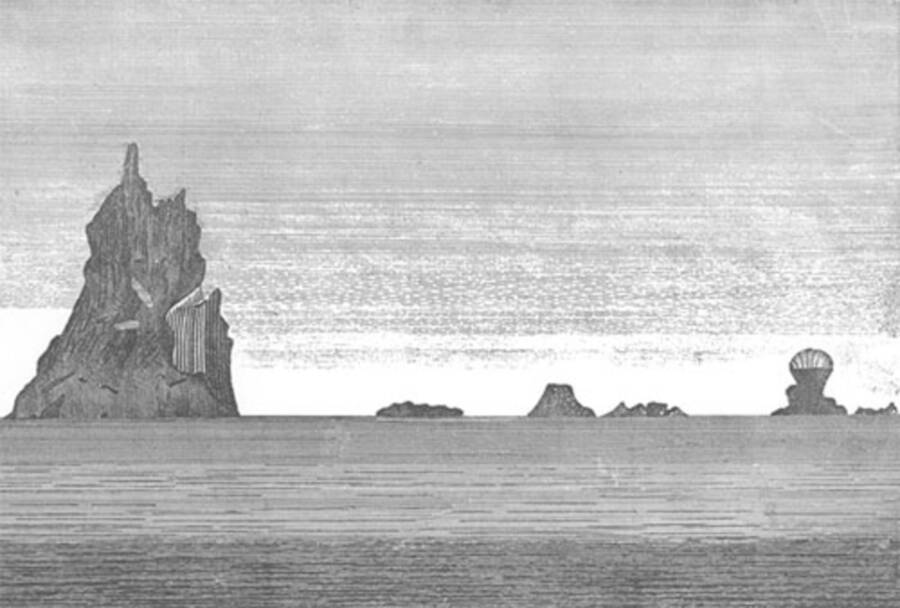

Located off the coast of Lord Howe Island between New Zealand and Australia, Ball's Pyramid is, at 1,877 feet tall, the tallest volcanic sea stack in the world.

About 12 miles southeast of Lord Howe Island, a 1,877-foot basalt monolith juts out of the Tasman Sea. This uninhabited, solitary sentinel is known as Ball's Pyramid, an intimidating and jagged structure that has captivated explorers, scientists, and adventurers for centuries.

