The Brotherhood of Eternal Love started as a pseudo-religious commune of psychedelic-loving hippies. It soon turned into a collective of California’s most wanted drug traffickers.

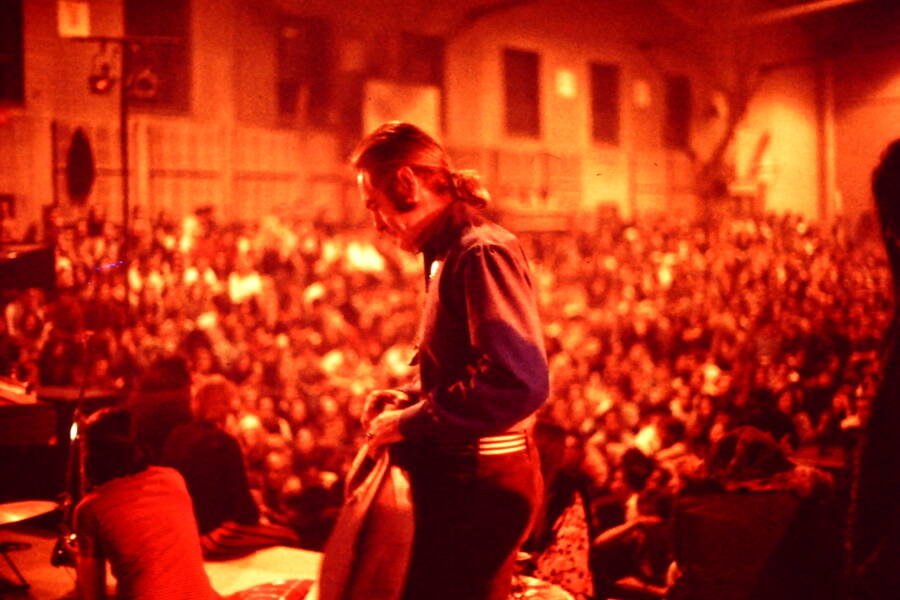

Dr. Dennis Bogdan/Wikimedia CommonsTimothy Leary, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love’s most famous member, on a lecture tour. State University of New York at Buffalo. 1969.

In 1966, John Griggs was a member of an Anaheim, California gang known as the Street Sweepers when he robbed a Hollywood producer at gunpoint, taking his LSD stash.

Griggs ingested his loot, and, by one account, soon “threw away his gun and was running around hollering, ‘This is it.'” He had a spiritual awakening, one that would lead him to found a psychedelic-inspired religious organization called the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

The Brotherhood would play a major role in the late-1960s counterculture movement — and function as one of the largest drug smuggling operations of the era.

This is the story of how one man’s trip spawned a multimillion-dollar underground drug ring.

The Brotherhood Of Eternal Love Gets Started

In William A. Kirkley’s documentary Orange Sunshine, Griggs’s wife, Carol, says that he came home from his first LSD experience determined to change the direction of his life.

He became convinced that psychedelic spirituality was the key to curing society’s ills. With his friends, he formed the Brotherhood of Eternal Love and registered it as a tax-exempt religious organization with the intention of spreading their combination of psychedelic drugs and new age spirituality.

The Brotherhood’s primary goal was to be able to distribute LSD to as many people as possible for as little money as they could manage. California officially banned the substance in October 1966, and a protest three months later in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park called the “Human Be-In” underscored the hippie resistance to the government’s infringing on their psychedelic enlightenment.

In order to finance the procurement and production of LSD, they concocted a number of schemes to smuggle in large quantities of marijuana from Mexico and hashish from Afghanistan. These efforts involved packing drugs into musical instruments, hollowed-out surfboards, film canisters, and even Volkswagen buses in order to ship their stash to the weed-craving masses of southern California.

Finding The Perfect Spot

In the beginning, the Brotherhood envisioned setting up their own society on a remote island, à la the characters in LSD advocate Aldous Huxley’s final novel, Island. In the book, a shipwrecked journalist finds himself on the fictional Polynesian island of Pala, a utopia enhanced by psychedelics.

“To us, the island represented freedom,” said Edward Padilla, an early member of the Brotherhood. The group scouted out locations in Hawaii and Micronesia — they even spoke with the King of Tonga.

