Centuries after the first wave of the Black Plague killed nearly half of Europe, we are still left wondering how the deadly plague subsided.

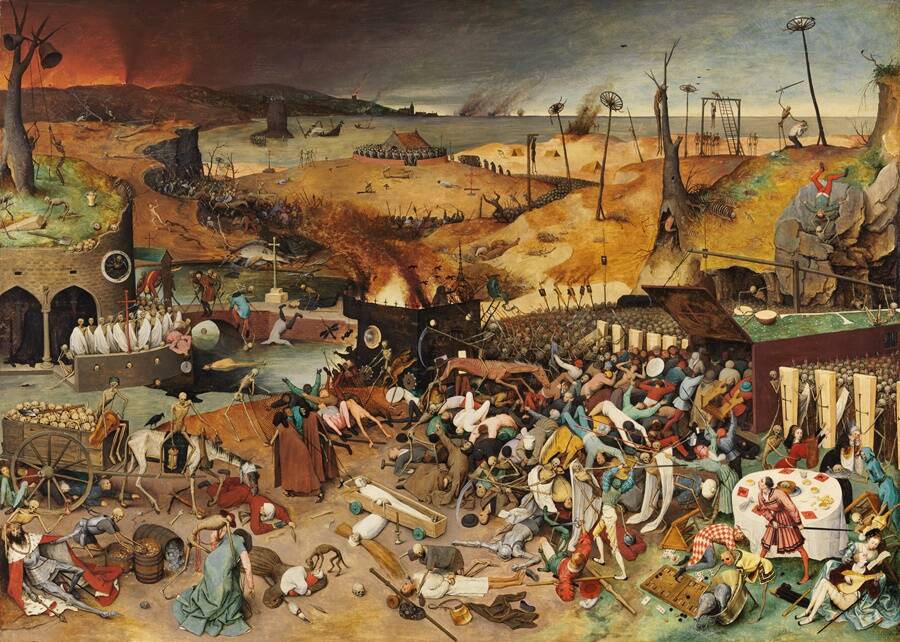

Wikimedia CommonsPieter Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death reflects the social upheaval caused by the Black Plague.

No pandemic in history was as deadly as the Black Plague. From the Middle Ages right up until the 1750s, the Bubonic Plague decimated Europe and the Middle East, wiping out an estimated 30 million people in the first decade alone.

The devastation was so great that Renaissance poet Petrarch, who observed the plight from Florence, wrote: “O’ happy posterity, who will not experience such abysmal woe and will look upon our testimony as a fable.”

But the plague did eventually subside, sometime around 1352 or 1353, reappearing in fragmented pockets every 10 to 20 years until the 18th century.

So how did the Black Plague end? And did it ever really disappear — or are we simply biding our time until a comeback?

The Course Of The Black Plague In The 14th Century

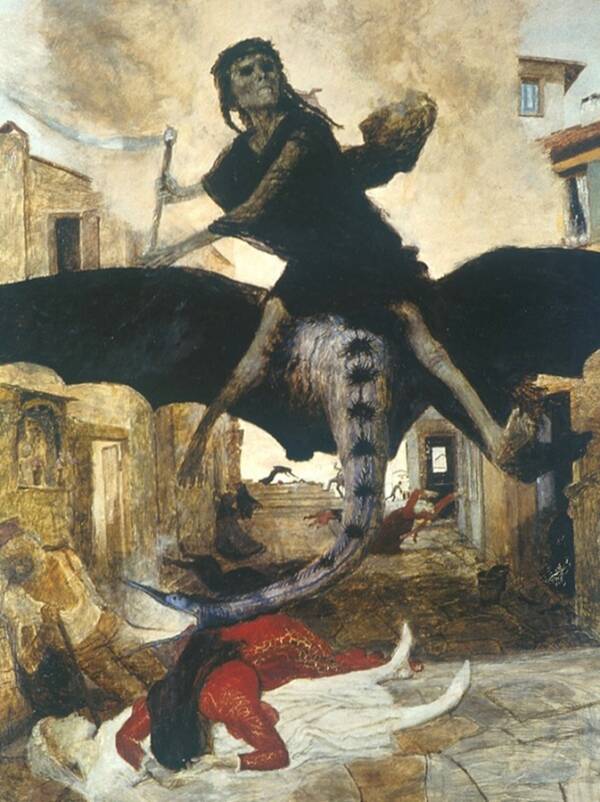

Public DomainThe Black Plague caused unrivaled devastation, killing 50 million people at its height.

