Five minority teenagers known as the Central Park Five were charged with the assault and rape of Trisha Meili and spent years behind bars. But here's what really happened.

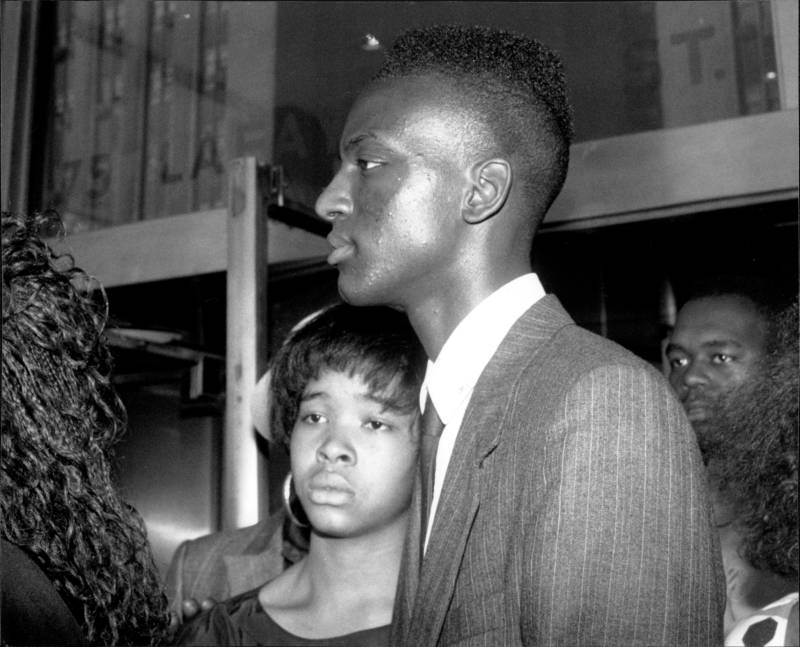

John Pedin/NY Daily News Archive/Getty ImagesKorey Wise in court for the case of the Central Park jogger. Oct. 10, 1989.

The case of Central Park jogger Trisha Meili, which ended in the conviction of “The Central Park Five,” was a prime example of not only the rampant crime in 1980s New York City but of also the rampant racism that led to the improper incarceration of these minority youths. But after years in prison, the five young men — Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, Antron McCray, Korey Wise, and Kevin Richardson, ranging from 14 to 16 at the time of their conviction — were finally exonerated.

New York City in the late 1980s was, in many ways, unrecognizable from how it is today. Before Rudolph Giuliani took over as mayor in 1994 and instituted sweeping reforms against crime and effectively sanitized the city’s grubby facade and its seedy underbelly of crime, it was a city pressurized by the weight of the crack epidemic, gang violence, and a racial divide that often violently bubbled to the surface.

When a white female jogger named Trisha Meili was brutally assaulted and raped in the city’s scenic Central Park in the heart of Manhattan, The New York Times called it “one of the most widely publicized crimes of the 1980s.”

