For as long as humans have been around, we have enjoyed playing tricks on one another. Deception has always been a powerful tool, whether it was done for revenge, profit, politics or just for fun. Of course, most tricks and hoaxes are nothing to write home about. Even so, every now and then, something memorable comes along:

Berners Street Hoax

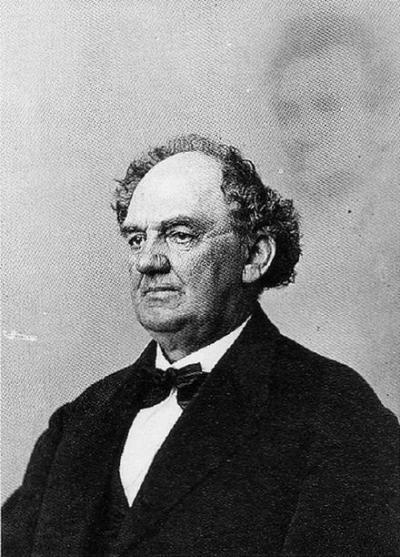

If you ever look up famous pranksters, the name Theodore Hook is bound to come up. Hook was an 18th century writer and composer but, nowadays, he is more widely renowned for perpetrating the infamous Berners Street hoax of 1810.

He does look like a rascal, doesn’t he?/caption]

Like many good stories, this one started in a bar, over a beer. Hook made a bet with a friend of his, Samuel Beazley, that he could turn any house into the most famous address in London in a week. The house in question was on 54 Berners Street, inhabited by a Mrs. Tottenham.

Hook needed a whole week in order to make preparations, but the entire “action” went down on November 27, 1810. Over the course of the week, Hook had sent out hundreds of letters in Mrs. Tottenham’s name, asking for every possible service, all of them scheduled for the same day.

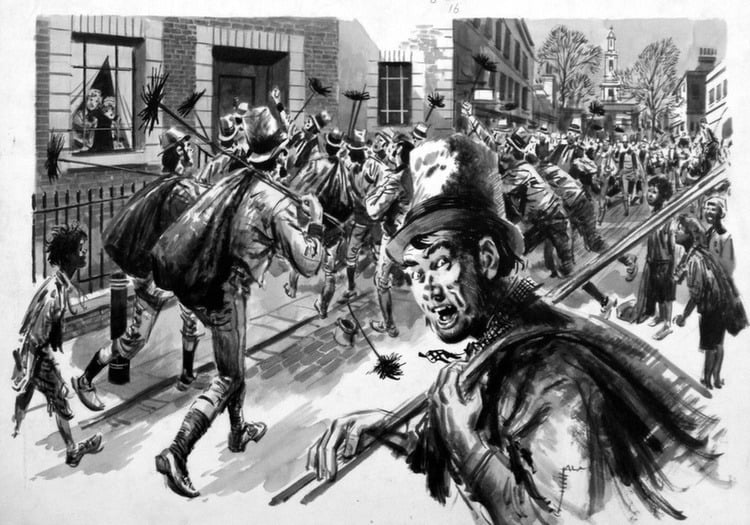

The day started off with a dozen chimney sweeps arriving at the address, followed by a coal delivery, followed by some lawyers, some priests, some doctors and even a few wedding cake deliveries. A dozen pianos also arrived, as did multiple shoemakers, painters, grocers, mercers, auctioneers, fishmongers and even an undertaker. It wasn’t long until the street became completely congested and that area of London grinded to a halt.

[caption id="attachment_35407" align="aligncenter" width="750"] Illustration of the chaos on Berners Street Source: Illustration Gallery

Illustration of the chaos on Berners Street Source: Illustration Gallery

All the commotion attracted the attention of city officials so, before long, the police had arrived, along with the Governor of the Bank of England and the Mayor of London. All this time, Hook was sitting across the street with his friend Samuel Beazley, watching the chaos unfold.

Mumler’s Spirit Photography

Spirit photography was the Instagram of the late 19th century. Like the name suggests, it involves photography that supposedly captured the images of ghosts and other apparitions. Up until William Mumler turned spirit photography into a hot commodity, the “medium” was hit-and-miss. Mumler’s ability to always produce images with ghosts made him incredibly popular. In fact, Mumler’s most iconic photo is that of Mary Todd Lincoln posing with the ghost of her deceased husband, Abraham Lincoln.

Mary Todd Lincoln with “Abraham” after his assassination.

Unsurprisingly, Mumler’s success also brought on a lot of critics, especially from within the spiritualist circle. A number of individuals raised suspicions regarding some of the “ghosts” in Mumler’s photographs. They were eventually proven correct when these “spirits” were found to still be alive, having posed for Mumler in the past.

William Mumler was taken to court for fraud. The nail in Mumler’s coffin came when P.T. Barnum, a fellow swindler who enjoyed a profitable career by working as a circus showman, produced a photograph of himself and the ghost of Honest Abe in order to show how easily these images could be forged.

Apparently, Lincoln’s ghost really liked to pose for photographs. Source: The Atlantic

Princess Caraboo

At some point in our lives, we’ve all thought about leaving our old life behind and completely reinventing ourselves. That is exactly what Mary Baker did–and she took it to the extreme. On April 3, 1817, she was found walking the roads of Gloucestershire, England completely disoriented, dressed in very peculiar clothes, and speaking an unknown language.

