In the second grade, Bryan Stevenson's school placed him in the slowest of three groups because he was black. Now he's a Harvard Law School graduate who's saved more than 100 people from death row.

Wikimedia CommonsBryan Stevenson speaks at the Summit on Race in America at the LBJ Presidential Library in 2019. Rising from the segregated South to Harvard Law, Stevenson founded a nonprofit that challenges poverty and racial injustice.

When a mostly-white jury convicted Walter McMillian in 1988 for the murder of a white woman in Monroeville, Alabama and recommended life in prison, a local judge overruled them and imposed the death penalty instead.

Referred to as “judge override,” the controversial practice caught the attention of attorney Bryan Stevenson, then the director of the Alabama Capital Representation Resource Center in Montgomery.

“No capital sentencing procedure in the United States has come under more criticism as unreliable, unpredictable, and arbitrary than the unique Alabama practice of permitting elected trial judges to override jury verdicts of life and impose death sentences,” proclaims the website of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization Stevenson founded.

Stevenson could clearly see that there were constitutional violations at work in McMillian’s case, but what troubled him the most is why the Alabama justice system couldn’t see it too.

Equal Justice InitiativeBryan Stevenson took on Alabama death row inmate Walter McMillian’s case in post-conviction. Stevenson’s fight to prove McMillian’s innocence is the true story behind the upcoming film, Just Mercy.

Bryan Stevenson: Born Into Segregation

Before he graduated from the hallowed halls of Harvard Law School in 1985, Bryan Stevenson was born in Nov. 14, 1959 in the aftershock of the Jim Crow South. During the Great Migration, his family had relocated to Milton, Delaware, and systemic violence against the black community quickly shaped his views on justice.

Brown v. Board of Education had officially desegregated America’s public schools in 1954, but it took some time for that decision to meaningfully reach southern Delaware. Stevenson attended a “colored” school until the second grade, and even after that his school wouldn’t let black and white kids play on the monkey bars at the same time.

His father, born and raised in southern Delaware, took the racial slights in stride, but Stevenson’s mother, a Philadelphia native, fought back. When Stevenson was automatically placed in the slowest of three second-grade groups because of the color of his skin, his mother petitioned until he was placed in the group for the most gifted.

“Don’t let people mistreat you because you’re black,” she’d tell Stevenson and his two siblings.

But as much as his family fought against the system, the system had a way of taking hold. Stevenson’s uncle died in prison, and when he was 16, robbers stabbed his 86-year-old grandfather to death in his own home.

The perpetrators received life prison sentences. Years later, Stevenson recalled that he thought the sentence was fair for the crime.

“Because my grandfather was older, his murder seemed particularly cruel,” he said. “But I came from a world where we valued redemption over revenge.”

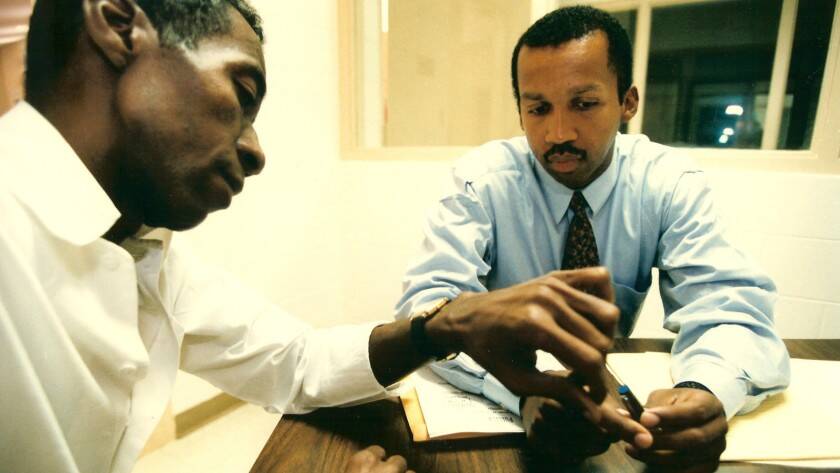

HBOAttorney Bryan Stevenson (right) of the Equal Justice Initiative during a meeting with Walter McMillian as shown in the HBO documentary True Justice.

And Stevenson’s criminal justice work reflected those values. He graduated from the most prestigious law school in the country — though he originally thought he’d be a professional pianist, and chose to go to law school as more or less an afterthought. “I didn’t understand fully what lawyers did,” he later admitted.

Still, he excelled at Harvard.

Instead of following suit with most of his classmates and working for a corporate law firm, he moved to Atlanta to work for the Southern Center for Human Rights, representing death row inmates across the South.

Soon he was director of the Alabama Capital Representation Resource Center’s office, a federally funded organization in Montgomery that provides legal defense for death row inmates.

He was still a young man when he finally met McMillian, whose case had risen to infamy in Monroeville’s black community — since the police investigation screamed of racial bias.

The Case Of Walter McMillian

Walter McMillian was a black man raised outside Monroeville, Alabama. He picked cotton before he was old enough to go to school, and in the 1970s he started his own pulpwood business. He wasn’t rich, but he was much more independent than most of the rest of the local black community — and much freer than the white people around him thought he had any right to be.

Equal Justice InitiativeAttorneys with the Equal Justice Initiative proved that witnesses testifying against Walter McMillian lied.

He’d kept a clean criminal record, save for a misdemeanor after he was dragged into a bar fight. But when his affair with a white woman became public in 1986, he felt a target drawn on his back.

