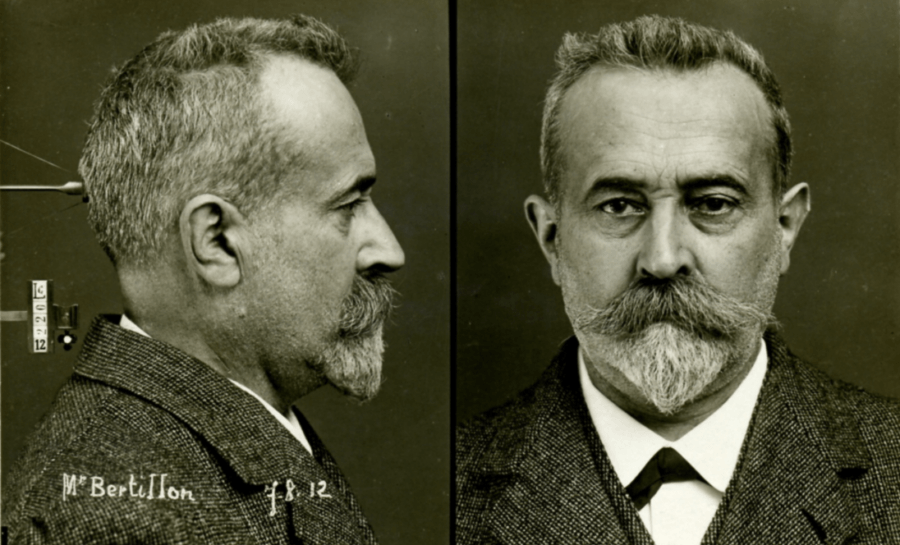

While working in a Parisian police station in 1879, Alphonse Bertillon conceived of a way to more accurately identify repeat offenders and became the first to photograph a crime scene.

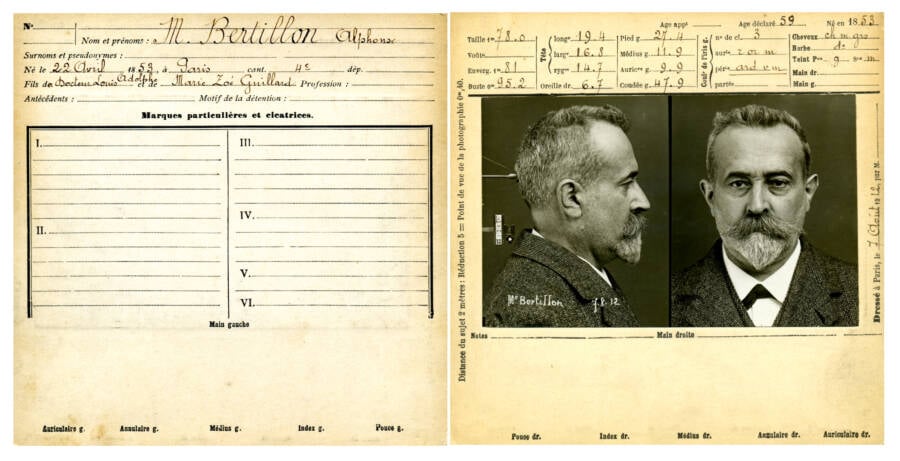

Préfecture de Police, Paris/Wikimedia CommonsAlphonse Bertillon developed the mugshot in the late 19th century. Here he is testing it out.

In the late 19th century, Sherlock Holmes became the very picture of the perfect detective. Yet, even author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle declared that Holmes was only “the second-highest expert in Europe.” He was outdone by a real-life French police officer named Alphonse Bertillon.

“To the man of precisely scientific mind,” Doyle said, “the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly.”

Alphonse Bertillon did prove more influential than Holmes when it came to solving crimes. He invented mugshots, crime scene photography, and much of forensic science itself. Indeed, more than anyone else of his time, Bertillon revolutionized criminology as we know it.

