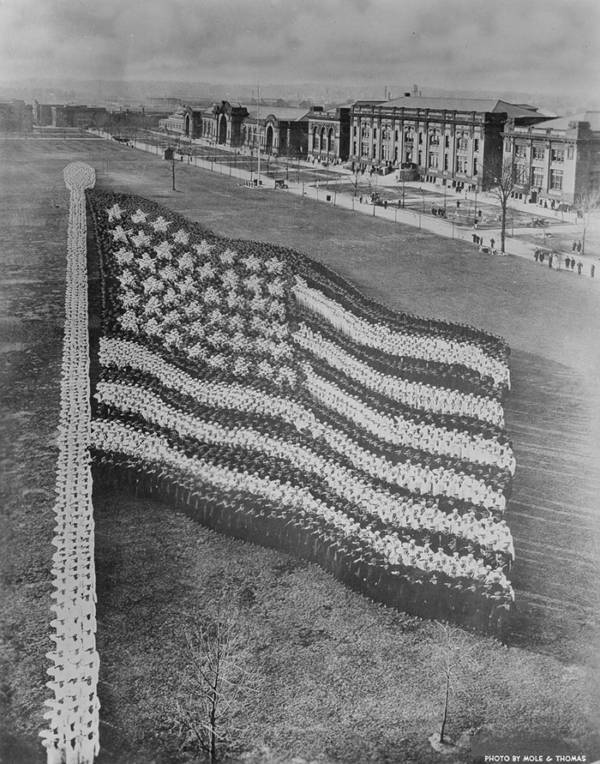

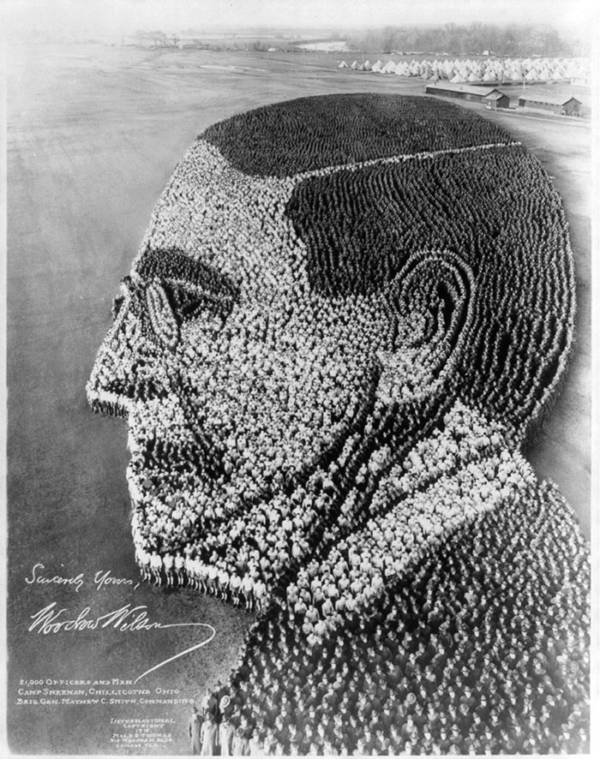

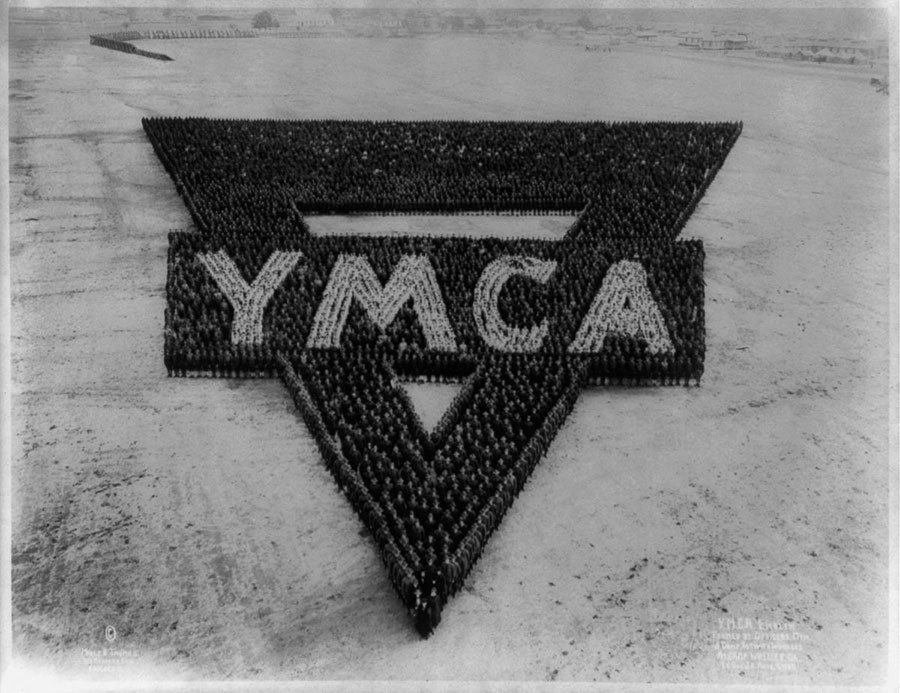

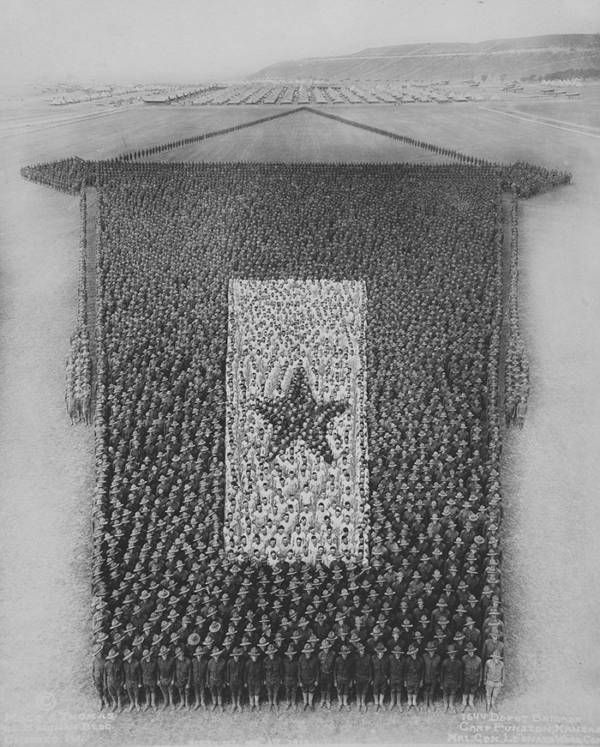

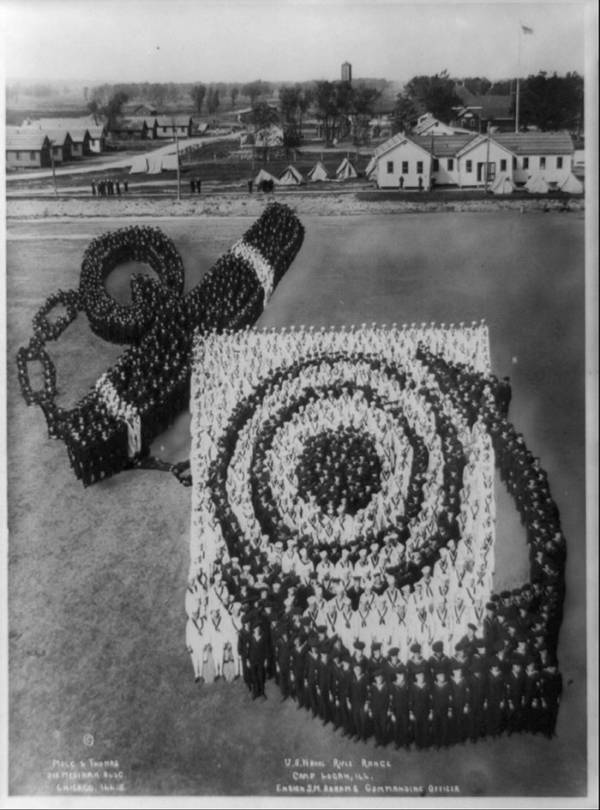

As soldiers fought in the trenches of Europe, Arthur Mole looked out to the grounds of Camp Sherman, Ohio and bellowed into a megaphone. From atop an 80-foot tower, Mole commanded a crowd of military officers to get in formation.

No, Mole was not leading a military training on this day; rather, he was attempting to bring his sketch of President Woodrow Wilson to life. The people obeyed, and soon Mole had formed a silhouette of Wilson — one made of 21,000 people.