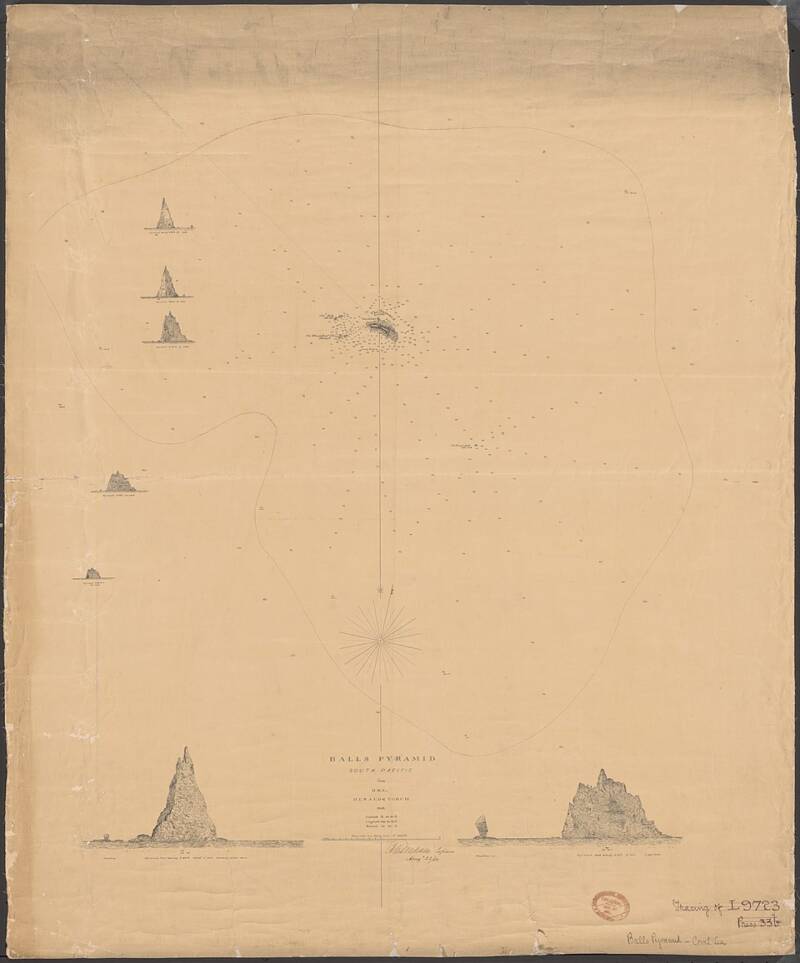

Ball's Pyramid is the tallest volcanic stack in the world, the remnant of a shield volcano based on the Lord Howe Rise, part of the submerged continent of Zealandia. It was named after the Royal Navy Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball, who first reported the discovery in 1788 — though it would be many decades before anyone reached the pyramid's summit.

That moment came on Valentine's Day 1965, when a team of explorers from the Sydney Rock Climbing Club braved the treacherous, shark-infested waters to conquer the so-far unconquerable pyramid. However, their journey was hardly the end of the story. Since then, various discoveries made on Ball's Pyramid have reignited scientific curiosity in the natural phenomenon.

The Geological History Of Ball's Pyramid

Roughly 6.4 million years ago, a massive shield volcano erupted from the ocean floor, forming what is known today as the Lord Howe Island Group. As the University of Wollongong's Colin Woodroffe clarified, however, Ball's Pyramid is not merely a separate entity but rather the erosional remnant of a much larger volcanic plug, the hardened core of a magma chamber that once fed the ancient volcano.

Over millions of years, the relentless forces of wind, rain, and the powerful Tasman Sea gnawed away at the softer outer layers of the volcano, leaving behind only the resistant, solidified magma core in a process known as differential erosion. The end result was the towering spire seen today.

Wikimedia CommonsA 1853 chart describing Ball's Pyramid.

Ball's Pyramid is uniquely composed of basaltic rock, characterized by a dark color and fine-grained texture, which has proven to be remarkably durable over the millennia. The most striking feature of the pyramid is, of course, its near-vertical spires jutting 1,877 feet into the air, which, from certain angles, can give the impression of incredibly sharp, blade-like structures.

Given its height and location in the middle of the sea, it's little wonder why adventurers and scientists became so deeply fascinated with it.

The Challenge Of Conquering Ball's Pyramid

For centuries, Ball's Pyramid remained a mysterious, unconquered fortress, proving to be too difficult for even the most seasoned climbers.

The first recorded attempt to scale the pyramid came in 1964, with a team led by Australian adventurer Dick Smith. Despite the team's valiant efforts, they were forced to abandon the ascent partway through due to treacherous conditions and a depletion of their supplies.

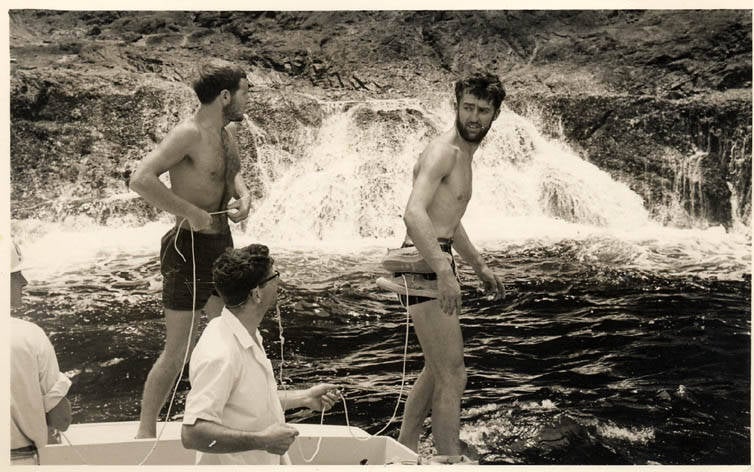

Dick MorrisMembers from the 1965 climbing expedition to reach the summit of Ball's Pyramid.