Orange County ArchivesThe Brotherhood of Eternal Love ultimately set up shop in Laguna Beach in Southern California.

But their island dream would never come to be. Instead, they set up shop in Orange County’s Modjeska Canyon, where they practiced near-complete self-sufficiency. They made their own clothes, built their own houses, even delivered their own babies. Their communal dream was short-lived, however: Their compound burnt down in a fire.

As the Brotherhood found more success in their smuggling endeavors, they moved to Laguna Beach and opened an all-purpose hippie emporium named Mystic Arts World. It served as a headquarters for their drug operations as well as their spiritual practices. Starting in 1968, they began to distribute their signature product, a particularly potent variety of LSD known as Orange Sunshine, for as little as five cents a pop.

One member put it succinctly: “We weren’t greedy. We just wanted people to get high.”

As its notoriety grew, the Brotherhood attracted a variety of adherents, hangers-on, and antagonists. Three in particular would drive the group’s fame — and demise: Timothy Leary, Neil Purcell, and John Gale.

A Guru Joins

Timothy Leary was a clinical psychologist and a former Harvard University professor who, by the mid-1960s, had become an evangelist for the use of psychedelic drugs. His pioneering research as a co-founder of Harvard’s Psilocybin Project — including a prison experiment which showed that recidivism rates dropped dramatically among inmates who participated in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy – got him fired and made him an instant counterculture icon.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Brotherhood sold — and gave away for free — their very own LSD.

Early in the Brotherhood’s existence, John Griggs had traveled to Leary’s estate in New York to discuss psychedelics with him. The Brotherhood also sold copies of Leary’s book, Psychedelic Prayers, at Mystic Arts World.

In 1967, Leary moved to Laguna Beach to join the Brotherhood, seeing Griggs as someone who shared his own goals and the group as a realization of the ideas he had been preaching for years. Leary’s participation increased the prominence of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, allowing them access to hippie-inclined celebrities and rock and roll bands.

“We were totally spiritual, religious people,” said an original Brotherhood member, Robert “Stubby” Tierney. “Acid and marijuana were sacraments to us. We were so upset about Vietnam. We were like soldiers. We brought Timothy Leary to us to approach famous people like Crosby, Stills and Nash, the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane — all the San Francisco bands — so we’d have control of the music. We really had power.”

But Leary was also focused on his personal goals, perhaps more so than the goals of the group. On May 16, 1969, he announced that he was running for governor of California — against incumbent Ronald Reagan, and against the wishes of the rest of the Brotherhood. His notoriety brought greater attention from law enforcement.

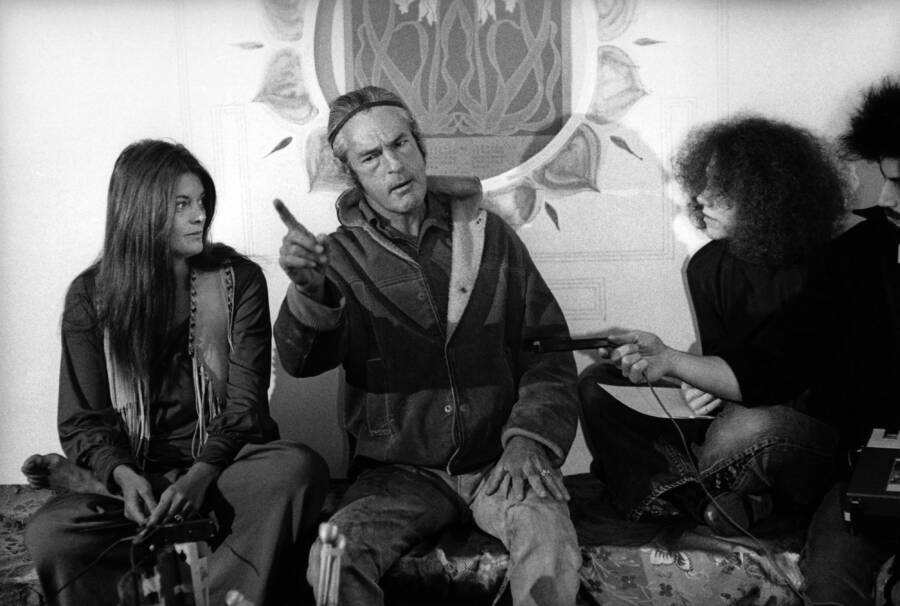

Robert Altman/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesTimothy Leary campaigns in Berkeley, California with his wife, Rosemary, as he runs for governor of California. He campaign slogan was “Join the Party.” May 30, 1969.