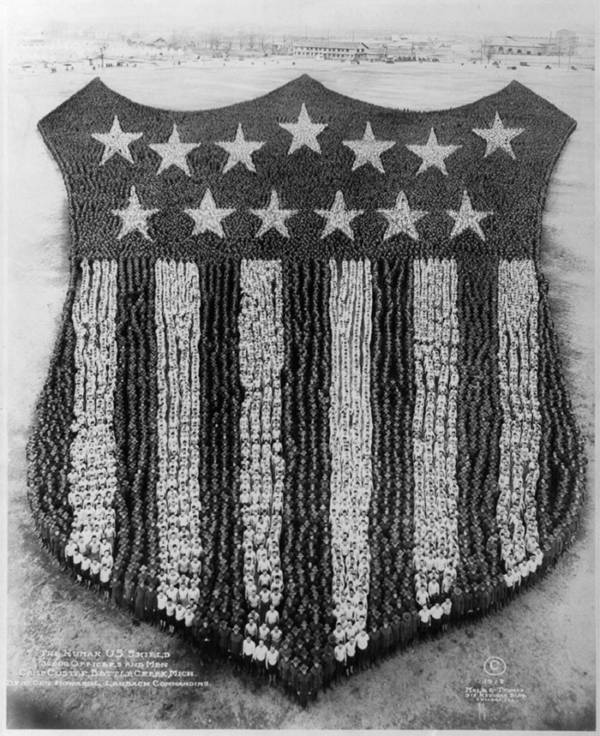

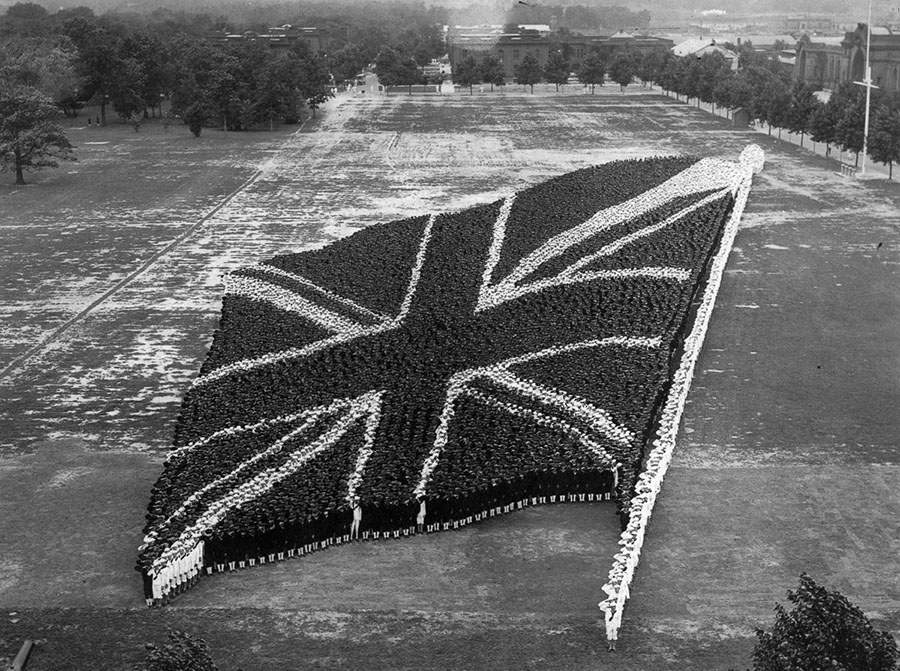

This portrait was but one of many “living photographs” Mole would make from 1917 to 1920, in an attempt to garner support for World War One.

At the onset of the war, many Americans were — along with their president — reluctant to intervene. And yet, after the Germans’ April 1917 maritime assault on commercial ships headed toward Great Britain, U.S. entry became inevitable and Wilson called on Congress to authorize a “war to end all wars.”

Congress honored Wilson’s request, and the U.S. declared war on Germany. The question remained: how to increase American support of U.S. intervention?

One such answer seemed to come vis-à-vis Mole’s living photographs. While details on funding remain murky, Mole — himself a Brit (n. 1889) — would use his mode of photography to temper anti-interventionist sentiment with living, breathing visions of the masses coming together to support the idea of the nation.

Actualizing these visions required a certain tactical precision, which Mole no doubt refined over the years. First, Mole would etch his drawing onto a glass plate, which he would then place on the lens of his 11x14 inch view camera.

Camera and drawing in tow, Mole would then climb a tower and determine the appropriate perspective to begin “developing” his living photograph. From above, Mole would call to his assistants standing on the ground and instruct them where to construct the outline. The people would then file in according to Mole’s plan, and Mole would take his photo.

The process — which would often take a week — was grueling, and the results ushered a spectacular new “type of war propaganda,” as historian Louis Kaplan notes. But to some critics, Mole’s living photographs also highlight, in a very visceral way, how faint the line between political idealism and fascism can be.

As the Guardian’s Stephen Moss writes:

“My first thought when I saw these photographs was that they were quasi-fascistic — forerunners of all those exercises in mass choreography beloved of Soviet Russia, China and North Korea, where the bodies of the masses are artfully employed to some dubious aesthetic end, notably in Olympic opening ceremonies. There is more than a hint of the Nuremberg rallies about them — could Hitler and his artificer-in-chief Albert Speer have been influenced by Mole?”

Kaplan supports Moss' appraisal. As the former writes, Mole took his photos at “a time when individual rights counted for little beside collective will, and when nationalism, the bastard son of patriotism, was metastasising into fascism.”

These days, Americans again clamor for unity and for placing the preservation of the nation above all else. Thus Mole’s photos -- and the dark endeavors these idyllic visions can catalyze and support -- warrant renewed consideration.

To see how the U.S. attempted to get more Americans on board with the war, check out this collection of World War 1 propaganda posters. Then, have a look at 31 haunting World War 1 photos.