The Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, or FLDS, is one of the largest and most infamous polygamist Mormon sects in history.

The Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, or the FLDS, sounds at first like it might simply be a different sect of the larger Mormon Church, but what started as a schism in beliefs soon evolved into the development of a cult rife with controversy, exploitation, and abuse.

After the LDS Church officially renounced polygamy in 1890 and doubled down in 1904, the FLDS emerged as a separate community in the Short Creek area of Hildale, Utah and Colorado City, Arizona. Their hierarchy is centralized around a single “prophet,” who claims to receive ongoing divine revelations, the most infamous of whom is a man named Warren Jeffs.

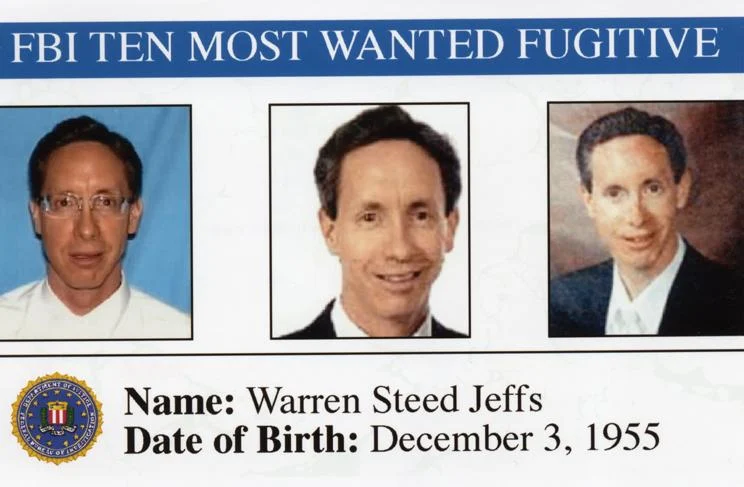

Jeffs officially became the FLDS leader in 2002 after his father, Rulon Jeffs, died, and brutally enforced a system of “placement marriage,” in which the prophet arranged marriages — including underage brides in polygamous marriages. Many of these young girls were forced to marry Jeffs himself, eventually earning him a position on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

Despite being sentenced to life in prison for child sexual assault back in 2011, Jeffs reportedly still leads the FLDS, while the church contends with legal battles over missing children, abuse allegations, and property rights.

The FLDS’ history is littered with controversies and crimes that have only recently been brought to light. Some former members have managed to escape the cult and speak out about the abuse, but for many others, the church’s teachings — and Jeffs’ influence — remain a part of everyday life.