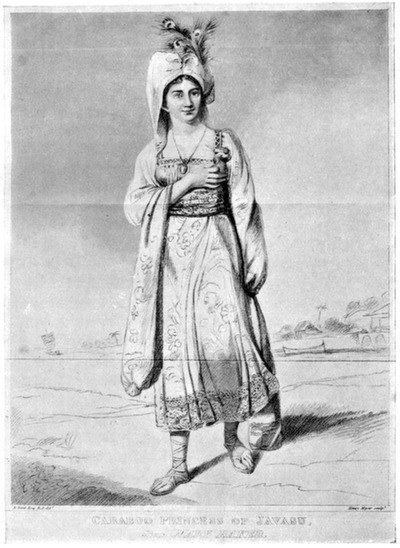

The portrait that would be her downfall. Source: Wikipedia

The only thing people could understand was that her name was Caraboo. At first, she was dismissed as a beggar from another European country, but a Portuguese sailor soon claimed to be able to translate what she said. According to him, Caraboo actually came from the island of Javasu where she was a princess. Princess Caraboo was abducted by pirates but managed to escape their ship and swam ashore.

The princess showing off her unusual garments.

Of course, this changed things. Now that people thought she was royalty, she received the royal treatment. For the next few weeks, Princess Caraboo became notorious throughout all of England and spent her time hobnobbing with the country’s elite.

She continued to display various quirky behaviors, the most infamous being her penchant for swimming naked. Unfortunately for her, all good things did indeed come to an end. A housekeeper named Mrs. Neale recognized a portrait of her from the newspaper and revealed her to be Mary Baker, daughter of a cobbler from Devon.

The Cardiff Giant

Very few hoaxes have a more intriguing, complex story than the Cardiff Giant. Found in 1869 in Cardiff, New York, this 10-foot tall statue purportedly represented a “petrified man”. In reality, New York businessman George Hull had the statue commissioned. The atheist entrepreneur was annoyed at religious scholars who claimed that giants once inhabited the world. Hull wanted to embarrass these “thinkers” and make some money in the process.

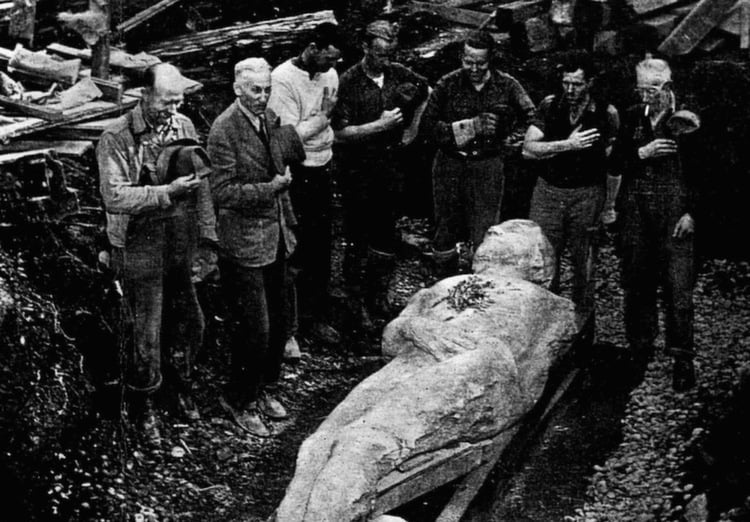

The giant being excavated.

Unsurprisingly, the Cardiff Giant was a big hit with the public.

Hull had spent around $2,600 on the creation of the statue but would make around $30,000 off it before it was all over. Various scientists examined the giant and immediately proclaimed it to be a fake. Famed paleontologist Othniel Marsh even pointed out that the statue still had clear chisel marks on it. That didn’t matter to Christian fundamentalists, who continued to attest to its authenticity.

Eventually, Hull sold the giant for $23,000 to a syndicate headed by David Hannum. They moved the exhibit to Syracuse where it still drew in a hefty profit. Eventually, the syndicate received an offer of $50,000 from circus frontman P.T. Barnum (the same man who helped end spirit photographer William Mumler’s career to a close), who was always looking for new additions to his show. His offer was declined but Barnum, ever the shrewd businessman, simply commissioned his own giant and claimed it to be the real one.

Farmer’s Museum in Cooperstown, New York – where the Cardiff Giant is today.

Barnum’s story was that the syndicate sold him the genuine Cardiff Giant and then made another one to try and scam him. The truth meant little to the public. Barnum took his giant to New York where it became a huge sensation. Before such success, Hannum sued Barnum for calling his “real” giant a fake.

By this time, Hull finally decided that enough was enough and confessed that there was never any real giant. Hannum lost the court case because the giant Barnum had been calling a fake really was a fake.

Cottingley Fairies

This story deserves some kind of award for being the world’s longest-running hoax. This one started way back in 1917, perpetrated by two young girls, Elsie and Frances, aged 16 and 9. They took five photographs of themselves in the woods, but something weird happened when these images were developed: the girls were surrounded by fairies.

Right off the bat, the girls received support from a peculiar source: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The Sherlock Holmes creator was a keen spiritualist and complete believer in fairies, so he immediately accepted the pictures as genuine despite skeptics pointing out that they were faked.

And all this without Photoshop.

Interest in the pictures of the Cottingley Fairies lasted for a few years, but eventually died down. By then, the two cousins grew up and went on with their lives. Every now and then, a newspaper would track one of the girls down and do a story on the once-famous Cottingley Fairies. The girls would again claim that the pictures are genuine and interest in the story is briefly rekindled.

By the 1970s new technology allowed careful analysis of the photographs, which had been completely dismissed as fakes. A closer look reveals a series of strings holding the fairies up. However, it wasn’t until 1983 that the girls confessed to the hoax, admitting that the fairies were nothing but cardboard cutouts from a children’s book.