With Europe in turmoil after World War I, German architect Herman Sörgel became convinced his Atlantropa project was the only way to prevent another conflict.

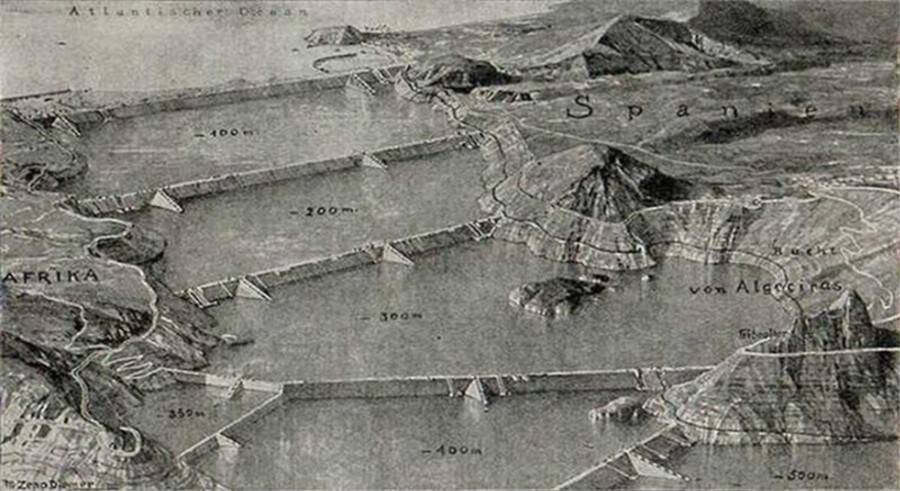

Wikimedia CommonsGerman architect Herman Sörgel proposed building a system of hydroelectric dams that would lower water levels in the Mediterranean and join Europe with Africa.

The 1920s generated brilliant ideas like penicillin and traffic lights, but the decade also spawned a number of disturbingly ambitious engineering projects. The grandest and weirdest was Atlantropa — a plan to dam the Strait of Gibraltar, producing enough electricity to power half of Europe and draining the Mediterranean to make way for human settlement in a new Euro-African supercontinent.

Although it sounds like something out of a bizarre science fiction story, this plan really existed. What’s more, a number of governments seriously considered it up until the 1950s.

This odd utopian vision started with one man and rose to international prominence — before it all fell apart.

Architect Herman Sörgel Dreams Up Panropa

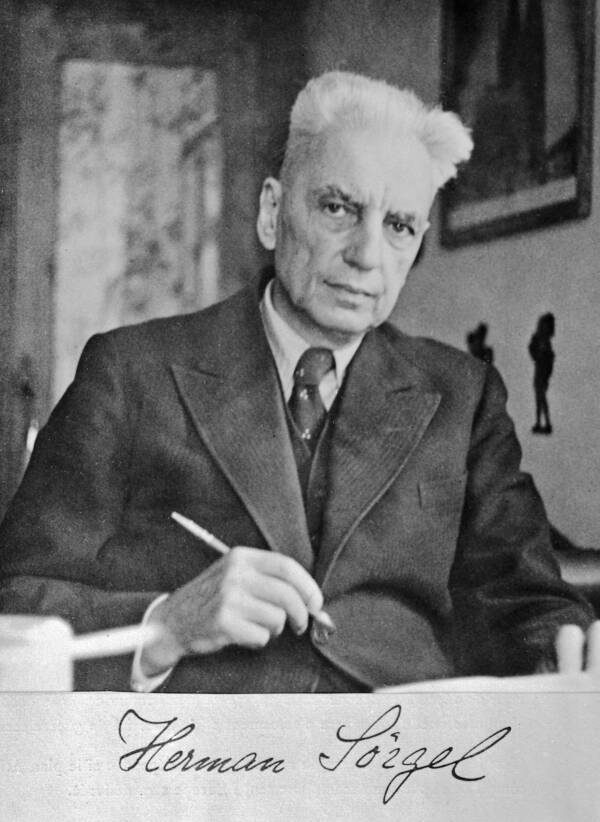

Deutsches MuseumHerman Sörgel (1885-1952), the architect of Atlantropa.

Scientists, philosophers, and engineers believed they could solve what they saw as a terminal illness in European society with grand projects. Among them was architect Herman Sörgel.

In 1927, at the age of 42, Sörgel first developed his plan for Atlantropa, which he originally called Panropa. Taking inspiration from other gigantic engineering projects like the Suez Canal, he set his sights even higher.