The Troubling History Behind The FLDS

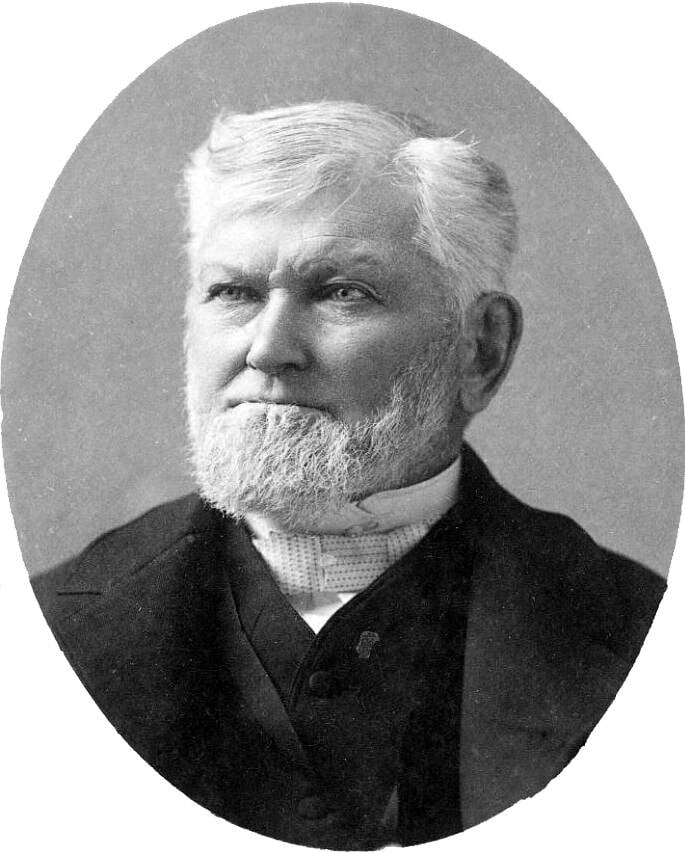

In 1890, the president of the Mormon Church, Wilford Woodruff, issued what became known as the "Manifesto," formally advising members to cease entering plural marriages in compliance with anti-polygamy laws in the United States. Congress had recently passed and enforced laws like the Edmunds-Tucker Act, seized church assets, and stripped polygamists of civil rights, steadily applying pressure to the LDS Church to end polygamy.

In response, Woodruff publicly stated the church's intention to obey the law and secure Utah's transition to statehood. The Manifesto was accepted during a general conference of church leaders in October 1890, which declared it "authoritative and binding" — though it notably only halted future plural marriages. Existing polygamist families were unaffected.

Despite this, various church leaders and members continued to enter plural marriages, and some had even set up new settlements in Mexico and Canada to continue the practice. So, in April 1904, new Church President Joseph F. Smith issued a more stringent declaration, threatening excommunication for anyone practicing polygamy. Still, not everyone in the church abided — and this led to a schism within the Mormon Church.

To those who believed that polygamy was divinely mandated, the Manifesto and the Second Manifesto were seen merely as societal compromise. Out of this group emerged the FLDS, the original followers of which claimed spiritual legitimacy over the 1890 Manifesto because of a purported divine revelation to former LDS Church President John Taylor in 1886.

Public DomainWilford Woodruff, the LDS president whose choice to follow anti-polygamy laws in the U.S. split the Mormon Church and paved the way for the emergence of fundamentalist Mormons.

This supposed revelation was outlined in a 1912 statement by Lorin C. Woolley, an advocate for plural marriage who claimed that he and a small group of other church figures had the irrevocable authority to continue to practice polygamy regardless of what other church leaders said. Woolley was excommunicated by the 1920s due to his allegations that the then-president and another church leader once had multiple wives.

Despite his excommunication, Woolley maintained a following that centered around a group called the Council of Friends, a precursor of sorts to the eventual FLDS. Even after Woolley's death, his influence remained, especially in the Short Creek area of Hildale, Utah and Colorado City, Arizona.

By the mid-20th century, though, the church's practices would make their way onto the national stage when Arizona state police and the National Guard raided the fundamentalist Mormon community of Short Creek.

