A botfly maggot's entire purpose is to mate, procreate, and infest mammals with its larvae.

If your worst nightmare is having your body taken over by another life form, then read no further. The botfly has a short albeit gruesome life cycle that involves infesting a host to grow its larva until it matures and pops out of the host’s flesh.

Most alarmingly, these maggot-like larvae end up inside human hosts, too.

The Botfly Is A Horrifying Parasite

Wikimedia CommonsAn adult female botfly that tries to find human hosts for its eggs.

The botfly is part of a family of flies known as Oestridae, which have a distinct trait. Like a creature straight out of a horror film, these flies lay parasitic larvae which infect warm-blooded animals, including humans. The baby larva will stay inside the host’s body until it’s mature enough to spring from the flesh of its host and continue on to the next step of its life journey.

The adult botfly — also known by other innocent-sounding names, like the warble fly, gadfly, or heel fly — can be about half an inch to an inch long, usually with dense yellow hair. They often resemble bumblebees.

Wikimedia CommonsMosquitoes act as carriers to the botfly’s tiny eggs.

Unlike bumblebees, however, there is nothing sweet about these critters, given their propensity to latch onto unsuspecting animals and become hidden parasites.

These flies can be found throughout the Americas and have a short adult lifespan of nine to 12 days. This very brief lifespan is due to the fact that adult botflies do not have functional mouthparts. Therefore, they are unable to feed and survive. Basically, they are born for no other purpose but to mate, reproduce, and die.

Their brief life allows for only a small window of opportunity to mate and lay oval, cream-colored eggs. Instead of being laid directly on a host, botfly eggs get transferred to its host through a carrier, typically a mosquito or another fly.

The female botfly starts by grabbing a mosquito in mid-air and attaching several of its own eggs onto it with a sticky glue-like substance. When they can’t find any mosquitos buzzing around, they sometimes resort to sticking their eggs onto ticks and vegetation.

When the mosquito or other carrier bug latches onto a warm-blooded animal to feed, with the botfly’s eggs in tow, the warmth from the host animal’s body causes the eggs to hatch and fall out right onto its skin.

The Weirdly Gross Life Cycle Of A Botfly

Wikimedia Commons/FlickrLeft: A cow is victim to a botfly infestation. Right: A botfly maggot emerges from its rodent host.

Once the immature botfly larva lands on the unsuspecting host, the larva will burrow beneath the host’s skin through the wound from the mosquito bite, or through hair follicles or other bodily crevices. It uses its hooked mouthparts to create a breathing hole, so it can stay alive inside its host.

The larva will stay under the flesh of the host for up to three months, all the while eating and growing, and causing increased inflammation around its excavation spot. At this stage, the larva feeds on the host body’s reaction to it, known as “exudate.” “Basically just proteins and debris that fall off of skin when you have an inflammation – dead blood cells, things like that,” medical entomologist C. Roxanne Connelly from the University of Florida explained to Wired.

Wikimedia CommonsBotfly larvae go through three instars, or molting levels, while they live inside a host’s body.

But the parasitic horror doesn’t stop there. As the botfly larva continues to munch and grow, it undergoes three stages — called “instars” — between its molts. But unlike the typical hardened shell that some reptiles and insects produce, the botfly larva’s molting has a soft texture. Ultimately, it gets mixed in with the exudate and is consumed by the larva. That’s right: the larva eats its own molting.

But believe it or not, the botfly’s parasitic life cycle is not a sinister plan to invade an animal and ultimately takeover its soul. It’s merely a survival tactic for the insect. \

“If you’re a female fly and you can get your offspring to a warm body…you’ve got a nice food source out there that you really don’t have a lot of competition for,” said Connelly. “And because [the larva] stays right there in one area, it’s not moving around. It’s not really exposed to predators.”

Even more surprisingly, botfly larvae are not lethal to their hosts. In fact, the wounds around the hole dug up by the botfly larva will heal up completely within a few days or weeks after its exit from the makeshift skin hole.

Piotr Naskrecki 2015Its larvae has little fangs and is covered in tiny spines which make them difficult to remove from the host body.

But the baby botfly’s journey into adulthood does not end there. Within hours after leaving its host, the larva turns into a puparium — a bizarre non-feeding, still cocoon-like stage of the botfly’s development. At this point, the insect has encased itself and sprouted two tufts which enable the dormant critter to breathe. The baby botfly pupates like this until finally — after two warm weeks inside its self-made cocoon — a fully-grown botfly emerges.

Horror Stories Of Human Infestations

There are various types of botflies, like the horse botfly, Gasterophilus intestinalis, or the rodent botfly, Cuterebra cuniculi, which get their names from the animals they typically choose to infest. Some species grow inside their hosts’ flesh while others grow inside their guts.