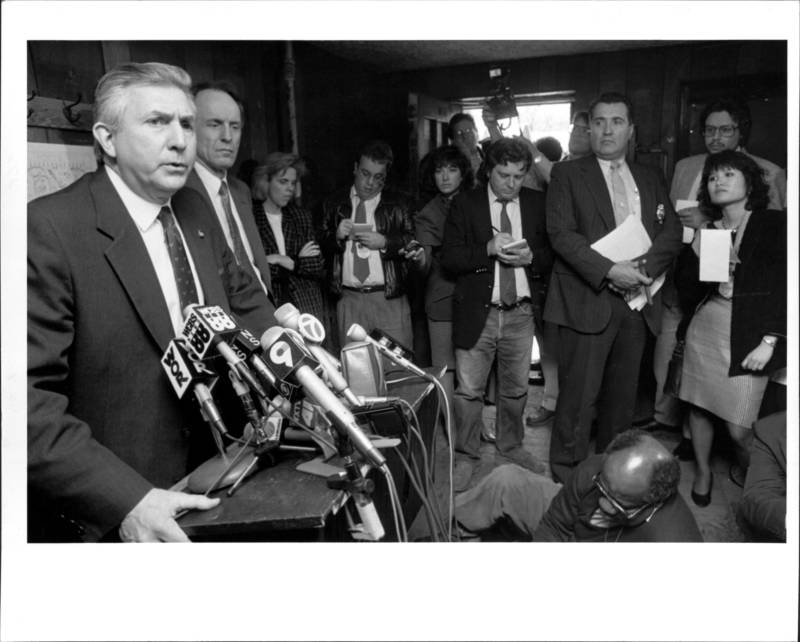

Michael Schwartz/New York Post Archives /(c) NYP Holdings, Inc./Getty ImagesChief of Detectives, Robert Colangelo, describing the attack on Trisha Meili in Central Park. April 20, 1989.

The brutal attack on April 19, 1989 left Meili, a 28-year-old investment banker soon to be known as the “Central Park Jogger,” in a coma for 12 days. She was found in the middle of the night — covered in blood, half-naked, and left in a ravine.

Law enforcement quickly apprehended five juveniles — four of them black and one Hispanic — and tried them for assault, robbery, rape, riot, sexual abuse, and attempted murder. The confessions of the Central Park Five were the only semblance of evidence police had at their disposal to lock the teenagers up — confessions the group later said were coerced.

All five of them received sentences ranging from five to 15 years, much of which they served, even after the truth had been revealed to lawmakers and the public alike.

The Case Of The Central Park Jogger

What really occurred that April night in Central Park involved an anarchistic gathering of criminal mischief and chaos by about 30 teenagers. The trouble-making teens threw rocks at passing cars but the antics quickly escalated to physical attacks on joggers.

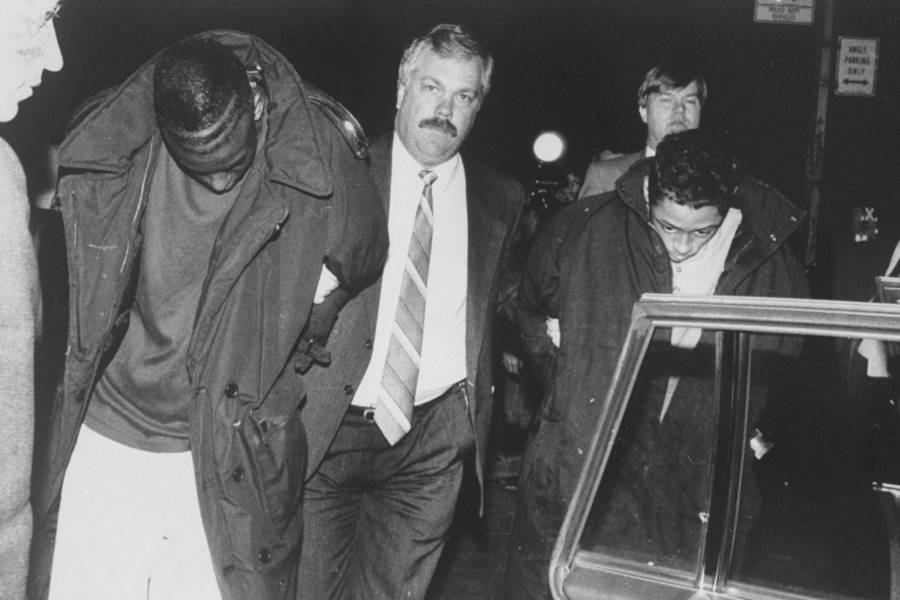

William LaForce Jr./NY Daily News Archive via Getty ImagesYusef Salaam, left, led away by a detective after being arrested in Central Park. April 22, 1989.

The blatant crimes quickly elicited attention and resulted in the arrests of 14-year-olds Kevin Richardson and Raymond Santana, who the authorities suspected were a part of that crew of roving teens for “unlawful assembly.” It was during this time between 9 and 10 p.m. while the two boys were detained in a police precinct, that Meili was assaulted and raped.