While the Brotherhood had drawn the ire of the local police for years — “We were the potheads in town,” said Tierney. “We were longhaired kids. The cops got on our case as a public nuisance.” — they mostly managed to avoid any trouble thanks to a combination of ingenuity, anonymity, and police incompetence.

But Leary was a celebrity and an easily identifiable target for the one Laguna Beach police officer most obsessed with taking down the Brotherhood.

The Police Get Their Man

Officer Neil Purcell had tried and failed to bust the Brotherhood of Eternal Love ever since it first moved to Laguna Beach. He was such a known quantity among the members that they had something that they called a “‘Purcell Watch,’ a whole system of alarms and whistles so everyone knew when Purcell was around.”

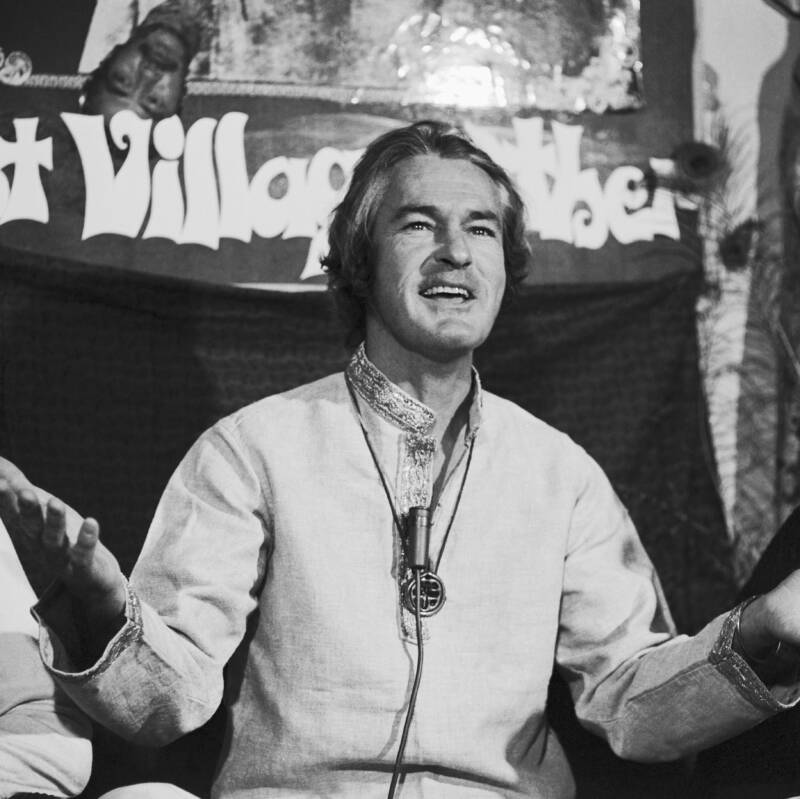

Bettmann/Getty ImagesTimothy Leary at a press conference in 1968, announcing that his group will join forces with the Black Power Organization.

Timothy Leary’s high profile made him an obvious target for Purcell. On the evening of December 26, 1968, Purcell saw people arguing in a parked station wagon. When he approached the vehicle, he recognized Leary as the driver.

By his own account, Purcell searched the vehicle and found two kilos of marijuana and hashish strewn about the cabin. As Leary remembered it, Purcell planted two joints on him. Purcell arrested Leary, who was convicted of marijuana possession and on January 21, 1970, was sentenced to 10 years in prison — plus another 10 years added on for a prior arrest in 1965.

With $25,000, the Brotherhood tried to free him. Paying the Black Panthers, who passed the money onto the Weather Underground, Leary and his wife, Rosemary, managed to be smuggled all the way to Algeria in September 1970.

Leary’s bust was devastating for the Brotherhood, which was already reeling from the 1969 death of founder John Griggs, who overdosed on psilocybin. Many of its key members, including Griggs, moved to Idyllwild Canyon, leaving the bulk of the organization’s Laguna Beach operations in the hands of John Gale.