Just one year later, however, a team of climbers from the Sydney Rock Climbing Club, led by Bryden Allen, made their own attempt. A chronicle of their journey from Allen's homepage, sharing Ben Sandiland's report, can still be found online via the Internet Archive:

"Bryden had extensive experience rock climbing on the coast of Cornwall, where the pitches start straight from the sea. On the Sydney sea-cliffs and on the volcanic rock around the Kiama blowhole, he drilled us in the technique of choosing a vertical site where the swell will not rake you over the rock but instead moves vertically up and down, of waiting for a lull in the waves, and of looking underwater for holds to use once the swell leaves you on the rock."

Thanks to Allen's guidance, the crew successfully reached the summit of Ball's Pyramid. It had not been an easy ascent — it is notoriously one of the most difficult climbs in the world. It is so difficult, in fact, that in 1986 the Lord Howe Island Board prohibited access to Ball's Pyramid.

But this rule has been relaxed in recent years. Climbers can apply for a permit, and select scientists have been allowed to explore the pyramid's unique flora and fauna.

An Insect Long Thought To Be Extinct Still Lives On Ball's Pyramid

Despite initially appearing to be barren and inhospitable, Ball's Pyramid is a surprising haven for life, particularly a unique and near mythical insect: the Lord Howe Island stick insect, Dryococelus australis. This large, flightless phasmid, sometimes referred to as a "tree lobster" due to its robust exoskeleton and nocturnal habits, was once common on Lord Howe Island.

However, according to the Sydney Morning Herald, the accidental introduction of black rats to the island in 1918 quickly drove the insect to extinction — or so researchers thought.

During the 1964 expedition to Ball's Pyramid, climber Dave Roots returned with a photograph of a dead phasmid. Five years later, climber Jim Smith recovered two phasmid exoskeletons from the rock. Both of these instances proved that the "extinct" phasmid was still seemingly alive on the pyramid. But scientists would have to wait more than 40 years before they saw a living specimen with their own eyes.

In 2001, researchers found a colony of phasmids living in a melaleuca bush on the pyramid, and two years later a pair of the insects were taken to the Melbourne Zoo to start a breeding program for the critically endangered species. They were a true "Lazarus species," and the discovery sent shockwaves through the scientific community.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Lord Howe Island stick insect, once thought to be extinct, still survives on Ball's Pyramid.

The precise mechanisms by which the stick insects survived on Ball's Pyramid remain a subject of ongoing research. It is believed they subsist primarily on the sparse vegetation found in crevices and on ledges, particularly the tea tree (Melaleuca howeana). In any case, it was a precarious existence — one deserving of study.

So, in 2017, a team from the Australian Museum received permission to ascend Ball's Pyramid and study the creatures for themselves. Over three months, 30 scientists documented native fauna and took samples.

"Explorations to discover new things have driven museums for centuries," said expedition leader Paul Flemons. "Humans are driven by exploration. Ball's Pyramid is unexplored, unknown. There are not many places left in the world that have treasures like it has."

Conservation Efforts And Ongoing Study

Beyond the stick insect, Ball's Pyramid also provides a crucial nesting site for several species of seabirds, including various shearwaters, terns, and gannets. These birds find refuge on its ledges and in its crannies, where they are safe from terrestrial predators. Because of all of this, conservation of Ball's Pyramid has become a major point of focus for scientists around the world, primarily when it comes to protecting the stick insect population and the ongoing efforts to eradicate rats from Lord Howe Island.

Furthermore, the remote and exposed nature of Ball's Pyramid means it is constantly under threat from the erosive power of the ocean and the potential impacts of climate change. Rising sea levels and increased storm intensity could further accelerate erosion and threaten the precarious habitats on its slopes. Ongoing monitoring and research are essential to understand and mitigate these threats.

"There is this world of nature and we are really just part of its endless cycle," said expedition member Vanessa Wills. "Ball's Pyramid will one day fall into the ocean. Everyone lives and everyone dies, so you have to come up with some purpose in life. This trip felt like it had a purpose."

Pay a virtual visit to Ball's Pyramid, the tallest volcanic sea stack in the world, in the gallery above.

After reading about the fascinating history and ecosystem of Ball's Pyramid, read about Thor's Well, the stunning sea cave that looks like it is draining the ocean. Then, see our collection of stunning nature photographs that will make you marvel at the beauty of our planet.