How the great naval clash at 1942's Battle of Midway allowed the U.S. and the Allies to eventually beat the Japanese in World War II's Pacific Theater.

WikipediaThe U.S. Carrier Yorktown at the Battle of Midway.

By early 1942 the Japanese Empire was racking up victory after victory. After the devastating attack against the American fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japan had gone on to invade southeast Asia, the Philippines, New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies. Japanese forces now threatened British India as well as Australia.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Navy’s Commander and Chief of the Pacific Areas recalled: “From the time the Japanese dropped those bombs on December 7, until at least two months later, there was hardly a day passed that the situation did not get more chaotic and confused and appear more hopeless.”

But the tide of war was about to turn over a seemingly insignificant 25.6 square mile atoll in the middle of the Pacific called Midway.

Fear From the Skies

Wikimedia CommonsThe attack on Pearl Harbor

Despite their run of victories, the Japanese military feared that the Allies could strike back directly at the Japanese home islands.

This had a basis in reality which was proved by the audacious air raid of Jimmy Doolittle on April 18, 1942 when a squadron of bombers launched from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet some 640 miles from Japan dropped bombs on Tokyo and other targets.

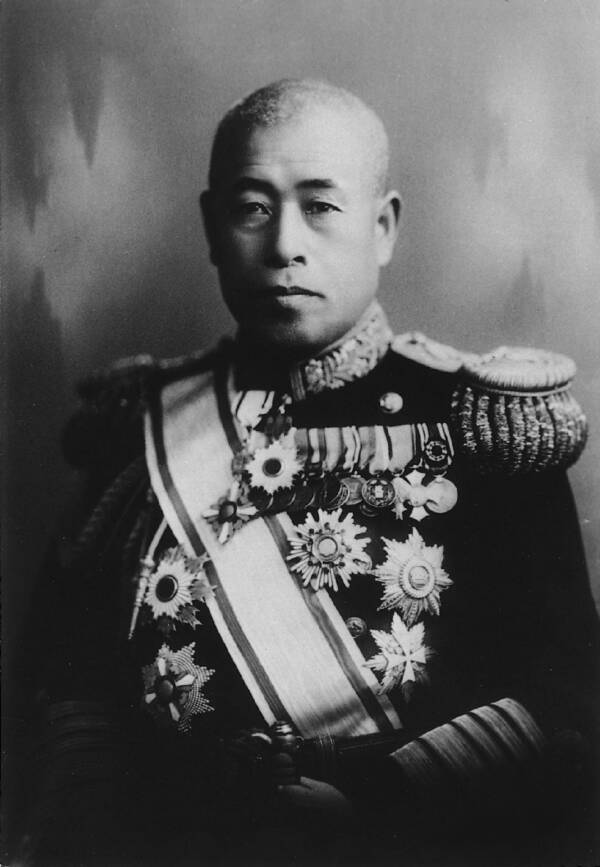

WikipediaAdmiral Isoroku Yamamoto (1884-1943)

Although the material results of the air raid were negligible, it had a larger impact on Japan’s morale and strategic thinking.

It was reasoned by Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, head of the Japanese Navy, that the American carrier force needed to be destroyed, and its forward base at Midway must be seized. This would expand the Japanese defensive perimeter and prevent carrier-based attacks on the homeland.

Strategic Midway

Wikimedia CommonsMidway Atoll with Eastern Island in foreground. Photo taken in 2011 still shows the shape of the airfield.

Midway, some 1,300 miles northwest of Honolulu is the farthest atoll west of the Hawaiian archipelago.

Being roughly halfway between North America and Asia was an ideal stepping stone for navies across the Pacific. Divided into two small islands, Eastern Island and Sand Island, it served as an important forward base for the U.S. Navy.

On Eastern Island, the U.S. Navy had three runways while Sand Island held barracks and other facilities. If the Japanese navy could control Midway, it could then easily launch more devastating attacks against Hawaii proper and thus emasculate American strength in the Pacific.

To Yamamoto’s reckoning, if Japan attacked Midway then the U.S. navy would have no choice but to defend it. It was a perfect place to stage an ambush and destroy the troublesome American carrier force.

Yamamoto’s Plan

WikipediaThe Japanese battleship Yamato

Yamamoto’s plan called for a feint attack at the Aleutian Islands. The diversion would allow a Japanese battle fleet to neutralize Midway via a surprise aerial bombardment from a fleet carrier force.

Then an amphibious landing force would take control of the island. This would lure the United States out to fight.

Yamamoto would take up the rear with a powerful force of battleships including the immense Yamato. They would sweep in to destroy the U.S. fleet when they took the bait.