But the most dreaded botfly species of all — at least for us people — is the human botfly, referred to by its Latin name Dermatobia hominis. It is the only species of botfly known to infect human beings, though other species of flies besides the botfly have been known to cause myiasis, the medical term for insect infestations inside the body of a mammal.

The human botfly is commonly found in Central and South America, where it goes by a variety of monikers, including “torsalo,” “mucha,” and “ura.” There have been countless vacation horror stories where tourists discover lumps on their bodies, called “warbles,” where a botfly larva has burrowed inside.

Wikimedia CommonsIf a person is infested with botfly larva, the only way to get rid of it is to suffocate it then remove it by hand.

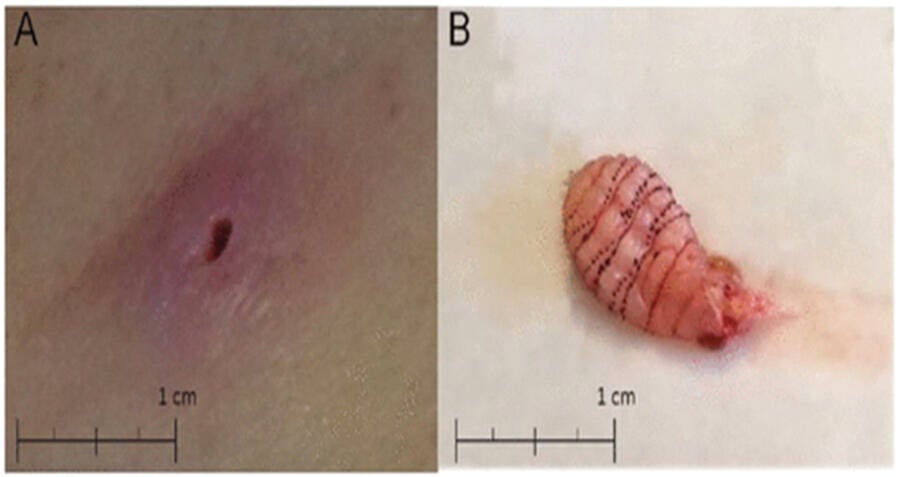

One woman who came back from her honeymoon in Belize, for example, found a skin lesion right by her groin. When it finally got itchy, she went to see a doctor. It took three different physicians to examine the lump before they finally realized it was the burrow of a botfly larva.

Another woman who returned from a trip to Argentina discovered she had a botfly larvae infestation under her scalp. Before the larvae were successfully removed — one by hand and one by surgery, after it died inside its burrow — the woman reported she could feel movements within her scalp.

If a person finds themselves infested with botfly larvae, the only remedy is to suffocate it and pull it out. People in Latin America are known to use home remedies like bacon strips, nail polish, or petroleum jelly to cover up the larva’s breathing hole. Several hours later, the larva will emerge head first, and that is when it should be immediately (and carefully) extracted using pinchers, tweezers, or — if you happen to have one handy — a suction venom extractor.

Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case ReportsSurgeons removed a botfly larva from growing lesion found on woman’s groin.

One entomologist who found a botfly larva under his scalp after a work trip to Belize thought removing the larva felt “like losing a bit of skin very suddenly.”

Another infested researcher actually let it fester until the baby botfly was ready to emerge on its own. In a twisted self-experiment, Piotr Naskrecki, who came back from a trip to Belize in 2014 and found that he had tiny parasites living inside him, decided to pop all of them out except two so that they could continue their life cycle to pupate.

Naskrecki said that he decided to go through with the horrifying home research out of curiosity and — being male — to grasp his one chance to produce another being directly from his body.

Being a researcher, of course, Naskrecki documented the entire experience on video and shared it with the public.

Wikimedia CommonsThe puparium is the final stage that the larva takes before it becomes an adult botfly.

“It was not particularly painful. In fact, I probably would have not noticed it if I had not been waiting for it, as the botfly larvae produce painkillers that make their presence as unnoticeable as possible,” Naskrecki described in the video. “It took two months for the larvae in my skin to reach the point where they were ready to emerge. The process took about 40 minutes.”

According to the scientist’s observations, while the burrowing baby he was harboring had caused inflammation around the wound, it was not infected, likely because of antibiotic secretions that the larva produced.

After the mature larva wiggled its way out of the scientist’s skin, according to Naskrecki’s observation, the wound around the hole where it had crawled out completely healed within 48 hours.

The botfly is a peculiar parasite: While it isn’t deadly, it’s deadly gross.

Now that you’ve gotten acquainted with the hideous life cycle of the botfly, take a look at these other seven scary insects that you didn’t know about. Then, learn about the Asian green hornet, the bee-decapitating species that’s the stuff of nightmares.