Then, on Nov. 1, 1986, a white 18-year-old college student named Ronda Morrison was found dead on the floor of the dry cleaners where she worked in Monroeville. She had been shot three times.

Local police spent months investigating many different suspects for the killing, but none of their leads panned out. It wasn’t until police arrested Ralph Myers — a career criminal, compulsive liar, and the new boyfriend of McMillian’s ex – for a separate murder, that they latched onto McMillian.

“The only reason I’m here is because I had been messing around with a white lady,” McMillian told the New York Times from death row in 1993.

His case went to trial, and since the case had been all over the headlines in Monroe County, which was 40 percent black, proceedings were relocated to Baldwin County, which was 86 percent white.

There was no physical evidence linking McMillian to the crime, and six alibi witnesses said he was at a fish fry at the time of the murder. Still, the jury — 11 white jurors and one black juror — went with the prosecution and sentenced him to life in prison on Aug. 17, 1988. The trial lasted a day and a half.

Jamie Foxx as Walter McMillian in the film, Just Mercy.

Instead of abiding by the jury’s recommendation, Judge Robert E. Lee Key, Jr. utilized his state-sanctioned powers to sentence McMillian to death by electric chair. Key cited the “vicious and brutal killing of a young lady in the first full flower of adulthood” as reason for his judgement.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Alabama judges have overridden jury verdicts 112 times since 1976 (the state officially abolished the practice in 2017).

McMillian filed an appeal, but a higher court affirmed his death sentence in 1991.

And that’s when Bryan Stevenson stepped in.

“We in the African American community have always known that the criminal justice system is a threat, that it will take people who are innocent or wrongly convicted and it will treat people unfairly,” Stevenson said later in an interview with Essence magazine. “But we keep fighting.”

Stevenson Defends McMillian

The film Just Mercy, based on Bryan Stevenson’s book of the same name, focuses on his tireless pursuit of the truth in McMillian’s case, and that begins with the testimony of Ralph Myers.

Equal Justice Initiative Bryan Stevenson got Walter McMillian’s murder conviction overturned in 1993, after McMillian spent six years on death row.

With no leads on who killed the white woman in Monroeville, police saw an opportunity with Myers after they arrested him on suspicion of another murder.

During interrogation, police claimed to have eyewitnesses that could prove Myers and McMillian as murderers. So Myers lied and implicated McMillian.

Later, when Stevenson obtained the original recording of Myers’ confession, he heard Myers complaining about having to confess to crimes he and McMillian did not commit. It was the first shot of a smoking gun.

More evidence of McMillian’s innocence trickled in. After Stevenson proved that eyewitnesses who testified to seeing McMillian’s truck at the crime scene were lying, they retracted their testimonies.

Eventually, Stevenson had everything he needed to overturn McMillian’s conviction and get him a new trial — and he did just that on Feb. 23, 1993. A week later, local prosecutors dropped the charges against McMillian. For the first time in six years, he was a free man.

Financial TimesWalter McMillian (left) and Bryan Stevenson after overturning McMillian’s conviction.

“I think everybody needs to understand what happened because what happened today could happen tomorrow if we don’t learn some lessons from this,” said Bryan Stevenson on the day of the court decision.

“It was too easy for one person to come into court and frame a man for a murder he didn’t commit. It was too easy for the state to convict someone for that crime and then have him sentenced to death. And it was too hard in light of the evidence of his innocence to show this court that he should never have been here in the first place.”

Bryan Stevenson’s Work After Freeing McMillian

Walter McMillian’s exoneration put a much-needed spotlight on racial injustice in the criminal justice system, and Bryan Stevenson has dedicated his career to the cause.

My work with the poor and the incarcerated has persuaded me that the opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice.

With Stevenson at its helm, the Equal Justice Initiative has won more than 135 reversals, relief, or release from prison for people on death row, as well as relief for hundreds of other wrongfully convicted or unfairly sentenced people.

Outside of the courtroom, Steven uses his platform to push for criminal justice reform and to shed light on systemic inequalities.

In 2018, he helped open the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the first memorial dedicated to the legacy of black people who have been enslaved, lynched, or terrorized by the criminal justice system.

It’s a major complement to EJI’s Community Remembrance Project, which has documented nearly 5,000 lynchings across the U.S. and erected historical markers to commemorate them — helping ensure that America’s violently racist history will not go unforgotten.

“Everybody should know him,” said Jamie Foxx, who plays McMillian in Just Mercy. “It reminds me of when Barack Obama came along. You went, ‘Everybody should know him.'”

For his criminal justice work, Stevenson has received the prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Prize; the ABA Medal, the American Bar Association’s highest honor; and the National Medal of Liberty from the American Civil Liberties Union after a nomination by U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Stevens.

“I’ve come to understand and to believe that each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done,” said Stevenson.

“I believe that for every person on the planet. I think if somebody tells a lie, they’re not just a liar. I think if somebody takes something that doesn’t belong to them, they’re not just a thief. I think even if you kill someone, you’re not just a killer. And because of that, there’s this basic human dignity that must be respected by law.”

After reading about the remarkable life and work of attorney Bryan Stevenson, who’s saved hundreds from prison, learn all about the case of the Central Park Five, a group of non-white teenagers who were wrongfully convicted of brutally raping a white woman in the 1980s. Then, read the harrowing last words of 23 executed criminals.