While there are records of creatures appearing in court throughout history, animal trials peaked in popularity in Europe between 1400 and 1700.

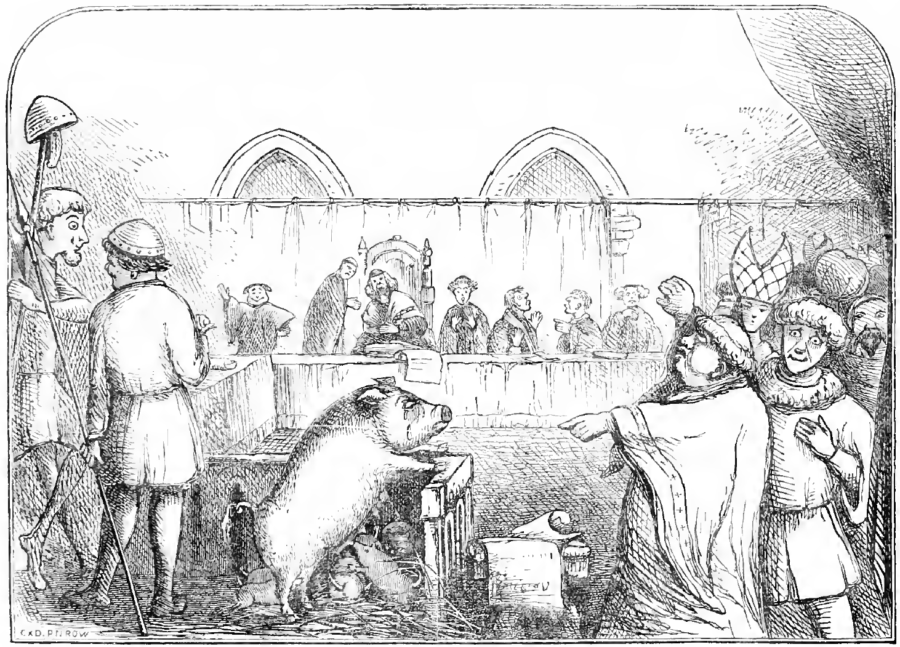

Public DomainThe 1457 murder trial of a sow and her piglets in Savigny, France.

Today, people in courtrooms around the world answer to judges and juries for crimes like property damage and murder. And in the not-so-distant past, so did animals. Animal trials were popular in Europe between 1400 and 1700 — but what exactly were they?

Creatures ranging from rats and locusts to pigs and donkeys were put on the stand — sometimes literally — to face charges for various transgressions. Some were even assigned lawyers to defend them.

There were two types of animal trials: secular and ecclesiastical. Domestic and farm animals, which were considered to be under the control of their owners, headed to secular courts. Critters like rats and other vermin, believed to be under the control of God, went to ecclesiastical church courts.

From there, animal trials played out much like typical human trials. And if the creatures were found guilty, they faced banishment — or worse.

Pigs, Cows, And Other Unlikely Criminals

One of the most famous animal trials took place in 1457 in Savigny, France. Robert Chambers’ 1869 Book of Days records the account of a sow and her six piglets who were accused of killing and eating a young child.

According to Chambers, “The sow was found guilty and condemned to death; but the pigs were acquitted on account of their youth, the bad example of their mother, and the absence of direct proof as to their having been concerned in the eating of the child.”

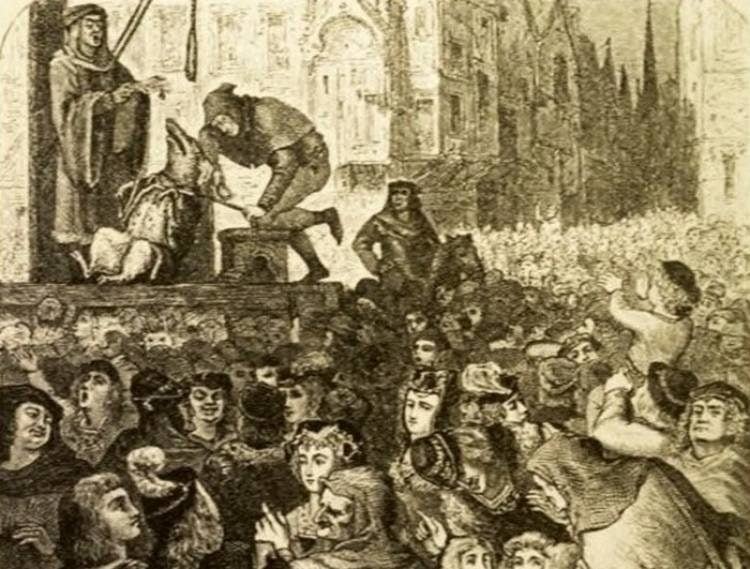

This wasn’t a rare event. Pigs were seemingly the most common animals that were put on trial. In European villages, pigs roamed freely and could grow large and dangerous. Sometimes they attacked small children. A 1386 case in Normandy likewise saw a pig sentenced to death for killing an infant in its crib. The sow was dressed in a white shirt and marched to the gallows. The entire town gathered to watch, and some farmers even brought their own pigs to witness the hanging so they would remain on their best behavior.