It was a good plan, albeit complex, and the Japanese figured that the Americans would not be able to muster sufficient strength to seriously challenge their force since most of the American battle ships were put out of commission after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

War planners on both sides saw carriers not as the prime striking instrument in a fleet action, but rather as a supplementary harassing force since naval doctrine at the time saw battleships as the real power of the fleet.

Codes and Ciphers

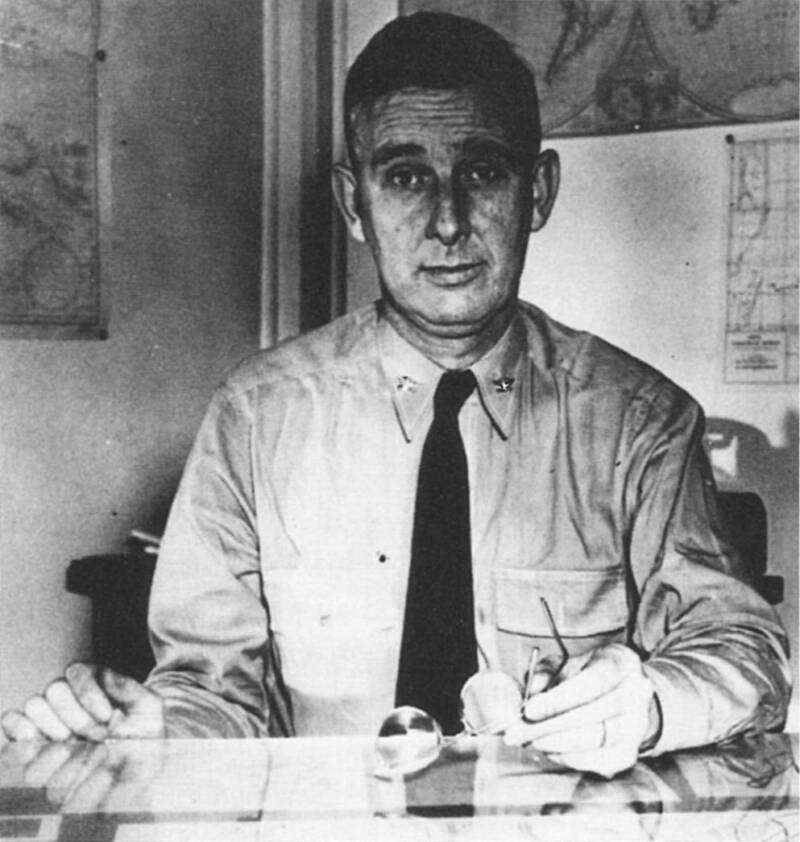

Wikimedia CommonsJoseph Rochefort (1900-1976), who identified Midway atoll as the site of the planned Japanese attack.

What the Yamamoto did not know was that an American crypto-intelligence unit called HYPO, under the leadership of Lieutenant Commander Joseph J. Rochefort, had decoded the Japanese naval code JN-25B.

Since the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. Navy had poured resources into intelligence in order to prevent another surprise attack.

It was difficult work. Cryptoanalyst Ensign Donald “Mac” Showers recalled, “There were more than 44,000 entries in the code book that made up JN25B. When we enciphered a message we would go through this dictionary of 44,000 code groups and pick out the codes for the words or phrases.” Rochefort’s team had discovered an attack imminent on what was called “AF.”

Rochefort was convinced that AF stood for Midway, but many were dubious, thinking that AF could stand for many different locations. In order to convince the brass, he staged a deception message to the Japanese claiming damage to the water supply at Midway.

They sent out the distress signal and sure enough they picked up a transmission from Japanese naval intelligence that once deciphered read: “water shortage at AF.” With that confirmation, the U.S. Navy knew the Japanese plans.

But Admiral Nimitz faced a strategic dilemma. The American fleet was outmatched by the Japanese Imperial Navy.

The U.S. Navy’s battleships lay underwater at Pearl Harbor or in repair. Of his available carriers, only two were shipshape while the third had been badly damaged. Further resources were limited because of the Allied strategic decision to concentrate on Germany first.

Nimitz could have avoided battle and waited until his carrier strength increased. He could then take Midway later which was reasonable since it was an outpost on an overextended Japanese empire. But Nimitz calculated that a battle was his to win or lose, and a win would be decisive.

Mustering for the Battle

Wikimedia CommonsAdmiral Chester Nimitz (1885-1966)

On May 26 and 27, the Japanese plan went into effect and the fleet sailed out. Meanwhile, Admiral Nimitz deployed his carriers: the USS Hornet, the USS Enterprise, and the USS Yorktown.