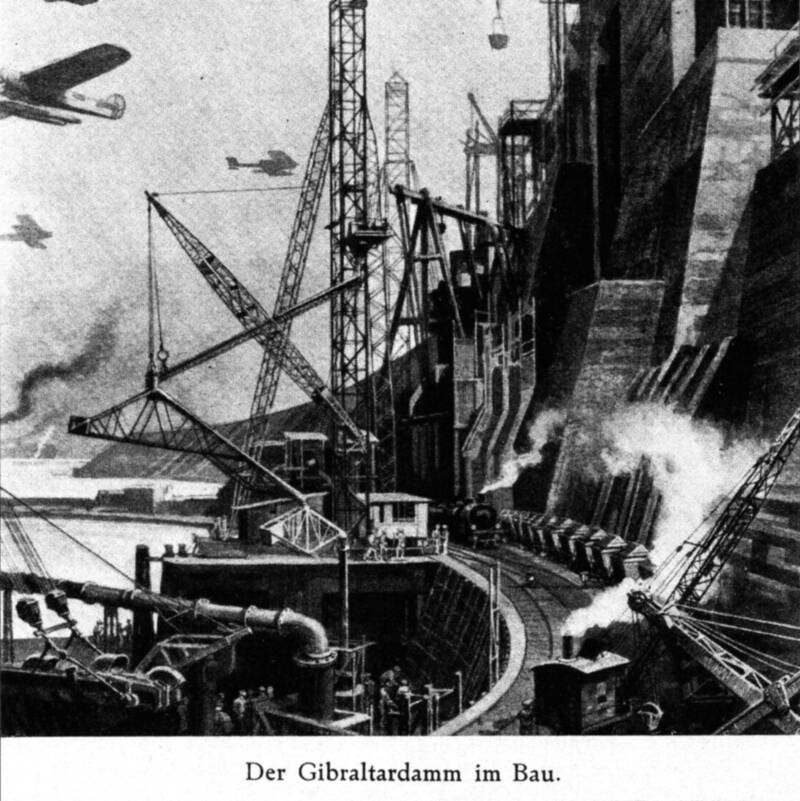

His plan for Atlantropa would build a network of dams across the Strait of Gibraltar, cutting the water level in the Mediterranean. Dams would also be placed across the Strait of Sicily, linking Italy to Tunisia. Other dams across the Dardanelles in Turkey would connect Greece with Asia.

Together, these dams would provide bridges linking Europe and Africa into a gargantuan road and rail network, tying the two continents together.

With more than 660,000 square kilometers of freshly-reclaimed land and dams churning out enough power for more than 250 million people every day, Europe would have a new golden age of plentiful electricity, abundant space, and endless supplies of food from new farmland. In Sörgel’s vision, the new supercontinent was the only way to prevent another global conflict.

Sörgel’s View Of Post-World War I Europe

Wikimedia CommonsIn this illustration from an issue of Harper’s Weekly, an angel urges European nations to defend themselves from Asia, a common trope in the racist myth of the “yellow peril.”

Still reeling from the horror of World War I, Europe struggled during this time to find hope for the future. Though Europe had suffered enormous loss of life in the war and the 1918 pandemic, its population nevertheless grew from 488 million to 534 million between 1920 and 1930.

At the same time, European politics had reached their most tense point in centuries. Nations like Poland and Yugoslavia gained independence from decades of imperial rule. And the inhabitants of the old empires feared that there was no place for them, physically, socially, or culturally.

Amid this climate, the concept of Lebensraum, or “living space,” gained increasing traction in German politics. Lebensraum was the belief that the most important thing for a society — at the time defined in terms of race — to survive and flourish was territory to provide space to its members. Of course, the idea would later be horrifically exploited by the Nazis in their quest for domination.

In densely-populated Central Europe, the desire for Lebensraum led to the conclusion that there simply wasn’t enough room. Atlantropa’s promise of expanding habitable territory seemed like the silver bullet that would solve the continent’s woes.