The Black Plague, otherwise known as the Black Death or Bubonic Plague, remains the most deadly pandemic in world history. Experts believe that the name “Black Plague” was a mistranslation of the Latin word “atra mors” which could mean either “terrible” or “black.”

It was originally estimated that on average, a third of the population of affected areas was wiped out by the plague over its most destructive decade between 1346 and 1353, but other experts think that closer to or even over half of the entire continent of Europe’s population perished.

Plague victims suffered from excruciating pain. Their symptoms began with a fever and boils. A victim’s lymph nodes would swell as their body fought the infection and their skin would become strangely blotched before they began to vomit blood.

At that stage, the victim typically died within three days.

Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura described the grisly aftermath of the Black Plague in his hometown of Tuscany:

“In many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead…And there were also those who were so sparsely covered with earth that the dogs dragged them forth and devoured many bodies throughout the city.”

Di Tura himself had to bury his five children because of the plague.

Wikimedia CommonsThe flawed design of a Medieval plague doctor’s uniform did not actually protect them from infection.

Early researchers initially thought that the Black Plague began somewhere in China but more research has shown that it likely formed in the steppe region of Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

The first spread of the disease began, according to plague historian Ole J. Benedictow, in the autumn of 1346 when the Tartar-Mongols attacked the city of Kaffa (now Feodosiya) in Crimea.

During the siege, the Mongols catapulted plague-ridden corpses into Kaffa, effectively infecting the entire city — including the hundreds of Italian merchants who had come for trade.

In the spring, the Italians fled back home, carrying the disease on flea-ridden rats aboard with them. By early July 1347, the Black Plague had broken out all over Europe.

It quickly spread to Africa and the Middle East due to overseas trading and the growing density of cities.

Tracing the plague’s origins and spread was doable enough, but determining how the Black Plague ended is another story entirely.

How Did The Black Plague End?

Europe saw the worst of the Black Plague for nearly 10 years before the disease began to subside, yet it still returned every decade or so up until the 18th century. It was never quite as deadly as it was in the 14th century.

The Great Plague of London in 1665 is often considered the last major outbreak of the disease, though there are reports of the disease in Western Europe as late as 1721. Also, the Black Plague did continue to infect Russia and the Ottoman Empire well into the 19th century.

To this day, nobody knows exactly why or how the Black Death finally came to an end, but experts have a few compelling theories.

Some experts posit that the biggest possible reason for the plague’s disappearance was simply modernization.

People previously thought that the plague was divine punishment for their sins which often led to ineffective remedies that were grounded in mysticism. Alternatively, devout worshippers who did not want to go against “God’s will” stood idly by as the disease swept their homes.

But with advancements in medical science and a better understanding of bacterial diseases, there emerged new treatments.

Wikimedia CommonsThhis map illustrates the spread of the Black Death.

Indeed, the plague became an impetus for significant developments in medicine and public health regulation. Scientists of the time turned to dissection, the study of blood circulation, and sanitation to find ways to combat the spread of the disease.

The phrase “quarantine,” in fact, was coined during the outbreak of the Black Plague in Venice in the early 15th century. Historically, however, the policy was only first implemented by the Republic of Ragusa (present-day Dubrovnik in Croatia) in 1377, when the city shuttered its borders for 30 days.

Others suggest that the plague subsided due to the genetic evolution of human bodies and bacteria itself.

The reality, though, is that there is still much to be learned about the Black Plague and how it finally subsided.

