Cpl. Waverly Woodson: The Black Hero Who Saved Countless Men On D-Day

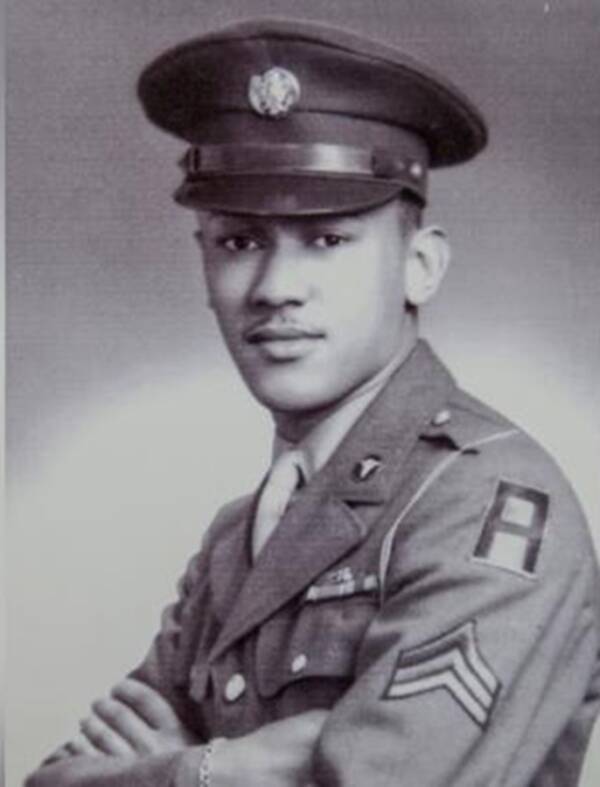

Courtesy of the Woodson familyCpl. Waverly B. Woodson Jr. spent 30 hours treating wounded soldiers and saving drowning troops at Normandy.

In the early hours of June 6, 1944, a Black medical officer named Waverly Woodson Jr. landed with his unit on Omaha Beach in France in the middle of World War II. He was part of a historic military invasion orchestrated by Allied troops that would effectively end the war, now known as D-Day.

But Woodson’s unit was unique. He belonged to the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only all-Black unit that landed on Omaha Beach that day.

By the time his unit reached the D-Day site, Woodson had already suffered a number of wounds and had pieces of shrapnel in his inner thigh and rear. Still, he persevered and went straight to work tending to injured troops on the beach.

Waverly Woodson Jr. pulled out bullets and patched up wounds. He dispensed blood plasma and performed an emergency foot amputation. He even saved several soldiers from drowning offshore.

In the end, he spent 30 hours saving the lives of countless troops on the beach — all while enduring the pain from his own injuries. Eventually, he collapsed from his wounds.

It was reported that his higher-ups had recommended Woodson to receive a Medal of Honor for his brave actions on D-Day while his commanding officer recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross.

He was ultimately awarded a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. Many believe that he was denied the highest honor because he was Black — as was the case for many other Black soldiers who served valiantly in the Second World War.

But the discrimination that Waverly Woodson Jr. faced went beyond the lost recognition. According to his widow, Joann, he was rejected as a medical army instructor at an army base in Georgia during the Korean War.

“When he got there that’s when they discovered he was a Black man. And then it was decided there’s no way he could be a Black instructor in the South at the time,” she said. “He was then sent to work at [Walter Reed National Military Medical Center].”

U.S. Maritime Commission/Library of Congress

His unit was the only all-Black battalion that was dispatched to Omaha Beach on D-Day.

After his military service, Woodson went on to work in clinical pathology for 38 years at the National Institute of Health. His specialized interest was in the practice of open-heart surgery. He died before he could receive proper honors in 2005.

Since his passing, a bipartisan group of Congress members has been working with his widow to have the late army medic recognized with a posthumous Medal of Honor.

“Cpl. Waverly Woodson never received the Medal of Honor for his outstanding courage and bravery at the Battle of Normandy where he saved many of his soldiers, and he was denied that Medal of Honor because of the color of his skin,” said U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen, one of the primary sponsors of the proposal.

The campaign to have Woodson’s military service recognized with the award has been challenging due to the lack of documentation of his service, a sadly common problem. Much of the country’s World War II archives were destroyed in a fire at the Army’s Personnel Records Center in St. Louis in 1973.

If recent efforts for the campaign to properly honor this Black hero’s legacy are successful, Joann says that she plans to donate her late husband’s Medal of Honor to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.