Why Detectives Struggled To Solve Crimes Before Alphonse Bertillon

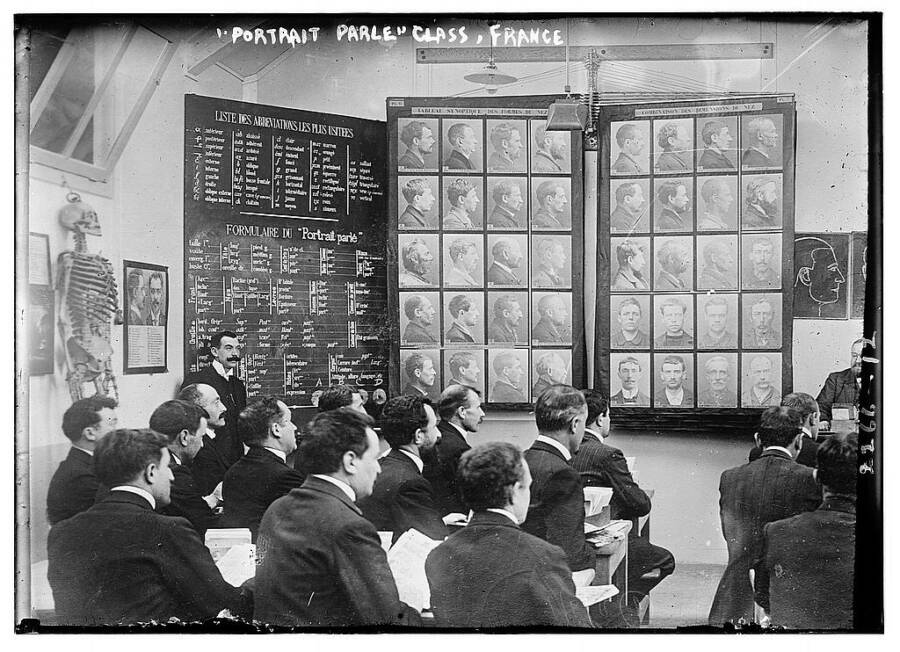

Bain News Service/Library of CongressA class of French police officers learning the Bertillon method, circa the 1910s.

The first publicly-funded police departments date to the early 19th century. This was long before fingerprints, blood types, and DNA offered forensic clues to crime solvers.

Tracking down suspects was also made that much harder when criminals could change their names, alter their visual appearance, and move to avoid detection with ease.

In the 1800s, police turned to a new technology — photography — to keep track of criminals. These so-called “rogues’ galleries” would collect photographs of convicts and repeat offenders. But there was no easy way to organize these galleries, leaving detectives stuck flipping through photographs and comparing them with descriptions of suspects.