When Meili was discovered in a muddy Central Park ravine at 1:30 a.m., Richardson and Santana were still at the Central Park precinct. Meili’s skull was fractured, her body temperature was at 84 degrees, and she had lost 75 percent of her blood. She was nearly dead.

While police at the precinct prepared to let the two boys go — with a mere ticket to attend family court — a detective looking into Meili’s case asked them to keep them there as suspects. It was at this juncture that Meili’s horrific rape and assault was fused with Richardson and Santana’s pubescent mischief.

Interrogating The Central Park Five

The following morning saw countless New Yorkers in a frenzy. The first news reports about the night’s events had flooded newspaper stands, public radio airwaves, and local TV news reports. While Richardson and Santana were being questioned and arguably forced into admitting to crimes they didn’t even know about — police hit the streets to collect more potential suspects. It was during this second round of investigation that 15-year-olds Antron McCray and Yusef Salaam, together with 16-year-old Korey Wise, joined the list, and completed the infamous Central Park five.

Jerry Engel/New York Post Archives /NYP Holdings, Inc./Getty ImagesYusef Salaam leaving court with bodyguards and media in tow. Aug. 1, 1990.

Santana later explained in Ken Burns’ vivid, thoroughly detailed The Central Park Five documentary that he had absolutely no idea of what happened to Trisha Meili but that police had threatened him with the highly likely possibility of spending the rest of his life in Rikers Island if he didn’t confess.

After a minimum of 14, and up to 30 hours of intense interrogation, police offered the Central Park five a seemingly appealing bargain: identify the other members of the group who caused problems in the park that night as the criminals who committed the sexual assault of Trisha Meili, and they could go home.

But since the five boys didn’t know any of the individuals who had attacked joggers in the park that night, they couldn’t conceivably name anyone to blame in the first place — particularly Richardson and Santana, who were in the custody of the law while Meili was attacked.

Four of the five boys were videotaped after days of interrogation matter-of-factly describing the beating of Trisha Meili. Those under 16 had adult guardians at their sides. Richardson, Santana, McCray, Yusef Salaam, and Wise were charged with attempted murder, rape in the first degree, sodomy in the first degree, sexual abuse in the first degree, two counts of assault in the first degree, and riot in the first degree.

Every single one of the five boys retracted their confessions as soon as their interrogations had ended, but charges were already stacked against them.

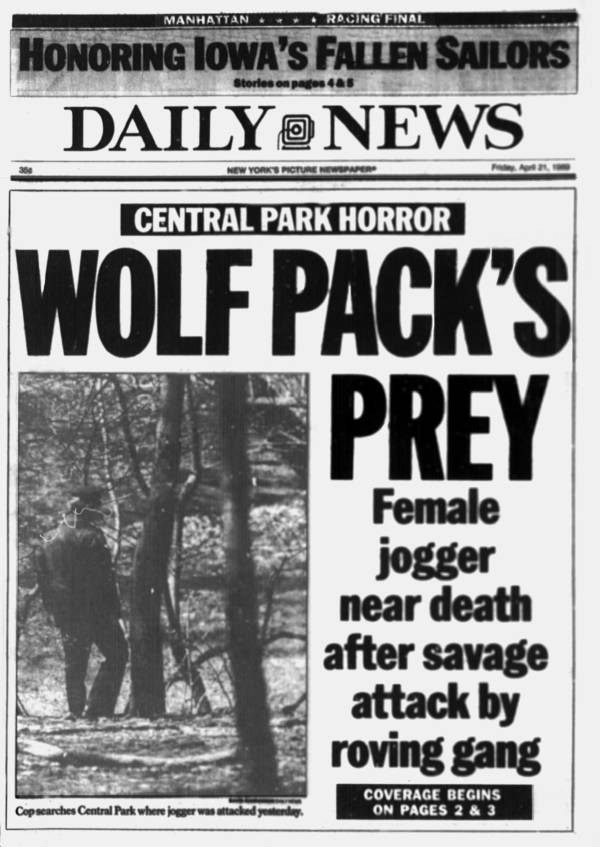

NY Daily News/Getty ImagesThe front page of the New York Daily News on April 21, 1989.