How The 1953 Short Creek Raid Set The Stage For Warren Jeffs' Rise

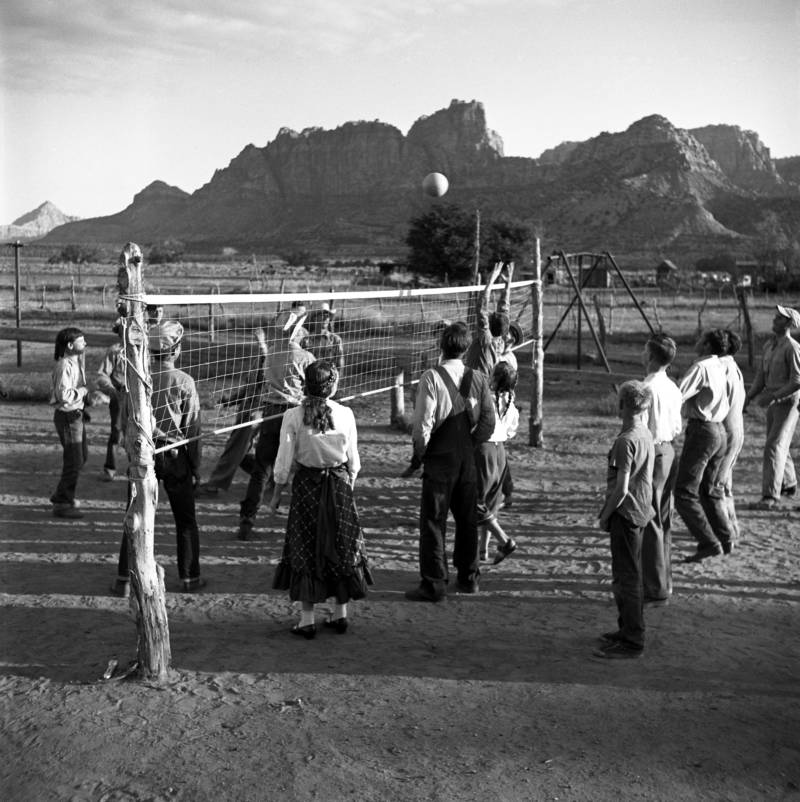

On July 26, 1953, Arizona law enforcement and the National Guard raided Short Creek in what would be the largest mass arrest of polygamists in American history. At the time, though, the move garnered criticism, with many of the opinion that this "show of force," as LIFE described it, was an overreaction, likening it to "hunting rabbits with an elephant gun."

At the time, the community of Short Creek was composed of around 400 people. The Attorney General's office had prepared 122 indictments — 36 men and 86 women — for insurrection. Those men were arrested and jailed in Kingman, while the women were forcibly sent off to Phoenix.

But that wasn't all. 263 children were placed in state custody, and though a superior court order in 1955 demanded that the children be returned to their families, some of the children wound up in foster care or remained otherwise separated from their families. Some never saw their parents again.

Law enforcement officials had also — foolishly, some might say with hindsight — made the decision to make the raid a media spectacle. They invited reporters and photographers to accompany them and document the event, not realizing that the public, upon seeing the photos of crying children being taken away from their parents, would not view the raid favorably. They also didn't realize that it would pave the way for the future FLDS.

"I just have such a strong emotional response [to these photos]," author Dorothy Allred Solomon, who has written about her experiences growing up in a polygamist community, told LIFE in 2014. "I was a little girl when these things happened, but I was conscious of them, and I was fully aware of the implications that families could be broken up."

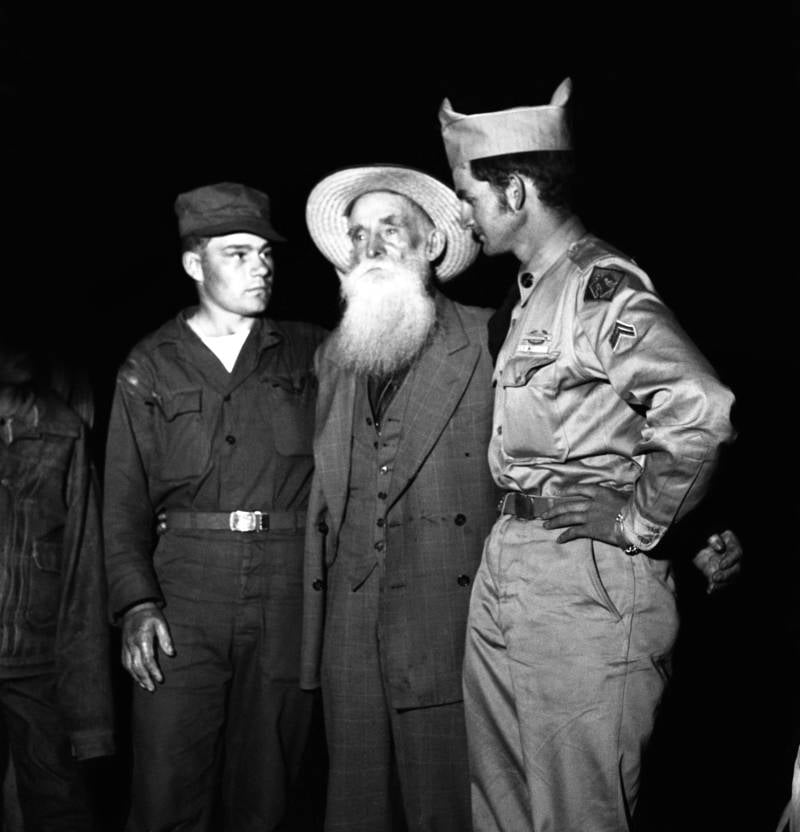

Public DomainMen from Short Creek gathered in a school's courtyard after the raid on their fundamentalist Mormon community.

Speaking to Deseret News, University of Utah professor Martha Sonntag Bradley explained that Arizona Gov. John Howard Pyle was extremely concerned that the men of Short Creek had been marrying young women and possibly girls, thus prompting the raid. Talking to the press shortly after, Pyle called the raid "a momentous police action against insurrection."