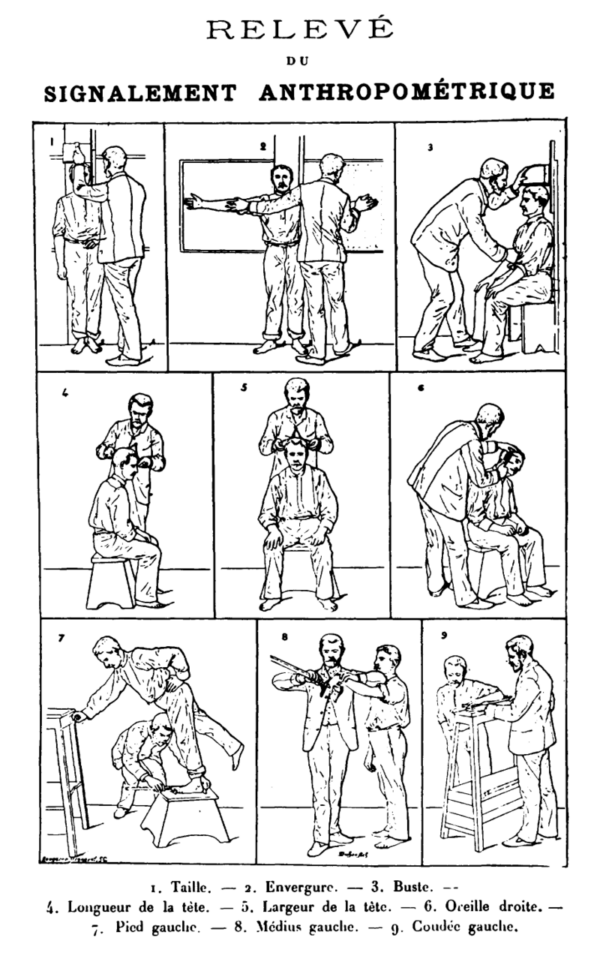

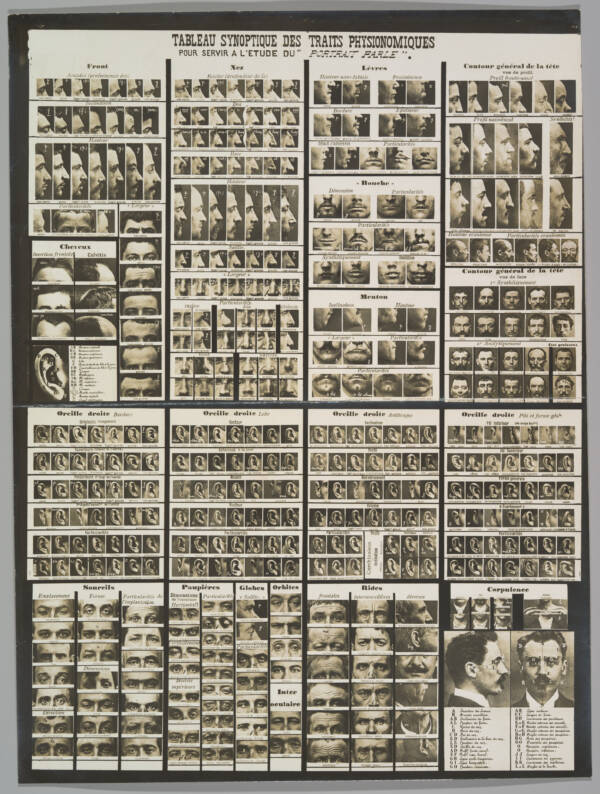

Alphonse Bertillon/Wikimedia CommonsMeasuring suspects was one of the most tedious parts of the so-called Bertillon method. In this 1893 chart, Bertillon explained how to take accurate measurements.

The end result was a mess. In 1879, Paris’s Préfecture de Police had collected 80,000 photographs and five million hand-written files with criminal data. The records were organized by name, giving criminals an easy way to avoid identification.

Police needed a better way to organize that information. They also needed a tool to identify people before drivers’ licenses and fingerprinting.

Enter: Alphonse Bertillon, a low-level clerk in the Paris police department with a knack for organization.

How The Bertillon Method Identified Criminals For The First Time

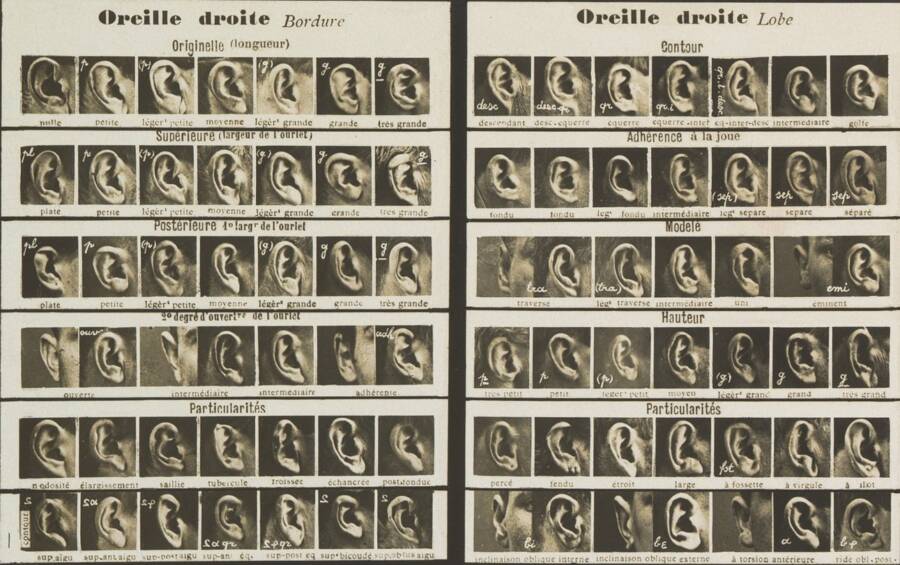

Alphonse Bertillon/The MetThe ears could help identify a criminal, Bertillon argued in his book. A profile mugshot helped police track down criminals by their ears.