The Media, Donald Trump, And Thinly-Veiled Racism

While Trisha Meili was in a 12-day coma suffering from extreme injuries — a disfigured face, 75 percent of the blood in her body drained, severe cognitive impairment and amnesia upon waking up — the media and prominent New York figureheads supported the case that the five boys were responsible.

None of this was consciously registered by the victim, “Twelve days after the attack, doctors declared that I was no longer in a coma,” said Meili. “But for the next five weeks, I was in and out of delirium and don’t remember anything. So for a told of seven weeks, I just don’t have any memory.”

Shawn Ehlers/Getty ImagesCentral Park jogger Trisha Meili, fully rehabilitated and participating in the Achilles Track Club’s Third Annual “Hope and Possibility” 5-Mile Run/Walk in New York City, June, 2005.

Meili was so badly beaten that the first officer on the scene in Central Park that night gave testimony straight out of a true crime novel. “She was beaten as badly as anybody I’ve ever seen beaten,” the officer said. “She looked like she was tortured.”

Not even Meili’s friends could identify her without the unique ring she was wearing.

Meanwhile, New York was in a frenzy — the city’s rising crime rates had been opportunistically wrangled by conservative politicians and right-wing media outlets to call for harsher laws and increased police spending. The “inherent criminality” of black citizens was clearly a problem they argued, and the Central Park Five case served to prove this.

None other than President Donald Trump, then merely a billionaire playboy and Manhattan real estate legend, shouted this insensitive, racist propaganda from the proverbial rooftops of his Plaza.

“You better believe that I hate the people that took this girl and raped her brutally. You better believe it,” he said at a press conference, and he paid $85,000 for a now infamous full-page ad in The Daily News and other local newspapers to reinstate the death penalty in the case of the Central Park jogger.

I really want this Central Park Five series that's coming to def show the racist ignorance displayed by Trump with his newspaper ads f/ 1989 pic.twitter.com/ALNvRG0Qjo

— Ave (@SebastianAvenue) July 6, 2017

In 2016, Yusef Salaam told Mother Jones that he believed Trump was the actual “fire starter” behind the intense media blitz against him and his friends. Their families consequently suffered under countless death threats and public antagonizing.

The Trials — And The Real Criminal’s Confession

The Central Park Five had their time in court through two different trials, the first of which began in August 1990. Salaam, McCray, and Santana were the first defendants. All five would plead not guilty in the rape and beating of the Central Park jogger, Trisha Meili. Their videotaped confessions, they argued, were entirely coerced. Indeed, none of the seven other witnesses who testified in court about the other incidents of mayhem caused by the crowd of insolent boys could even identify McCray, Richardson, Salaam, Santana, or Wise.

Nonetheless, the jury could not understand why tall five boys would have given confessions to the rape of the Central Park jogger, Trisha Meili, if they hadn’t, in fact, done it.

Though the three boys — still teenagers under 18 — were successfully acquitted of attempted murder, they were ultimately convicted of rape, assault, robbery, and riot charges, and sentenced to five to 10 years in a youth correctional facility.

Richardson was convicted of attempted murder, rape, assault, and robbery during the second trial in December and sentenced to five to 10 years, as well. Wise was convicted of sexual abuse, assault, and riot, and sentenced to five to 15 years. The Central Park Five would come to serve five to 12 years — 12 years for Wise.

