In 1851, an American editor named Amelia Bloomer wrote an article in support of female pantaloons — inspiring women to wear a controversial garment called "bloomers."

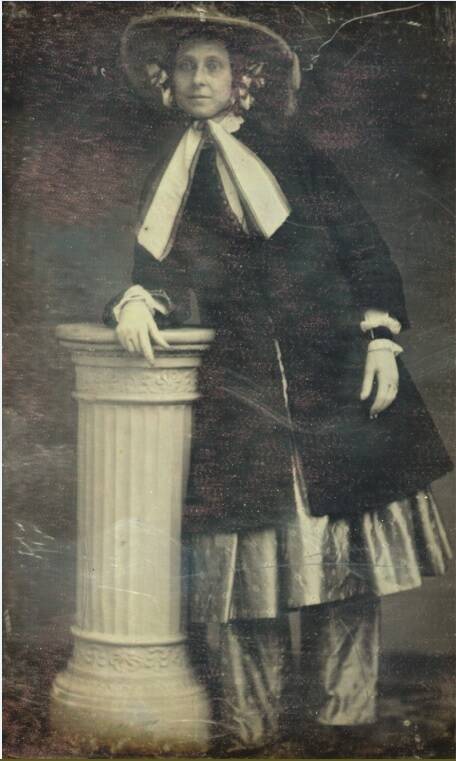

Getty ImagesAmerican suffragist Amelia Bloomer dared to suggest that women wear trousers under their skirts.

In the 1850s, crushing corsets, heavy skirts, and a half-dozen petticoats weighed women down as a literal hamper to their quest for liberation. So one women’s rights activist named Amelia Bloomer thought to change that by way of an outfit that became known as “bloomers.”

Even though bloomers still kept women covered from their necks to their feet, the garment sparked a backlash from anti-suffragists that was so fierce even Bloomer herself abandoned the new fashion.

As Amelia Bloomer’s suffragist friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton privately confessed, “Had I counted the cost of the short dress, I would never have put it on.”

This is the story of how bloomers completely backfired — and almost stalled the women’s rights movement in America.

Who Was Amelia Bloomer?

Seneca Falls Historical SocietyBloomer in the notorious pantaloons or “pantalettes.”

Born in 1818 in rural New York, Amelia Bloomer began her career as a humble teacher, but then she moved to Seneca Falls, a city that hosted a vibrant community of women’s rights activists.

In 1848, Bloomer attended the historic Seneca Falls Convention, where suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott discussed the condition of women’s rights in the United States.

The experience inspired Bloomer to found a newspaper called The Lily, which was dedicated to the growing fight for gender equality. It was the first American newspaper edited by a woman.

While encouraging increased access for women in education and in the ballot box, Bloomer waded into another major issue in the 19th-century women’s rights movement: fashion.

Victorian women were weighed down by pounds of petticoats and heavy corsets, a stark representation of their muted voices outside of the home. Additionally, the heavy styles of the mid-1800s weren’t just uncomfortable — they could prove deadly.

Tightly laced corsets impaired breathing, and flammable crinolines burned 3,000 women to death between 1850 and 1860. Additionally, bulky garments got caught in newfangled machines, injuring and killing women.

Bloomer thus wondered, could a change in style change the condition of women?

The Invention Of Bloomers

Library of CongressBloomers revolutionized Victorian fashion by raising hemlines and adding loose trousers, but the style also sparked harsh backlash.

In 1851, Amelia Bloomer read an editorial from a man who recently became supportive of the women’s suffrage movement in which he suggested that women adopt “Turkish pantaloons and a skirt reaching a little below the knee” as an alternative their current clothes.

The notion of loose pantaloons stuck with her.

Around the same time, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousin, Elizabeth Smith Miller, showed up in “Turkish trousers” that she’d designed herself.

Miller explained that long skirts impeded her work in the garden. In a moment of frustration, she declared, “This shackle should no longer be endured.” Miller donned “Turkish trousers to the ankle with a skirt reaching some four inches below the knee.”

Bloomer quickly adopted the style herself. Then, she promoted the new fashion to her readers.

The idea caught fire. Women wrote from across the country and subscriptions to The Lily skyrocketed. The outfit, once called a “freedom dress” or “Turkish pantaloons,” had earned a new name: bloomers.

“As soon as it became known that I was wearing the new dress,” Bloomer wrote, “letters came pouring in upon me by hundreds from women all over the country making inquiries about the dress and asking for patterns—showing how ready and anxious women were to throw off the burden of long, heavy skirts.”

Stanton declared that bloomers made her feel “like a captive set free from his ball and chain.” In August 1851, American suffragists made the trend international when they wore bloomers to the World’s Peace Congress in London.

The Backlash Against Amelia Bloomer’s Costume

Wikimedia CommonsIn the 1850s, women’s fashion demanded the widest skirts possible. Heavy petticoats and bulky skirts made it difficult for women to move.