Born in 1853, Alphonse Bertillon was the son of a doctor who applied statistics to medicine. When he grew up, Bertillon would adopt his father’s interdisciplinary nature, as he applied the cutting-edge science of anthropometry, or human measurements, to solving crimes.

After he was expelled from school, Bertillon held down a couple of odd jobs before his father found him work at the Parisian police department in 1879. The 26-year-old started in the records room, and while facing down tens of thousands of photographs and millions of records, Bertillon realized the police needed a more effective system of identifying and organizing criminals.

Préfecture de Police, Paris/Wikimedia CommonsBertillon showed police how to take measurements to identify criminals by measuring himself. On his card, Bertillon included his age, measurements, and mugshot.

So he turned to the science of human measurements. He noted that it was unlikely for any two criminals to have the exact same physical measurements, the odds would be more than four million to one, in fact. Criminals might be able to change their name, Bertillon further reasoned, but they couldn’t change the length of their middle finger or left foot.

He resolved to take careful note of 11 unique measurements, including head circumference, arm span, and foot and finger length. Once these were cataloged, police could more efficiently identify repeat offenders or weed out suspects.

“Every measurement slowly reveals the workings of the criminal,” Bertillon theorized. “Careful observation and patience will reveal the truth.”

Bertillon Implements Photography In Detective Work For The First Time

Alphonse Bertillon/The MetIn a 1909 chart, Bertillon detailed the unique identifying features on individual people.

Bertillon’s method didn’t stop with measurements. He also decided to include a photo of each criminal to accompany their physical details. Now known as the mugshot, these images included the face and profile of each suspect.

Unfortunately, police initially resisted implementing Bertillon’s method. Many laughed at the idea of tracking criminals by measuring their fingers, and besides, taking down each suspect’s measurements could be tedious work. Though the Parisian police department threatened to fire him for pushing his system, they did adopt his method in 1883.

From that point onward, whenever the police arrested suspects in Paris, they jotted down the person’s measurements on an index card. The police then organized the cards by the measurements, which made it easier for them to determine whether “John Smith” was the same man convicted of robbery or someone else.

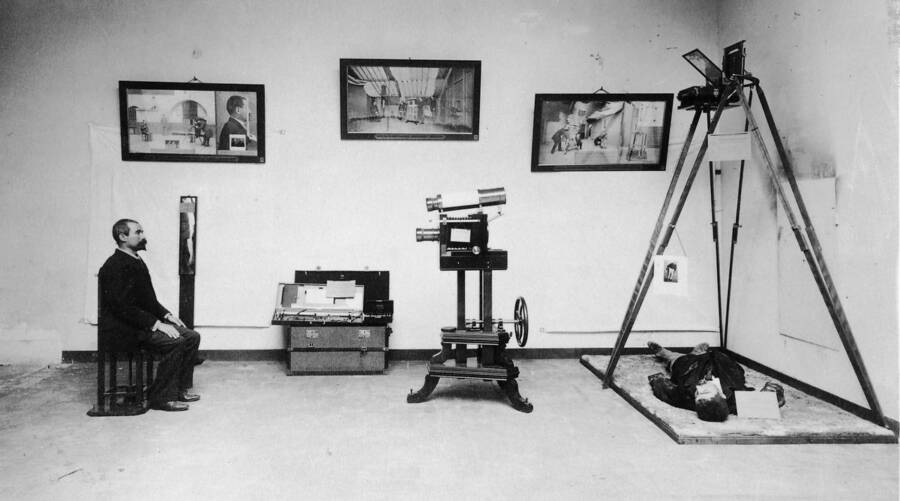

National Gallery Of CanadaBertillon’s exhibition of his photography method at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The following year, Bertillon used his system to sort through open cases and tracked down more than 241 repeat offenders. Because of his method, “Paris was the Mecca of police and Bertillon their prophet,” a German police department declared.