Of the three, the Yorktown was the least ready, having sustained damage at the Battle of Coral Sea in May 1942. While the carrier was due for a six-month overhaul, Admiral Nimitz could only afford to give it 72 hours in drydock.

On June 2, the American forces gathered approximately 350 miles northeast of Midway under the tactical command of Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher with Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance as the second senior officer.

In total there were the three aircraft carriers which supported a force of 234 aircraft. This was supplemented by 110 aircraft at Midway as well as 25 fleet submarines which were stationed about the atoll.

They waited for the Japanese strike force which consisted of four large fleet carriers with 229 aircraft and supporting ships to screen the carriers from counterattack. The Japanese carriers Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū were all a part of the force that attacked Pearl Harbor.

Overall command of the carrier fleet was given to Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. Meanwhile, Admiral Yamamoto held back his main fleet until his part of the plan came into effect.

First Engagement

U.S. Navy/Getty ImagesAmerican soldiers walk past the burning wreckage of a Japanese aircraft on Midway Airfield, Midway Island, June 1942.

At 9:00 a.m. on June 3, U.S. Navy patrol planes spotted a large Japanese force approaching, organized into five columns of cruisers, transport, and cargo ships. The Americans on Midway immediately launched nine, B-17 Flying Fortresses to intercept the Japanese fleet.

These engaged a cruiser and transport before being driven off by Japanese fighters. The first actual hit of the battle was made by a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat, which struck a Japanese oil tanker with a torpedo at 1:00 a.m. on June 4.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Fleet was on the move, sending out reconnaissance planes to probe for the location of the Japanese fleet. The Japanese did likewise, but they still did not know about the presence of the Americans. For the U.S. Navy, it was also difficult since while they knew the Japanese were there but that the B-17 attack forced the Japanese fleet to change course.

At 12:00 a.m. on June 4, Admiral Nimitz had analyzed the reports of the patrol planes and sent word to his carrier task forces of how to position themselves.

On the morning of June 4, Vice Admiral Nagumo was 240 miles northwest of Midway with his carrier strike force when he launched 108 planes – a combination of fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo bombers. In the meantime, an American patrol plane spotted two of the carriers with their escorts, “Many planes heading Midway from 320 degrees distant 150 miles!”

Midway Under Attack

Wikimedia CommonsWaldron’s TBD Devastor just prior to launch at the Battle of Midway.

The Japanese began bombing at approximately 6:30 a.m. on June 4. Fighter planes from Midway were scrambled, and 26 Wildcat aircraft took off to mount a defense of the base, 17 of which were lost in the action. Japanese hit the north side of Eastern Island and the barracks and hangar areas of Sand Island.

Damage was negligible and the Marines on Midway managed to damage or destroy a good portion of the attacking aircraft. In response, the Marine corps sent up scout bombers and torpedo bombers to go after the carriers. But they could not overcome anti-aircraft fire from the Japanese fleet.

Still, the Japanese altered course.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy carriers began launching their own strike team taking approximately one hour to launch the 117 aircraft. These proceeded on a wrong heading and were going to miss the Japanese carriers entirely.

Wikimedia CommonsDevastators on USS Enterprise.

