The Roman Empire was so crippled by the Antonine Plague that many scholars believe it hastened the empire's demise.

At the height of the Antonine Plague, up to 3,000 ancient Romans dropped dead every single day.

The disease was first cited during the reign of the last of the Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, in 165 or 166 A.D. Even though how the pandemic began remains unknown, one Greek physician named Galen managed to document the outbreak itself in startling detail.

Victims suffered for two weeks from fever, vomiting, thirstiness, coughing, and a swollen throat. Others experienced red and black papules on the skin, foul breath, and black diarrhea. Nearly ten percent of the empire perished this way.

Known as both the Antonine Plague and the Plague of Galen, the pandemic did eventually subside, seemingly as mysteriously as it had come.

The Antonine Plague rendered the empire of Ancient Rome a kind of Hell. Indeed, the most powerful empire of its time was utterly helpless in the face of this invisible killer.

The Antonine Plague Spreads Through Ancient Rome

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1820 portrait of Galen, the Greek physician who documented the Antonine Plague.

Sources largely agree that the disease first appeared in the winter of 165 A.D. to 166 A.D. It was the height of the Roman Empire.

During a siege of the city of Seleucia in modern-day Iraq, Roman troops began to take note of a disease among the locals and then its own soldiers. They consequently carried that disease with them to Gaul and further legions stationed along the Rhine river, effectively spreading the plague across the empire.

Though modern epidemiologists haven’t identified where the plague originated, it is believed that the disease likely developed first in China and was then carried throughout Euroasia by the Roman troops.

There is one ancient legend that attempts to describe how the Antonine Plague first infected the Romans. The legend proposed that Lucius Verus — a Roman general and later the co-emperor to Marcus Aurelius — opened a tomb during the siege of Seleucia and unwittingly liberated the disease. It was thought that the Romans were being punished by the Gods for violating an oath they’d made not to pillage the city of Seleucia.

Meanwhile, the ancient doctor Galen had been away from Rome for two years, and when he returned in 168 A.D., the city was in ruin. His treatise, Methodus Medendi, described the pandemic as great, lengthy, and extraordinarily distressing.

Galen also observed victims suffer from fever, diarrhea, a sore throat, and pustular patches all over their skin. The plague had a mortality rate of 25 percent and survivors developed immunity to it. Others died within two weeks of first presenting symptoms.