Bertillon’s mugshot method became even more popular than his measurement system. Criminals even developed this line as slang for getting arrested, “Giving a smile for the Bertillon studio.”

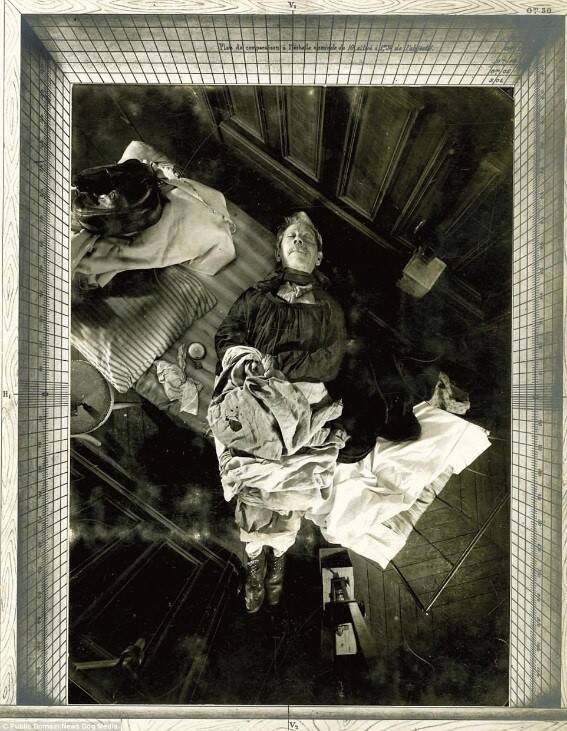

Besides mugshots and measurements, Bertillon developed a precise method for documenting crime scenes by using photography. He mounted a camera on a high tripod in order to record and survey each scene before investigators contaminated it.

Known as “metric photography,” Bertillon also employed grids in order to record the dimensions of the crime scene and the objects in it.

The Decline Of The Alphonse Bertillon Method

Public Domain/Alphonse BertillonUsing his high-mounted tripod, Bertillon took bird’s-eye view photos of murder victims, like this startling shot of Madame Veuve Bol, in Paris, 1904.

Though the Bertillon method was a major improvement when compared with earlier system, it was still difficult to use. Police had to make sure they recalibrated their measuring tools regularly and only a trained technician could take accurate measurements.

The method had other limitations as well. It didn’t work well for juvenile offenders, whose measurements changed as they aged. The same was true for older suspects.

Additionally, Bertillon didn’t always get it right when it came to detective work. He was an early critic of handwriting analysis and fingerprinting, which would eventually overtake his method.

Public Domain/Alphonse BertillonMonsieur Falla, murdered in his sleep and found in the corridor of his apartment in Paris, 1905.

In spite of his negative view of handwriting analysis, Bertillon’s expert testimony on Alfred Dreyfus’s handwriting sent the man to prison in the infamous Dreyfus Affair.

Still, today Bertillon is celebrated as one of the founders of forensic science.

In the early 20th century, Bertillon’s anthropometric method declined. Police departments instead turned to fingerprinting. But the criminologist introduced two other critical tools still used in modern policing: the mugshot and crime scene photographs.

Wilhelm Figueroa, who headed the NYPD photography unit, explained how police use the profile mugshot and a version of the Bertillon Method today.

“Take 10 different people, take pictures of their ears and you’ll be able to identify each and every one of them because we all have different facets to our ears. Some of us have longer earlobes, some shorter, some thicker, some thinner.”

Anthropometry may have faded away in policing, but Bertillon’s commitment to forensic science continues to shape crime-solving today.

Want to know more about the history of policing and solving crimes? Read about August Vollmer, the man who modernized policing in the early 20th century. Then, check out some of the most interesting vintage crime scene photos, in color.