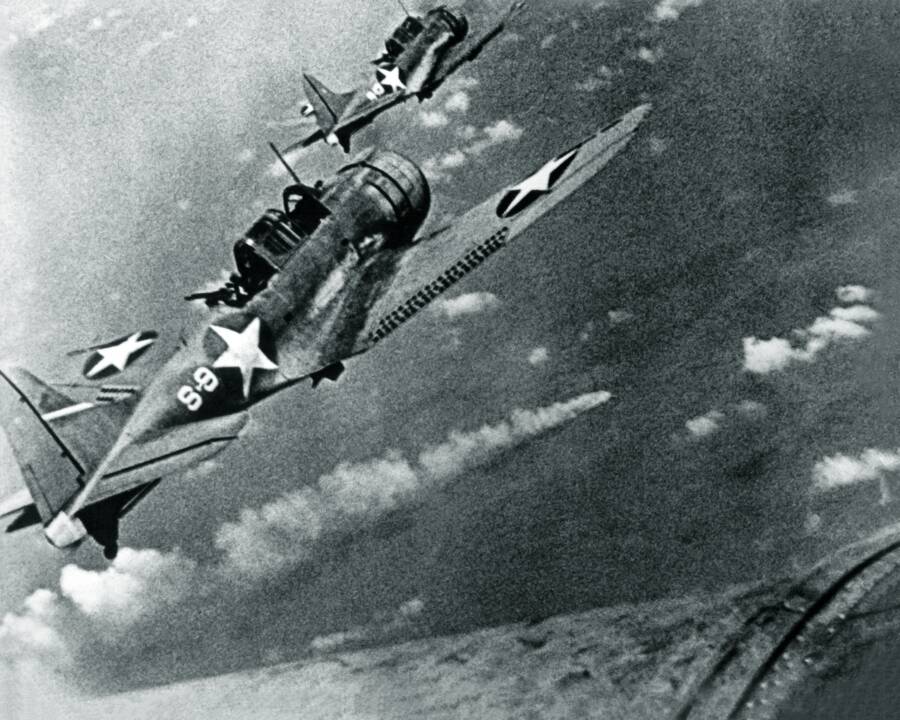

However, Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron, a squadron commander of fifteen Douglas TBD Devastators from the Hornet, disputed the heading and attempted to get the strike team to head in what he believed to be the correct direction.

When he couldn’t get them to change their heading, he broke off his 15 aircraft and proceeded on a southerly course where he found the Japanese carriers.

At about 9:30 a.m., Waldron’s squadron screamed out of the clouds. It was grim business since Waldron had no fighters to protect his dive bombers and had the complete attention of Japanese anti-aircraft measures.

It was a valiant but suicidal attack. Of the fifteen Devastators, all were shot down. Of the 30 men manning those planes, all but one were lost. However, the attack was not a complete loss since it kept the Japanese off-balance.

McClusky’s Luck

Wikimedia CommonsDauntless bombers over the cruiser Mikuma.

Meanwhile, aircraft from the Enterprise and the Yorktown were approaching. They too were having difficulty locating the target and they were running low on fuel. However, Lieutenant Commander Clarence Wade McClusky, Jr., the Air Group Commander, at 9:55 a.m. spotted the wake from a Japanese destroyer heading north to join the carriers.

He ordered all his squadrons to proceed on the heading of the destroyer. Nimitz would state that McClusky’s decision “decided the fate of our carrier task force and our forces at Midway.”

McClusky saw through his binoculars about 35 miles distant the Japanese carrier strike force. His squadron divided in two, one group to attack the Kaga and the other the Akagi.

McClusky later recalled, “I started the attack, rolling in a half-roll and coming to a steep 70 degree dive. About halfway down, anti-aircraft fire began booming around us – our approach being a complete surprise up to that point. As we neared the bomb-dropping point, another stroke of luck met our eyes. Both enemy carriers had their decks full of planes which had just returned from the attack on Midway.”

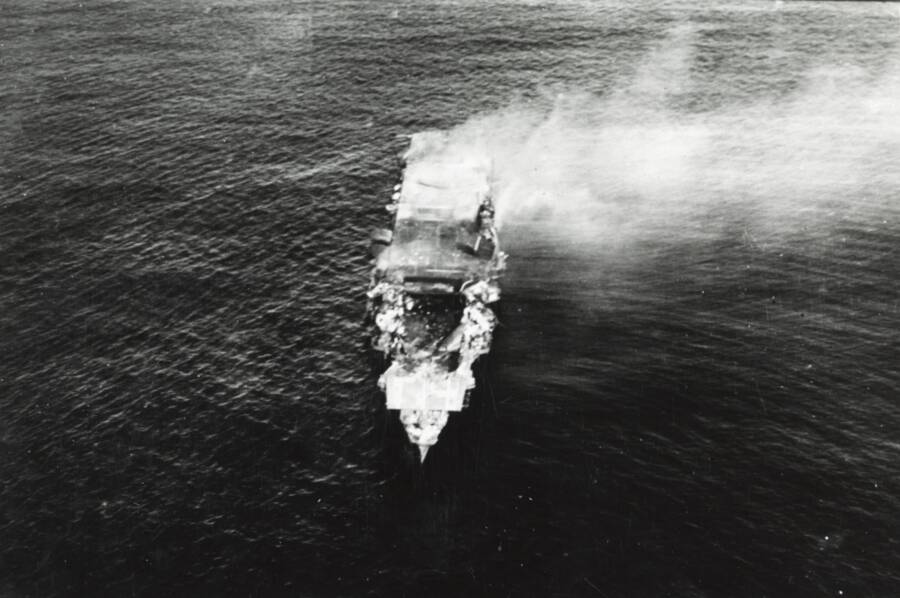

McClusky’s Dauntlesses swooped into the fray, fatally damaging the Akagi and Kaga. Meanwhile, a squadron from the Yorktown had arrived and attacked the Sōryū. Fires erupted on the decks creating severe damage.

The carrier Yorktown burning after the first attack.