Pyle also compared the treatment of Short Creek's women to white slavery, saying it was "the foulest conspiracy you could possibly imagine." He was not the only official to make such a comparison.

"This is a white-slave factory," one assistant attorney general involved with the raid said. "No woman has escaped this community for at least 10 years. They are forced to submit to men old enough to be their grandfathers."

Despite Pyle and others' attempts to spin the narrative favorably, though, most couldn't help but see the raid as too extreme. A move that was meant to expose Short Creek's residents as misogynistic, pedophilic monsters instead had garnered sympathy as parents were separated from their children — children who likely had no idea what they had done wrong.

Media outlets questioned how children could be accused of being involved in an insurrection by simply existing, and some even called the move "un-American." Pyle tried to justify the raid. He had meant to send a message that polygamy would not be tolerated. The message was received, but the result was even more secrecy, as many fundamentalist Mormon polygamists "went way underground," according to Solomon.

"And when people go underground like that, it creates shadows and darkness for people like Warren Jeffs to exploit other people's paranoia," Solomon added. "The reason someone like Jeffs could come to power was because of this raid in 1953 — he totally used people's fears."

Life In Warren Jeffs' FLDS Cult Is Everything John Howard Pyle Feared

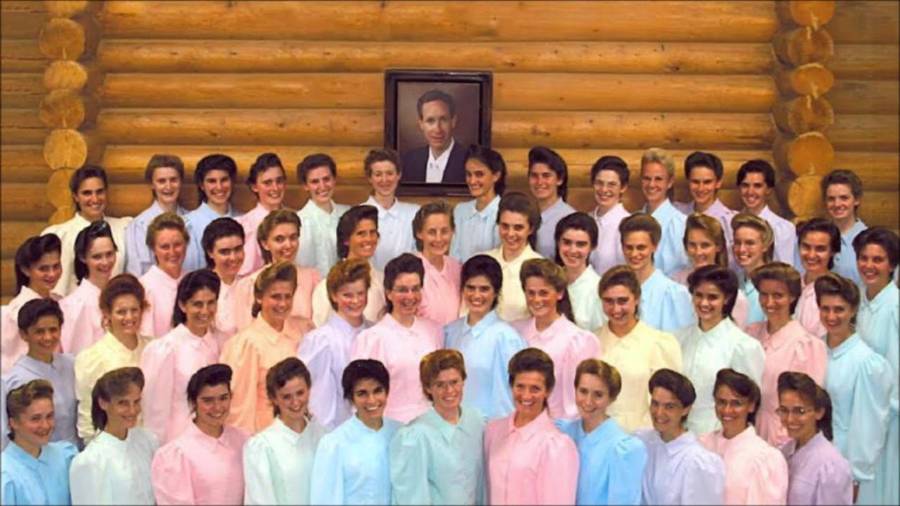

Rachel BlackmoreWarren Jeffs with 17 of his wives.

Polygamist groups spent a few years in quiet anticipation after the Short Creek raid, but rather than feeling demoralized, they were more resolved than ever before. The raid had shown that many members of the public were less tolerant of the government's meddling in their lives than they were of polygamy, and various splinter groups started to rise up.