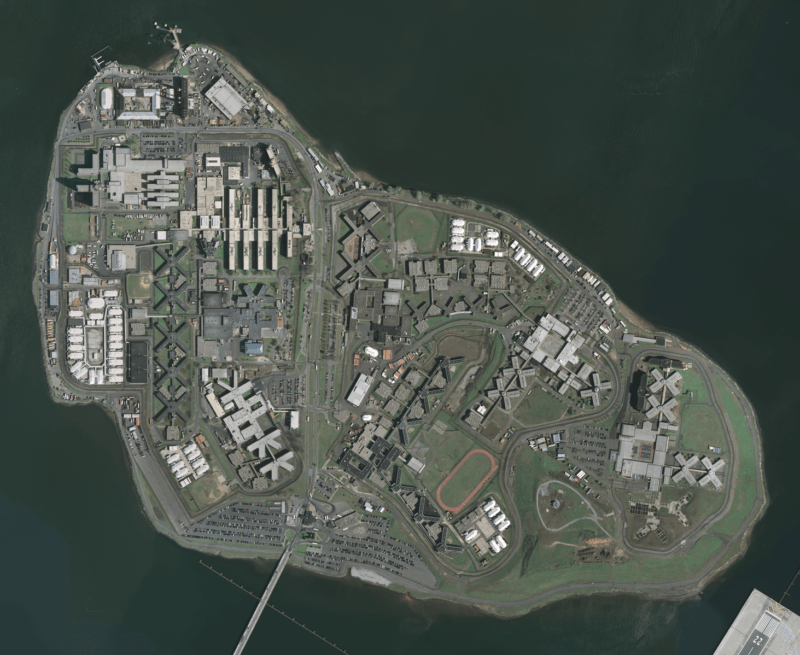

Wikimedia CommonsAn aerial view of Rikers Island in the East River of New York City.

“You’re going to pay for this. Jesus is going to get you. You made this up!”

Wise was charged as an adult and sent to Rikers Island. It was there in New York’s dilapidated prison island on the East River that he met Matias Reyes — a convicted killer and serial rapist serving a 33-year-to-life sentence, who confessed to actually having raped the Central Park jogger, Trisha Meili.

Reyes even admitted to this to prison officials which subsequently led to a DNA test that confirmed his claims.

Graham Morrison/Getty ImagesWoody Henderson (right) from the National Action Network, leading a protest outside of Manhattan’s Criminal Court. Sept. 30, 2002.

New York County district attorney Robert M. Morgenthau officially vacated the Central Park Five’s convictions — a legal move that essentially erases any notion that they were ever found guilty of the crimes that sent them to prison — but the Central Park Five had already served long sentences and grown into adulthood behind bars.

McCray, Santana, and Richardson sued the city for $250 million for malicious prosecution in the Central Park Jogger case, emotional distress, and racial discrimination. The two parties ultimately settled for $41 million, which some people were notably unhappy about.

How much money are the lawyers for the Central Park Five getting out of the 40 million dollars, or are they paid by the City (or both)?

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 22, 2014

Santana was adamant that the lawsuit wasn’t about financial gain — that it was about clearing his name and bookending this decades-long chapter of his life with a clear exclamation mark that firmly cemented him as an innocent victim of the law.

“It was always about closure,” he told The New York Daily News. “So everyone can know without a shadow of a doubt that we’re innocent.”

The Legacy Of The Central Park Five

The story of the Central Park Five became a lightning rod for opportunistic politicians, a bloodthirsty media, and inevitably formed into a rallying cry for a fairer justice system and more oversight for law enforcement. At the time, however, it seemed like an entire city collectively hounded five minority teenagers merely because the NYPD told them they were rapists.

Wikimedia CommonsYusef Salaam, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, David McMahon, Ken Burns and Stephanie Jenkins with the Peabody Award for The Central Park Five documentary. May 2014.

In the end, the five grown men can look back not at a squandered youth behind bars, but at a unified movement standing behind them in support — with Oscar-nominated filmmakers like Ana DuVernay producing a Netflix project on their story, and Ken Burns leaving no single stone unturned in combing through the finest minutia of their trial to provide the public with a factual recounting of events.

As for the Central Park jogger, Trisha Meili, she has since written a book about her experience and gone back to running. She’s also become a celebrated public speaker helping victims of sexual assault to overcome their trauma and grow.

The Central Park Five — regardless of the President of the United States maintaining their guilt as late as October 2016 — have survived long enough to see themselves as icons of resilience, and the perseverance of justice, in a country that too often prevents that from happening entirely.

After learning the truth about the Central Park Five and the attack on the Central Park jogger Trisha Meili, learn about the racist history of New York’s infamous Cotton Club. Then, read about Seneca Village and how white New Yorkers demolished it to build Central Park.