One report on the attack on the Kaga described the carnage:

“There was a tremendous burst of fire near the superstructure. Pieces of the Kaga’s flight deck whirled in the air; a Zero taking off into the wind was blown into the sea; the bridge was a shambles of twisted metal, shattered glass and bodies.

“Then came three more vicious explosions, hurling planes over the side, tearing huge holes in the flight deck and starting fires which spread to the hangar deck below. Screaming sailors ran around aimlessly, trailing flames.

“Officers shouted orders against the deafening blasts. Gasoline poured from the planes’ ruptured fuel tanks, and some of the pilots who had not been lucky enough to escape the first bomb blast were cremated at their controls.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Hiryu adrift and burning on June 5, 1942.

A Japanese aviator who had help lead the attack on Pearl Harbor was aboard the Akagi. He recalled the attack:

“At that instance a lookout screamed: ‘Hell-Divers!’ I looked up to see three black enemy planes plummeting towards our ship. Some of our machine guns managed to fire a few frantic bursts at them, but it was too late.

“The plump silhouettes of the American ‘Dauntless’ dive-bombers quickly grew larger, and then a number of black objects suddenly floated eerily from their wings.

“Bombs! Down they came straight toward me!… The terrifying scream of the dive bombers reached me first, followed by the crashing explosion of a direct hit…. Looking about, I was horrified by the destruction that had been wrought in a matter of seconds.”

The smoke and flames were so intense it was impossible to count the number of times the bombers hit their targets with accuracy. All three of the Japanese carriers would eventually be abandoned and scuttled. The whole affair took between six to eight minutes and proved the decisive turning point of the battle.

Japan’s Last Blow

CORBIS/Getty ImagesA fire-fighting detail works through a pall of smoke aboard the USS Yorktown after its bombing by Japanese forces in the Battle of Midway. June 1942. | Location: aboard the USS Yorktown, Pacific Ocean, off Midway Islands.

This left one carrier left at Japan’s disposal, the Hiryū. It launched two waves of attacks at the Yorktown. The first wave managed to blow a hole in the carrier’s deck as well as destroy an anti-aircraft mount. The ship listed, taking it temporarily out of action.

Admiral Fletcher, who had been using the Yorktown as his flagship was forced to transfer his command to the heavy cruiser Astoria. The Yorktown‘s orphaned aircraft used Enterprise and Hornet‘s flattops for operations.

Scouting aircraft located the Hiryū, and the Enterprise launched a strike force against the remaining Japanese carrier in the late afternoon.

In an intense fight, the Americans were able to concentrate their air power to overcome strong defenses to land several bombs on the Hiryū setting it afire. It too was knocked out of the fight.

U.S. NavyThe Yorktown on fire.

By sundown, the U.S. Navy had achieved air supremacy at Midway and all that was left were mopping up operations.

Combat still continued until June 7 and the Japanese were able to get in one last blow. The Japanese submarine I168 torpedoed the damaged Yorktown and an accompanying destroyer. The carrier rolled over and sank.

Wikimedia CommonsCaptured survivors of the Hiryu.

Impact

In the face of the defeat at Midway, Yamamoto withdrew his main battleship force and indefinitely called off the attack. The Japanese navy, aside from losing four fleet carriers and a heavy cruiser, lost over 3,000 men. The Americans lost the Yorktown, one destroyer, and just over 300 personnel.

The Battle of Midway also demonstrated for the first time that the future of naval engagements lay with the carriers and the ordnance carried by their aircraft rather than by battleships.

The Japanese for their part made the usual propaganda claiming victory, but they knew they had lost. Nagumo’s chief of staff recollected, “I felt bitter. I felt like swearing.”

Most importantly for the course of the war, the Japanese navy was permanently weakened and their offensive deadened.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mIGXw0gse58

As naval historian Craig L. Symonds writes in his study of the battle: “The Japanese thrust was turned back. Though the war had three more years to run, the Imperial Japanese Navy would never again initiate a strategic offensive…. The war had turned.”

Yet the most pithy and famous statement of the battle is from Walter Lord’s Incredible Victory whose assessment has been inscribed on the National World War II Memorial: “They had no right to win, yet they did, and in doing so they changed the course of a war.”

The Battle of Midway and its intense action has become engraved into American popular memory as much as Pearl Harbor. In fact, its juxtaposition with the defeat at Pearl versus the heady turn of the war has been the subject of numerous books, documentaries, video games, and movies with the latest one in 2019, Midway, which stars Woody Harrelson, Ed Skrein, and Dennis Quaid.

Now that you’re done reading about the Battle of Midway, check out the story of the Battle of Iwo Jima, one of the most deadly amphibious assaults in history, and read what Kamikaze pilots really thought about their suicide missions.