555-Million-Year-Old Fossils And The ‘Ancestor Of All Animals’

University of California, RiversideExperts thought that finding such tiny fossils was impossible — until new technology proved them wrong.

In March 2020, researchers made some mind-boggling archaeological discoveries when they found a fossilized, 555-million-year-old worm-like creature. Unearthed in Australia, this specimen is believed to be the first ancestor of all animals today — including humans.

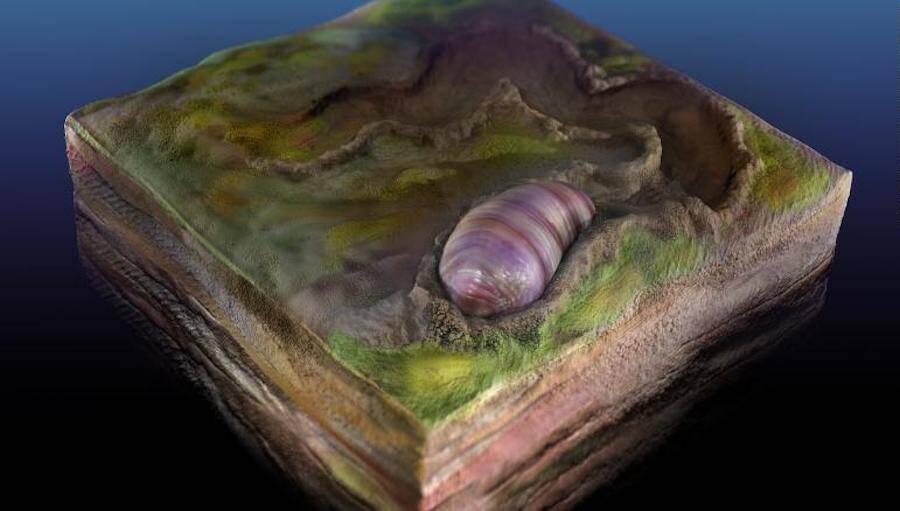

Dubbed Ikaria wariootia, this little creature is the earliest bilaterian — aka an organism with a front and back, two symmetrical sides, and openings at either end connected by a gut. This organism was only found thanks to the use of modern 3D laser scan technology.

“This is what evolutionary biologists predicted,” said Mary Droser, a geology professor at the University of California, Riverside. “It’s really exciting that what we have found lines up so neatly with their prediction.”

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal lays out why this find is so unprecedented. The earliest multicellular organisms, known as Ediacaran biota, had a wide range of shapes but most of them aren’t directly related to modern-day animals.

As a result, biologists have long posited that the oldest ancestor of all bilaterians was very small and simple, with just the basic sensory organs. That’s why many experts believed that it’d be too hard to find such a specimen. But when 2020 rolled around, experts in Nilpena, South Australia made some truly exciting archaeological discoveries.

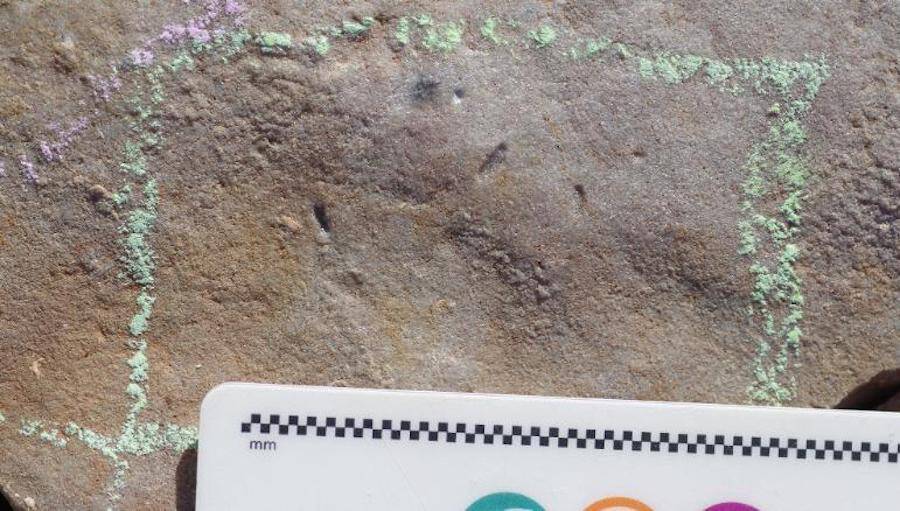

A series of 555-million-year-old burrows there has long been known to have been created by bilaterians. But without modern-day 3D laser scans, experts were unable to confirm as much. Finally, the technology confirmed the presence of impressions near these burrows, which were shaped and sized like a grain of rice. They also revealed clear heads, tails, and even grooves that suggested the presence of muscles.

“It’s the oldest fossil we get with this type of complexity,” said Droser.

University of California, RiversideThe ruler showcases just how small the creature’s fossilized burrows are.

The clear patterns of displaced sediment, as well as signs of feeding, suggested the creatures had mouths, guts, and posterior openings.

“We thought these animals should have existed during this interval, but always understood they would be difficult to recognize,” said doctoral graduate Scott Evans. “Once we had the 3D scans, we knew that we had made an important discovery.”