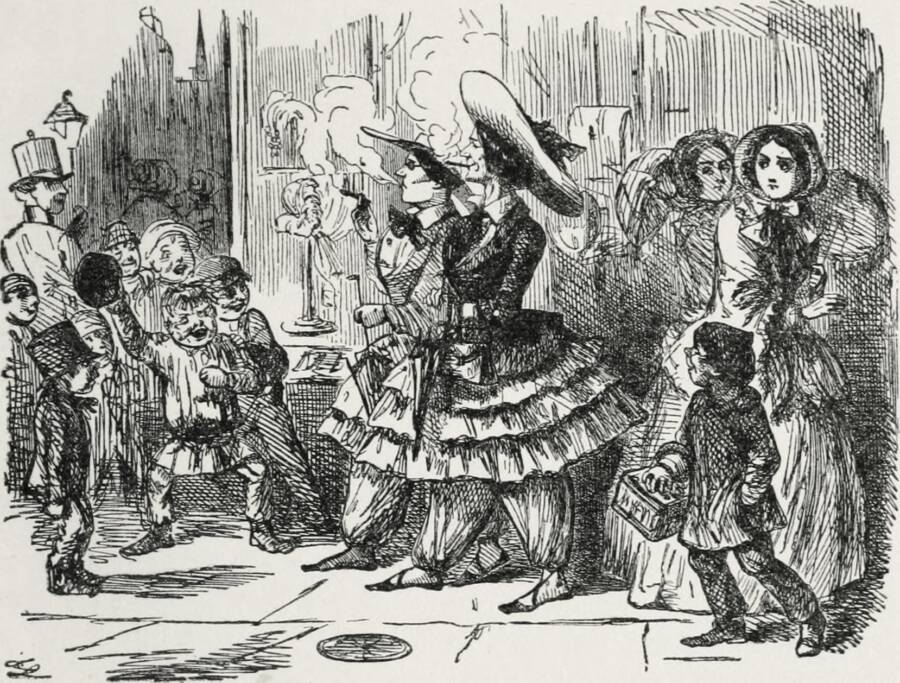

The style certainly caused an uproar. Magazines demonized bloomers as “a sort of shemale dress.” Gangs of boys harassed “Bloomerites” on the streets.

Stanton confessed that her own father banned her from wearing bloomers at his house and her sister “actually wept.” Men declared “they would not vote for a man whose wife wore the Bloomers.”

Stanton eventually gave up on bloomers herself, returning to “uncomfortable, inconvenient, and many times dangerous” Victorian dresses. “We put the dress on for greater freedom, but what is physical freedom compared with mental bondage?” She wrote. “By all means have the new dress made long.”

Punch/Wikimedia CommonsWomen who dared to wear bloomers marked themselves as radicals, according to critics. “Bloomerites” would surely break other gender norms, like smoking in public.

But Amelia Bloomer continued to wear her namesake trousers for years. She did eventually return to petticoats and full-length skirts and tried to frame the retreat as a victory.

“We all felt that the dress was drawing attention from what we thought of far greater importance — the question of woman’s right to better education, to a wider field of employment, to better remuneration for her labor, and to the ballot for the protection of her rights,” she wrote.

“In the minds of some people, the short dress and woman’s rights were inseparably connected. With us, the dress was but an incident, and we were not willing to sacrifice greater questions to it.”

Suffragists Abandon Bloomers

Wikimedia CommonsEven decades after Amelia Bloomer switched back to long dresses, bloomers were linked with “unfeminine” activities. On an 1890s cigar box lid, ladies who wear bloomers act like men.

Why did bloomers spark such a backlash? Amelia Bloomer had a theory. By donning pants, women visibly likened themselves to men. The bloomers hinted at a larger-scale “usurpation of the rights of man,” Bloomer lamented.

For generations, bloomers were linked with all kinds of subversive female behavior. Once women put on trousers, critics argued, they’d begin smoking cigars, working as police officers, and engaging in lewd behavior.

In Bloomer’s day, suffragists thus retreated to a less controversial fashion statement: Susan B. Anthony tied a simple red shawl around her neck. The Philadelphia Press lavished praise on Anthony for her “plain dress and quaint red shawl,” a look deemed appropriately matronly.

Anthony’s clothes offered “not a hint of mannishness but all that man loves and respects. What man could deny any right to a woman like that?”

Amelia Bloomer tried to improve women’s lives by lightening their burden and increasing their mobility. But trousers were men’s domain, and when women donned them, they threatened the gender order.

A quiet, red shawl could be forgiven — but bloomers were apparently too much.

Best known for her trousers today, Amelia Bloomer devoted her life to women’s suffrage. Learn more about the complicated history of the suffrage movement and then read about Mary Church Terrell, the daring Black suffragist left out of the history books.