Atlantropa Enters The Mainstream

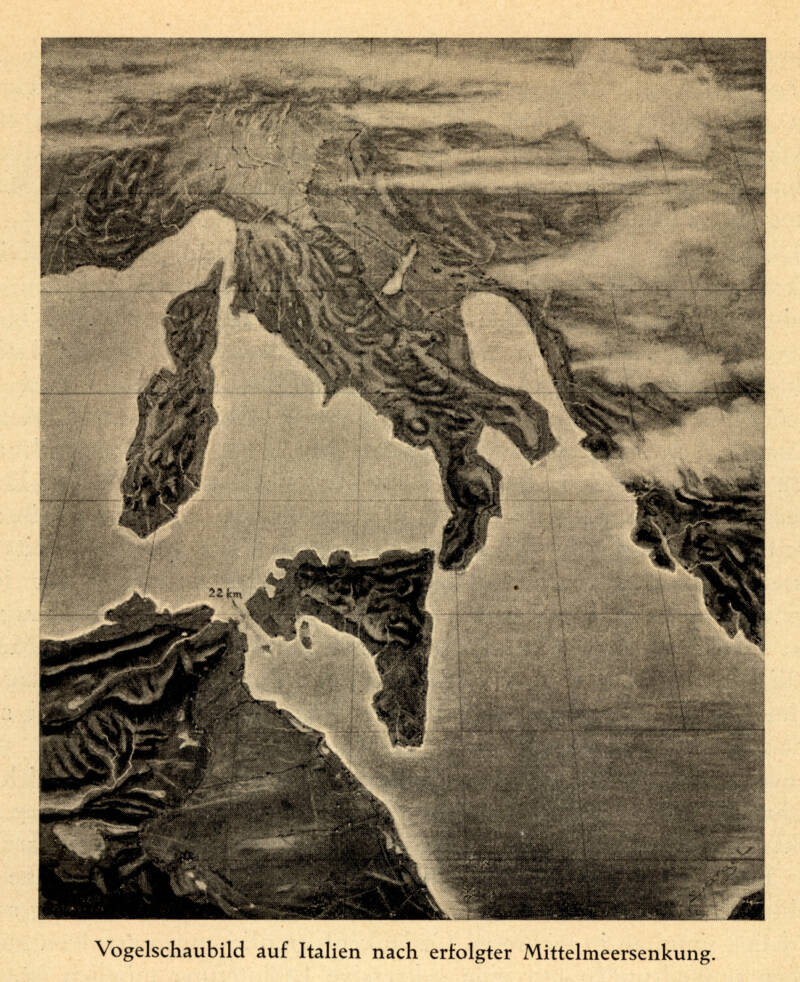

Wikimedia CommonsIn this illustration of what Italy might look like after the draining of the Mediterranean, its territory is hugely expanded, leaving Venice and other ports far inland — a prospect that made Benito Mussolini hostile to the plan.

The oddest thing about Sörgel’s plan to empty the Mediterranean isn’t its grandiosity, but the fact that it was actually taken seriously. He published a book titled Lowering the Mediterranean, Irrigating the Sahara: The Panropa Project in 1929. It quickly raised eyebrows throughout Europe and North America, attracting attention to the so-called Universallösung, or universal solution, Sörgel proposed.

After all, enormous engineering projects flourished in the 1930s, like the flooding of the Tennessee Valley, the construction of the Hoover Dam, or the digging of the Baltic-White Sea Canal in the Soviet Union. Against this backdrop, Atlantropa seemed reasonable and even exciting.

Sörgel’s madcap plan even inspired a novel called Panropa (after Sörgel’s original name for his project) in 1930. It featured a heroic German super-scientist named Dr. Maurus whose plan to drain the Mediterranean resulted in fantastic prosperity despite efforts by Asian and American villains to destroy his efforts.

Films were made about the project, too, and Sörgel formed the Atlantropa Institute out of sympathizers, financial backers, and fellow architects and engineers. For several years, the plan enjoyed a great deal of publicity in newspapers and magazines. Stories on Atlantropa often featured richly colored illustrations funded mainly by Sörgel’s wife, a successful art dealer.

Though his dream struck many Europeans as a glorious utopia, Atlantropa had a dark side which was rarely discussed in Sörgel’s lifetime.

The Racist Underpinnings Of Atlantropa

Wikimedia Commons“The Gibraltar Dam Under Construction”: the finished dam between Spain and Morocco would have been 985 feet tall.

Despite his forward-thinking vision, Herman Sörgel had a frighteningly old-fashioned view of nationality and race. Unlike his Nazi contemporaries, he believed the chief threat to Germany lay not with Jews, but in Asia. In his mind, the world should and would divide naturally into three blocs: the Americas, Asia, and Atlantropa.

With his dams in place and his bridges built, whole regions and cultures that had centered on the sea for centuries would suddenly find themselves landlocked. Redirecting the waters meant that people in other regions would lose their homes.

Part of his proposal involved blocking the Congo River and flooding Central Africa, with no thought given to the tens of millions of people who lived there. Instead, water would be redirected to the Sahara, forming vast freshwater lakes and turning the scorching desert into farmland.

In his Atlantropa, white Europeans would naturally rule as the dominant race, using black Africans as a strictly segregated source of labor.