Other domestic creatures faced animal trials, too. In 1474, a rooster in Basel, Switzerland, was reportedly charged with laying an egg. This behavior was viewed at the time as unnatural and associated with witchcraft. Prosecutors argued that such an egg could be used in sorcery. A public defender retorted that the egg laying was an involuntary act, so the rooster couldn’t be held responsible. In the end, however, the rooster was burned with his egg.

Public DomainIn medieval times, some believed that the fearsome basilisk could be born from a rooster’s egg hatched by a serpent.

Sometimes, humans were put on the stand alongside their pets. In 1750, a peasant named Jacques allegedly sodomized his donkey, and both parties were charged with the crime. However, a character witness for the donkey testified that he was chaste, so he was acquitted, while Jacques was burned at the stake.

A similar case took place in Connecticut in 1662, when William Potter purportedly committed “the unnatural deed of carnal lewdness” with several cows, sheep, and pigs. They were all found guilty, and Potter had to watch each of his animals die before he was hanged himself.

Animal trials weren’t only for domestic creatures, though.

How Ecclesiastical Church Courts Carried Out Animal Trials

Since wild animals and pests like locusts, flies, and snails weren’t owned by people, they couldn’t be captured and executed. Instead, they were excommunicated or cursed, with church officials reading warnings to them in the fields where they lived.

In one famous case from 1510, a clever lawyer named Bartholomew Chassenée defended a group of rats accused of destroying crops. When the rats failed to appear in court, Chassenée argued they had stayed away out of fear of the local cats that roamed the streets. The court didn’t know how to respond to this, and eventually, the case was dropped.

Patrick Roper/Wikimedia CommonsRats sometimes faced trial for destroying crops or eating a town’s stores of barley and other grains.

Edward P. Evans, in his 1906 book The Criminal Punishment and Capital Prosecution of Animals, wrote that rats were often “sent a friendly letter of advice in order to induce them to quit any house, in which their presence is deemed undesirable.”

In 1519, the Alpine town of Stelvio, Italy, brought a case against moles (or possibly mice) for damaging crops. A lawyer argued that the rodents helped the soil and should not be punished harshly. The creatures were instead sentenced to banishment.

Though most of these cases occurred in France, Switzerland, and Italy, animal trials were not unique to Europe. They took place as far away as Brazil, New Zealand, and the Congo.

Still, the question remains: Why did anyone think it made sense to put animals on trial?

The End Of Animal Trials

Scholars today point to several reasons for animal trials. One is that medieval society believed strongly in a natural order set by God, with humans at the top. When that order was disturbed, such as a pig killing a child, people felt that it was important to take formal action to restore balance. Some trials also satisfied the community’s need for justice and revenge after a shocking crime.

Public animal trials also served as a warning to others. Officials wanted to show that they took crimes seriously and that no lawbreaker, human or animal, would go unpunished.

There may have been a financial motive, too. In a 2013 article published in The Journal of Law & Economics, economist Peter Leeson argued that church-run trials of pests helped increase tithe payments. If people saw the church cursing vermin, they might take its power more seriously and be more willing to pay what they owed.

Public DomainAn illustration of a pig’s execution.

What’s more, in the Middle Ages, unlike now, people treated animals more as sentient beings than as objects. Continuous human interaction with the animals they owned, which amounted to up to 16 hours per day into the 19th century, left owners with more sympathy for them.

Animal trials began to fade out with the rise of science and reason during the Enlightenment in the 1700s. Thinkers started to question how it made sense to punish animals that couldn’t even understand right from wrong. Around the same time, the idea of insanity as a legal defense took hold, which was a significant change in the justice system.

But animal trials never completely disappeared. In 1906, a dog in Switzerland was tried and executed for assisting in a robbery that led to murder. A chimpanzee was charged with smoking in a non-smoking zone during a circus act in Indiana in the 1920s. And in 2008, a bear in Macedonia was convicted of theft after stealing honey from a beekeeper. Since the bear was part of a protected species, the government ended up paying the damages.

Though we might laugh at the idea today, these animal trials tell us a lot about the past. They reveal how people made sense of tragic and unpredictable events happening in the world around them. And they remind us that even the strangest customs often had deep meaning to those who practiced them.

After learning about the bizarre history of animal trials, discover the causes behind the Salem witch trials. Then, read about the werewolf trials of Renaissance Europe.