The Doolittle Raid, with 16 planes targeting six different Japanese cities, allowed the United States to rebound after its devastating losses at Pearl Harbor.

Wikimedia CommonsAircraft burning after the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor.

On December 8, 1941, the American battle fleet at Pearl Harbor was a smoldering ruin. Four battleships were sunk, 188 aircraft destroyed, and 2,403 people were killed.

Emerging from the shock of the attack, American morale was low. Blackout curtains descended across windows on West Coast cities in fear of enemy bombers.

The Japanese racked up victory after victory, taking the Philippines, Guam, and other territories with seeming ease.

After the U.S.’s string of losses the fire of revenge was lit. U.S. Sen. Arthur Vandenberg captured mood of the country: “To the enemy we answer: You have unsheathed the sword, and by it you shall die.”

That revenge came in the form of a small but mighty air raid led by Lieut. Col. James Harold Doolittle, aptly dubbed the Doolittle Raid.

Wikimedia CommonsJames H. Doolittle was a flight instructor in the U.S. during World War I. In World War II, the nation’s generals turned to him for help in dealing with Japan.

Special Aviation Project Number One

Days after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin Roosevelt called for an air strike on Japanese soil. The following month, Gen. Henry Arnold chose Jimmy Doolittle — a renowned flyer and aeronautical engineer with a PhD from MIT — to plan, prepare, and personally lead the retaliatory raid, then called “Special Aviation Project No. 1.”

The U.S.’s targets were industrial and military complexes primarily in Tokyo but also in Kobe, Nagoya, Osaka, Yokohama, and Yokosuka. The goal of the strikes was multifold.

“It was hoped that the damage done would be both material and psychological,” Doolittle said in a July 1942 interview. “Material damage was to be the destruction of specific targets with ensuing confusion and retardation of production.”

The Americans also hoped the Japanese would be scared into “recalling…combat equipment from other theaters for home defense,” thus clearing the way for the U.S. to takeover islands and territories in the Pacific.

He also hoped the raid would spur “the development of a fear complex in Japan, improved relationships with our Allies, and a favorable reaction on the American people.”

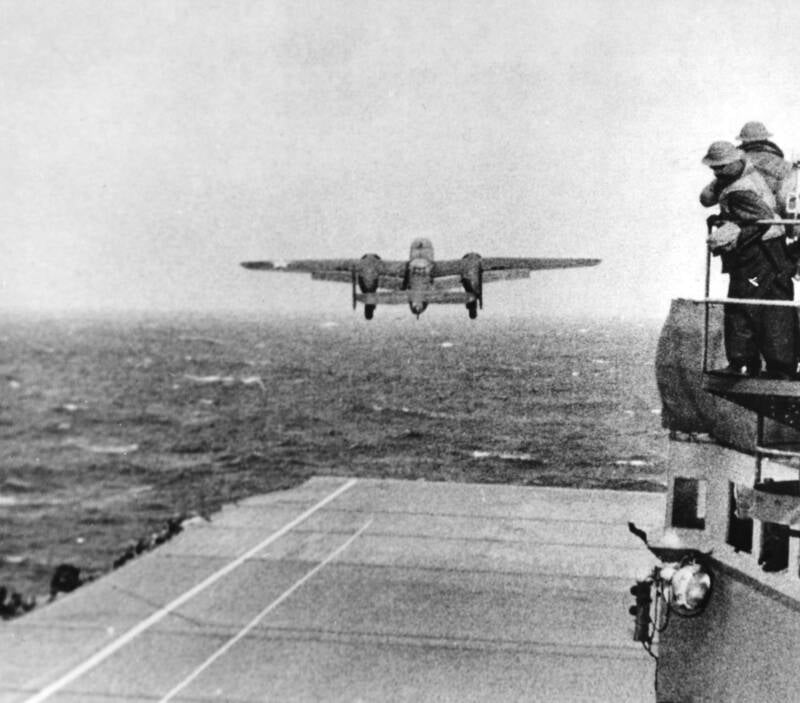

To do the job, Doolittle needed bomber planes that could lift off from an aircraft carrier, since the U.S.’s Pacific airstrips in Hawaii were too far from Japan.

He settled on the B-25 Mitchell, a no-frills bomber that required a crew of only five men. It was a nimble aircraft with a long range, but Doolittle and the crew at Ohio’s Wright Field still had to retrofit it to carry more than 1,100 gallons of fuel. Thankfully, the crew were still allowed to smoke at high altitudes.

The B-25 planes could take off from an aircraft carrier just fine, but they couldn’t reliably land on one.

And so Doolittle’s plans changed: Instead of circling back to land on the USS Hornet after dropping bombs on Japanese soil, the U.S.’s B-25s would continue eastward to China, which allowed the Americans use its coastal airstrips.

Wikimedia CommonsJames Doolittle wiring a Japanese medal onto a 500-pound bomb prior to the raid on Japan.

Training

Eighty men relatively inexperienced in the ways of wartime flying volunteered to crew the 16 planes of the Doolittle Raid, including Doolittle himself.