Sörgel took his idea to the Nazis, confident they would support him. But even with the violence he intended to visit upon African peoples, his plan appeared peaceful compared to what the Nazis had in mind. Additionally his effort to turn their attention toward Africa didn’t align with Hitler’s then-goal of crushing the Soviet Union.

Sörgel spoke at the 1939 New York World’s Fair about his ideas, but without official support, he couldn’t take any action on his plans. Until the end of the war, Sörgel’s dreams of Atlantropa seemed impossible to achieve.

Postwar Interest And The Project’s Legacy

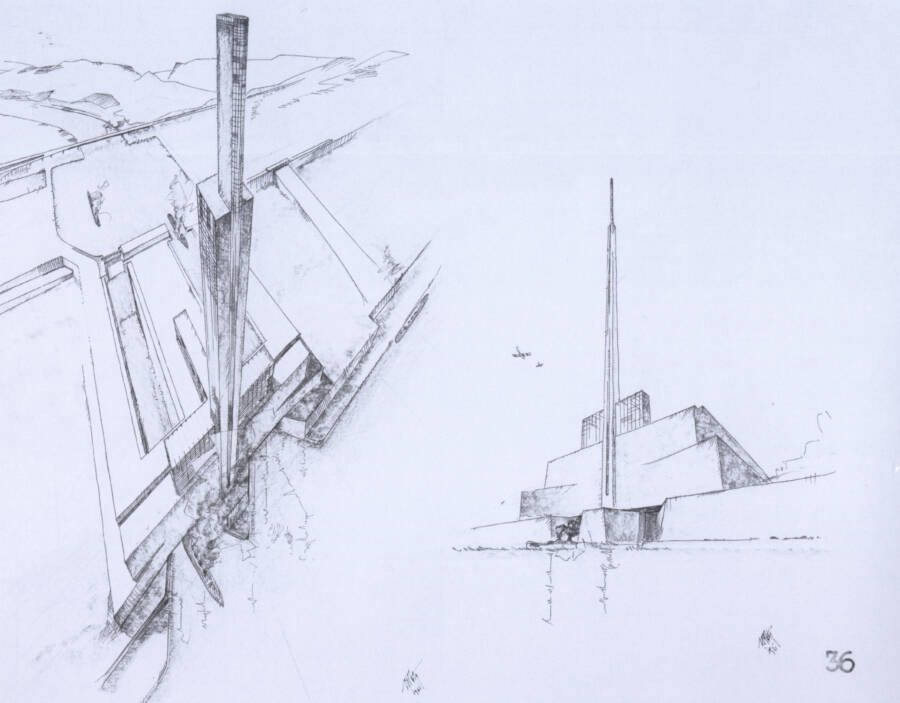

Wikimedia CommonsSketches like this one for architect Peter Behrens’ 400 meter high “Atlantropa Tower” were as far as the idea ever got, with atomic power quickly making the damming proposal obsolete.

After the dust of World War II had settled, Sörgel found himself in a continent awash with hope. The defeat of fascism and the rise of atomic power promised a bright future of ease and plenty, and he quickly got to work promoting his ideas again.

Atlantropa attracted interest from numerous politicians and industrialists, but even after the Nazis’ downfall, Sörgel refused to retract the racist elements of his vision. On top of that, the world was moving in a more practical direction. Jean Monnet’s European Coal and Steel Community formed during this time, and it would one day become the European Union.

But the nuclear reactor signaled the end for Atlantropa. At last, Europe had access to enormous sources of energy in a far more practical package than a monstrous dam network. With hydroelectric power left in the past, Sörgel’s utopian dream would never be built.

By the end of his life, Sörgel had written four more books, published thousands of articles, and given countless lectures to promote his dream. Though he worked so tirelessly to promote Atlantropa, the idea would largely die with him.

On the evening of December 4, 1952, Sörgel was riding his bicycle to Munich university for a lecture when an unknown driver hit and killed him. In 1960, the Atlantropa Institute shut its doors for good.

Since his death, Atlantropa has been relegated to the realm of science fiction. Phillip K. Dick’s alternate history The Man in the High Castle depicts a world in which Axis powers won World War II and dammed the Mediterranean. Likewise, Gene Roddenberry’s novelization of Star Trek has Captain Kirk standing on a dam in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Though the plan will likely never come to fruition, it remains too weird to be forgotten.

After learning about Atlantropa, have a look at Hitler’s pet project, a megacity called “Welthauptstadt Germania.” Then, read about a modern equivalent to Atlantropa in NASA’s plan to make Mars habitable.