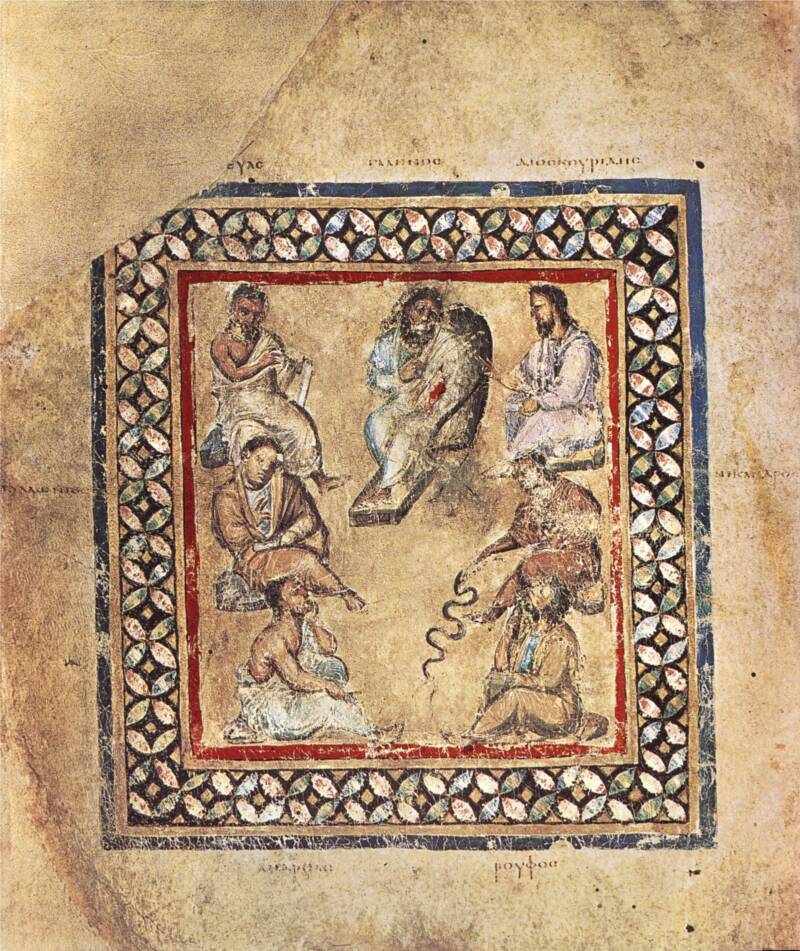

Wikimedia CommonsGalen (top center) and a group of physicians in an image from the sixth-century Greek-Byzantine medical manuscript, Vienna Dioscurides.

“In those places where it was not ulcerated, the exanthem was rough and scabby and fell away like some husk and hence all became healthy,” M.L. and R.J. Littman wrote in The American Journal of Philology of the disease.

Modern epidemiologists have largely agreed based on this description that the disease was probably smallpox.

By the end of the outbreak in 180 A.D., close to a third of the empire in some areas, and a total of five million people, had died.

How The Plague Of Galen Wounded The Empire

Wikimedia CommonsBoth Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (represented here in a bust from France’s Musée Saint-Raymond) and his co-emperor Lucius Verus may have died from the plague.

Of the millions that the plague claimed, one of the most famous was co-Emperor Lucius Verus, who ruled beside Emperor Antoninus in 169 A.D. Some modern epidemiologists also speculate that Emperor Marcus Aurelius himself perished from the disease in 180 A.D.

The Plague of Galen also heavily impacted Rome’s military, which then consisted of around 150,000 men. These legionaries caught the disease from their peers returning from the East and their resultant deaths caused a massive shortage in Rome’s military.

As a result, the emperor recruited anyone healthy enough to fight, but the pool was slim considering so many citizens were dying of the plague themselves. Freed slaves, gladiators, and criminals joined the military. This untrained army then later fell victim to Germanic tribes who were able to cross the Rhine river for the first time in over two centuries.

Wikimedia CommonsThis Roman coin commemorated the victories of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus during the Marcomannic Wars, which lasted from 166 to 180 A.D. — the year he died.

With the economy in trouble and foreign aggressors taking hold, financially maintaining the empire became a serious issue — if not impossible.

The Aftermath Of The Antonine Plague

Unfortunately, the Antonine Plague was only the first of three pandemics to destroy the Roman Empire. Two more would follow, devastating the economy and army.

The Antonine Plague begat a shortage in the workforce and a stagnant economy. Floundering trade meant fewer taxes to support the state. The emperor, meanwhile, blamed Christians for the pandemic, as they supposedly failed to praise the Gods and subsequently enraged them enough to unleash the disease.

Christianity, however, actually garnered popularity during this crisis. Christians were among the few willing to take in those suffering from or left destitute by the plague. Christianity was thus able to emerge as the singular and official faith of the empire following the plague.

As people from high classes fell to lower ones, the nation experienced collective anxiety about their own stations. This was previously unimaginable to those entrenched in Roman exceptionalism.

Ironically, it was the empire’s expansive reach and efficient trade routes that facilitated the spread of the plague. Well-connected and overcrowded cities once hailed as the epitome of culture quickly became the epicenters for disease transmission. In the end, the Antonine Plague was only a predecessor of two more pandemics — and the demise of the biggest empire the world had ever seen.

After learning about the Antonine Plague of Ancient Rome, explore the terrifying but necessary job of a medieval plague doctor. Then, learn about history’s most infamous plague and why it’s been tormenting humanity for way longer than we thought.