New Leadership In Laguna Beach

John Gale joined the Brotherhood of Eternal Love relatively early in its existence. But unlike the other initial members, he was not a true believer in their psychedelic spirituality. He was a surfer and a petty criminal who seemed more attracted to the group for the danger and excitement of their escapades.

Gale was the architect of one of the Brotherhood’s most notorious stunts when he arranged to have 25,000 hits of acid dropped from an airplane on crowds gathered in Laguna Beach for a three-day “happening.”

He also had a particular talent for smuggling and selling drugs. When the majority of Brotherhood retired to a ranch near Idyllwild, Gale remained in Laguna Beach and put those talents to use.

Don Graham/FlickrTahquitz Rock in Idyllwild, California. The Brotherhood moved near here after its heyday.

Under his leadership, the Laguna Beach Brotherhood transformed from a religious organization that smuggled hash and marijuana in order to fund their psychedelic spirituality mission into a more straightforward drug operation known to police as the Hippie Mafia.

The End Of The Brotherhood Of Eternal Love

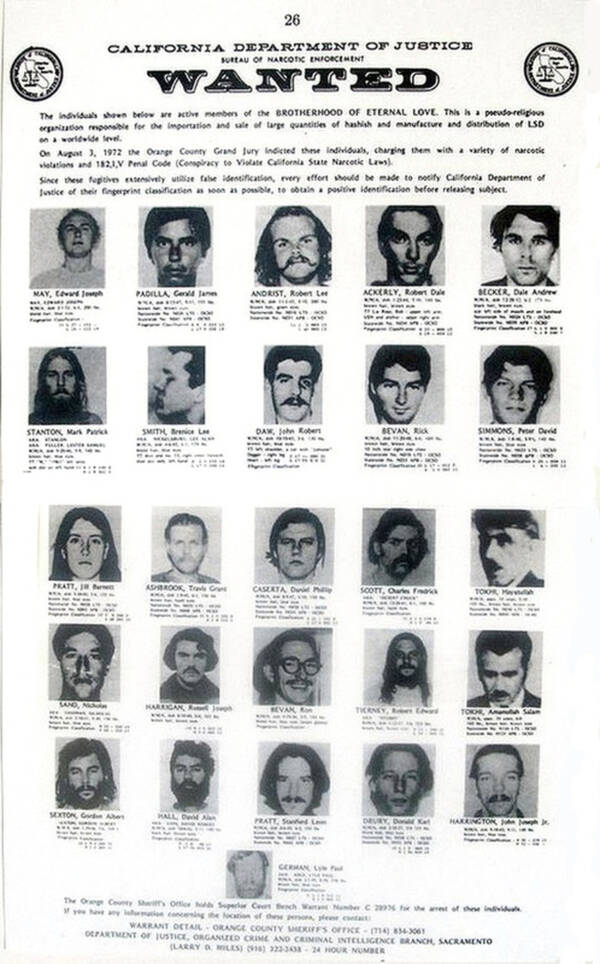

On August 5, 1972, state and federal officials conducted a series of raids on Brotherhood properties in multiple states. Some core members managed to escape and avoid capture for several years but eventually nearly dozens of members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love were arrested and convicted of various drug-related offenses.

California Department of JusticeA wanted poster for the members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. 1972.

Gale remained a major drug dealer in Laguna Beach. In 1981, he was busted with over $7 million worth of cocaine. Before he could be convicted, he was decapitated in a car accident.

By that time, cocaine had usurped LSD as the young person’s drug of choice. “Cocaine destroyed our scene,” Tierney said. “Brothers started taking opium and doing cocaine and amphetamines. That took all the spirituality out and made people selfish. We took so long to destroy the ego. We were a Brotherhood, a family beyond family. In the beginning it was really strong, and later the coke would make everyone paranoid.”

And so the Brotherhood of Eternal Love — like most of the fun-loving happenings of the 1960s — remains a fond memory.

After reading about the psychedelics sold and imbibed by the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, check out 33 photos that beautifully capture 1967’s Summer of Love. Then, read all about the trippy history of peyote, the mysterious Navajo hallucinogen.