An Unfortunate Resurgence

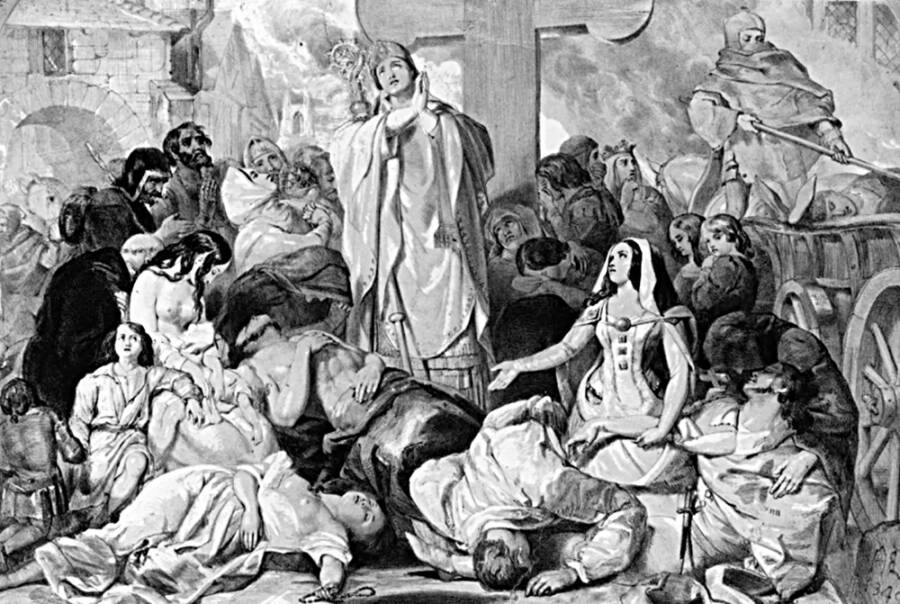

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIllustration of people praying for relief from the Black Plague which some people believed was a punishment from God.

The Black Plague was not the first major plague to besiege the world nor will it be the last.

During the sixth century, a major plague broke out in the Eastern Roman Empire that later became known as the First Plague Pandemic.

The Black Plague, which followed a few centuries later, was thus known as the Second Plague Pandemic. After that, another plague hit central and eastern Asian between 1855 and 1959, known as the Third Plague Pandemic, and this killed 12 million people.

Three different types of plagues have been identified by scientists: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic.

The Black Death is an example of bubonic plague, which has affected humans for at least 4,000 years.

Victims of bubonic plague form tender lymph nodes or buboes that leave spots of the body blackened due to internal hemorrhaging and it is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which can be found in wild rodents — mostly rats — that have been infected by disease-carrying fleas.

Today, the Black Death can be treated simply with antibiotics.

As of 2019, parts of the world still experience plagues, and most commonly, bubonic plague.

Roughly seven cases of the plague are reported each year in the U.S. The disease has only appeared in the western part of the country so far. Outside the U.S., Africa has been hit the hardest by the plague in modern times.

In 2017 and 2018, Madagascar experienced a devastating outbreak of pneumonic plague, a form which spreads rapidly between humans. Thousands of infections and hundreds of deaths occurred.

General Photographic Agency/Getty ImagesProtective clothing worn by doctors treating patients during the Great Plague of 1665.

Other parts of the world, such as Central Asia and parts of South America, are also still infected by minor outbreaks annually.

Deaths from plague now are certainly not comparable to the nearly 100 million people killed by the plague over the centuries. Still, our lack of understanding of this persistent disease is cause for concern.

As award-winning biologist David Markman noted, a plague is a disease of animals, and as humans encroach further on the habitats of wildlife, it becomes more likely that disease spreads between us.

For all we know, the next major plague could be lurking just around the corner.

After learning about how the Black Plague ended, discover what it was like to be a Medieval plague doctor. Then, read about how plague-carrying prairie dogs caused parts of Rocky Mountain Park to shut down in Colorado.