The airmen received their training at Eglin Field, Florida. One of the most important things they learned was how to launch a bomber into the air with only the 300 feet provided by the Hornet’s flattop.

The airmen also practiced night flying, cross-country flying, and navigating with minimal references. Doolittle trained his men as best he could to only attack military targets in order to avoid Japanese accusations of indiscriminate bombing.

On the lighter side, they had the opportunity to give their bombers such names as Fickle Finger of Fate, TNT, Avenger, Bat out of Hell, Green Hornet, and Hari Kari-er.

National Museum of the United States Air ForceA B-25 bomber on its way to take part in the Doolittle Raid, the first U.S. air raid on Japan.

The Doolittle Raid

In order to maximize the effective range of the bombers, the Hornet crept as far into the Western Pacific as it could, departing from the Alameda Naval Air Station near San Francisco on April 2, 1942.

About two weeks later, on April 18, 1942 — earlier than expected, as the Japanese had detected the Americans’ presence in the Pacific — the strike launched and by 9:19 a.m. all the planes were bound for Tokyo. About six hours later, or noon in Japanese local time, the bombers reached Japanese airspace.

Wikimedia CommonsThe USS Hornet carries 16 planes across the Pacific for the Doolittle Raid on Japan. April 1942.

Doolittle’s raiders slipped through and proceeded with their mission. The only resistance was poorly-aimed anti-aircraft fire and some fighters — none of which managed to take out even one of the B-25s.

The raiders aimed for 10 military targets in Tokyo, two in Yokohama, and one in each of the remaining cities, errantly hitting schools and homes in the process.

Eighty-seven died — some from burning to death in their own homes — and another 151 were seriously injured, including civilians and children. The raid destroyed 112 buildings and damaged another 53.

In addition to some homes and schools, the raiders destroyed a transformer station in Tokyo, crucial for Japan’s communications, as well as dozens of factories. They also hit a Japanese army hospital. Gen. Hideki Tōjō himself could see the face of one of the bombers.

“It is quite impossible to bomb a military objective that has civilian residences near it without danger of harming the civilian residences as well,” Doolittle said. “That is a hazard of war.”

The Japanese were as surprised as the Americans had been at Pearl Harbor. However, where the Japanese had managed to land a severe military blow in Hawaii, Doolittle’s Tokyo Raid barely damaged Japan’s military-industrial complex.

Wikimedia CommonsJames Doolittle sitting on the ruins of his crashed bomber after his famous raid on Japan.

The Escape

All 16 bombers and their crew slipped out of Japan, escaping over the sea toward China.

One was forced to land in the Soviet Union — which had wanted no part in the raid, as it was neutral with regards to the war against Japan — because it was so low on fuel. The Soviets interned the plane’s crew and held them until 1943, when they paid a smuggler to take them to Iran.

The remaining 75 airmen all reached China, but each one of them crash-landed, killing three.

Eight others were captured by the Japanese, four of whom died in captivity. One died of disease, and the other three were executed. The Chinese managed to help sneak the remainder out of the country and back to Allied territory.

Doolittle himself survived and returned to the U.S., where he was promoted to brigadier general and awarded the Medal of Honor for his leadership in the raid.

Public DomainDoolittle with his crew, from left: Lt. Henry Potter, navigator; Lt. Col. James Doolittle, pilot; Staff Sgt. Fred Braemer, bombardier; Lt. Richard Cole, co-pilot; and Staff Sgt. Paul Leonard, engineer/gunner.

Aftermath

The Doolittle Raid, while successful, was not a great tactical victory; Japan’s infrastructure and troops went largely unscathed.

It was, however, a strategic triumph for American morale and a blow to Japanese confidence. Japan had been exceedingly confident that their own soil couldn’t be touched; now they were proven wrong and left shaken.

The raid compelled the Japanese to enlarge their strategic perimeter, attempting to take Midway Island from the U.S. This led to a major Japanese strategic defeat and was the turning point in the Pacific Theater of World War II

WikipediaRobert L. Hite, a Doolittle Raider captured by the Japanese. He would be released at the war’s end.

The Price

The heaviest price of the Doolittle Raid was paid by the Chinese. In retaliation for assisting the Americans, the Japanese swelled their military presence in occupied China, targeting the towns that had aided the American raiders.

Beginning in June, the Japanese ravaged some 20,000 square miles in China, ransacking towns and villages, setting crops on fire, and torturing those would had helped the Americans.

“They shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved,” Father Wendelin Dunker of Ihwang wrote in his memoir. “They raped any woman from the ages of 10-65, and before burning the town they thoroughly looted it.”

According to one Chinese newspaper, the city of Nancheng — once home to 50,000 people — “became charred earth” after three days of burning.

For helping the U.S. in the small but mighty Doolittle Raid, the Chinese paid the ultimate price.

After reading about the Doolittle Raid on Japan, check out these 33 photos of the Battle of Guadalcanal, America’s first land offensive of World War II. Then, learn about the most atrocious of Japan’s war crimes.