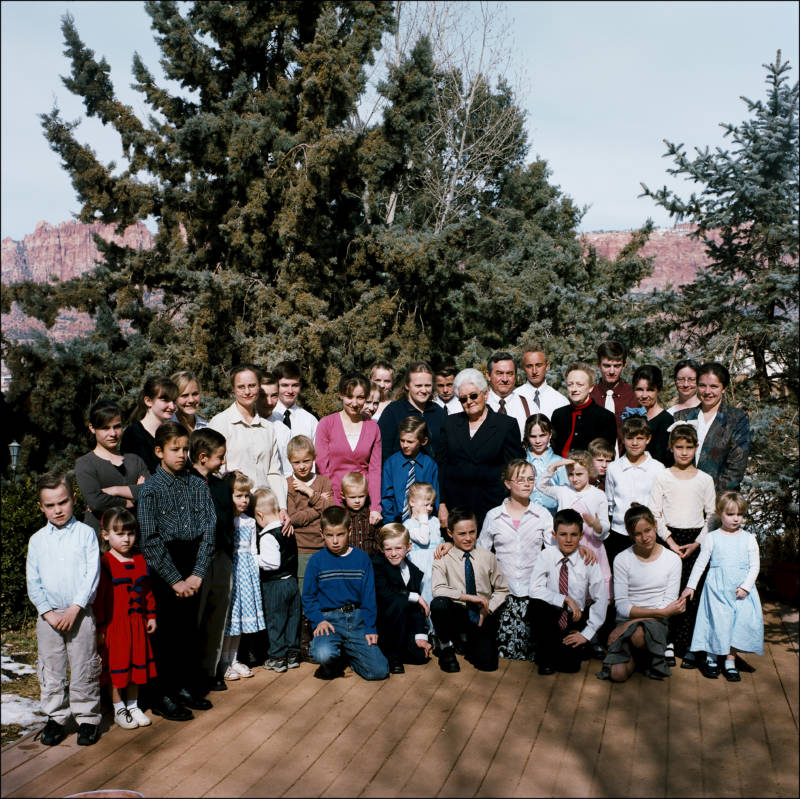

Eventually, a man named Rulon Jeffs incorporated many of these groups — including 10,000 people by the turn of the 21st century, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center — into the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. When the elder Jeffs died in 2002, his son Warren took over as prophet and soon began enacting a dictatorial regime.

Among Warren Jeffs' first moves were outlawing activities like swimming, watching television, listening to popular music, and even celebrating Christmas. Children were forbidden from playing with toys and games, and families could not own pets. All of this was meant to make the FLDS stricter and gain more control over the everyday lives of followers.

Jeffs' most infamous decision was assuming full control over "spiritual marriage," a foundational point of the FLDS' polygamy that says men must have at least three wives in order to reach the highest level of salvation. Jeffs, however, also claimed it was his divine right to assign wives to the men of his church — or reassign them, if a husband had deviated from the path of righteousness. He reportedly excommunicated younger men who he felt presented a threat to their elders in terms of accumulating wives.

Federal Bureau of InvestigationWarren Jeffs' FBI Most Wanted poster.

Warren Jeffs used his position to his personal advantage most often, though, indulging in his predatory desires. According to The Guardian, Jeffs married around 80 women and girls during his time as FLDS prophet. Along with preying upon his young "brides," he also spent much of his time promoting racism and homophobia among his followers, saying things like, "The Black race is the people through which the devil has always been able to bring evil unto the Earth." He also compared same-sex marriage to murder.

For all his hateful and negative statements about gay people and Black people, though, Warren Jeffs' attitude toward pedophilia was shockingly positive — so much so, in fact, that he engaged in it himself.

In 2005, Jeffs went on the run after a warrant was issued for his arrest on the charges of conspiracy to commit rape and sexual conduct with a minor. Before long, the FBI had placed him on their Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. In August 2006, Jeffs was arrested near Las Vegas during a traffic stop.

During his subsequent trials, the full extent of Jeffs' crimes was laid bare.

He was initially wanted for forcing a 16-year-old girl to marry an already married 28-year-old man, then he was hit with a subsequent charge of unlawful flight when he went on the run. His eventual arrest prompted a raid on one of his compounds, where investigators found evidence that he had also taken child brides — and engaged in sexual acts with girls as young as 12. Horrifically, teaching these young girls how to please him sexually was referred to in the church as "heavenly trainings."

By 2011, Warren Jeffs had been sentenced to life in prison plus 20 years for sexually assaulting a 12-year-old girl and a 15-year-old girl. But even from behind bars, he reportedly continued to dictate orders to his followers. Some reports surfaced of a memo in which Jeffs renounced his leadership, but it seems that many within the church still look to Jeffs for guidance.

Back in 1953, Arizona Gov. John Howard Pyle had feared that fundamentalist Mormon sects were abusing children and forcing young girls into marriage, but all the public saw was children being ripped from their parents while Pyle talked about insurrection. Decades later, his worst fears about the FLDS were proven to be true. The tragic irony is that Jeffs' rise was only made possible because of the Short Creek raid in the first place.

After this deep dive into the FLDS and the history of fundamentalist Mormons, read about how Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon Church, met his demise. Then, go inside the brutal murder of Brenda Lafferty at the hands of her fundamentalist Mormon brothers-in-law.