it would be a sitting duck. Instead, he waited in the wreckage until the enemy plane literally ran out of ammunition and flew off. Then a naval vessel was sent over, and he casually got in and was taken to shore.

Wikimedia CommonsPortrait of Adrian Carton de Wiart. 1919

Carton de Wiart didn’t last long in Norway. His forces were outgunned and undersupplied. Still, under his leadership, his forces managed to traverse over mountains and get to Trondheim Fjord, all while being bombarded by the German Luftwaffe, withstanding artillery strikes from the German navy, and avoiding German ski troops. Ultimately, the Royal Navy, while under bombardment, managed to ferry the men out of Norway to safely, and Carton de Wiart arrived in Great Britain on his 60th birthday.

In April 1941, Carton de Wiart was appointed by Winston Churchill to lead a British mission in Yugoslavia. But he never got there.

En route to Yugoslavia via Malta, his Wellington bomber suddenly took a nosedive into the Mediterranean. He and the British Royal Air Force crew took refuge on the wing until the fuselage started to sink. Then the 61-year-old Adrian Carton de Wiart helped an injured, struggling comrade swim the mile to shore.

As soon as they made it to the coastline, they were captured by the Italians. Carton de Wiart was sent to Vincigliata Castle outside Florence, where he was one of 13 high-ranking officers held prisoner.

There is was like something out of The Great Escape, but starring senior citizens. The prisoners refused to stay incarcerated and mounted numerous attempts to escape. Determined, they even excavated a 60-foot tunnel through solid bedrock over a labor-intensive seven months until six of them escaped in March 1943.

They dressed as Italian peasants, but a one-handed man with a black eye patch proved conspicuous, and after eight days, Carton de Wiart was soon returned to captivity. Yet the war wasn’t over for him, and there were still more escapades to be had.

The Italians decided they wanted to switch sides and took Carton de Wiart to Rome to help negotiate with the Allies.

On Aug. 28, 1943, he returned to Great Britain but was only back a month before he was given a new assignment, this time as Churchill’s special representative to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-Shek. Before heading to China, Carton de Wiart accompanied Chiang Kai-Shek to the Cairo Conference, where the Allies discussed Japan’s postwar future. After the conference, Carton de Wiart remained in China for four years, where he managed to experience yet another plane crash.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Cairo Conference, where Japan’s post-war future was outlined. Carton de Wiart stands to the far right. Nov. 22-26, 1943.

Finally, in 1947, he retired — even then sustaining yet another serious injury. On his way back to England from China, he stopped off in Rangoon and slipped down a flight of stairs, breaking his back and knocking himself unconscious. During his recovery, the doctors removed a huge amount of shrapnel from his war-torn body.

Depending on your perspective, Adrian Carton de Wiart was either the luckiest or unluckiest soldier to have ever lived. Perhaps a bit of both. After his time as a soldier ended, he published his memoir and spent most of his days fishing before dying peacefully in 1963 at the age of 83.

After this look at Adrian Carton de Wiart, read up on “Mad” Jack Churchill, the sword-wielding, bagpipe-playing badass of World War II. Then, see why the World War II heroics of Desmond Doss, the man behind Hacksaw Ridge, were too unbelievable even for Hollywood.