Clandestine, slippery, and young — John Surratt was the only co-conspirator who evaded justice after the assassination of President Lincoln.

John Wilkes Booth, the infamous assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, didn’t act alone. In fact, he was involved with a group of conspirators who would almost all see justice after the death of Lincoln. That is, almost all except John Surratt.

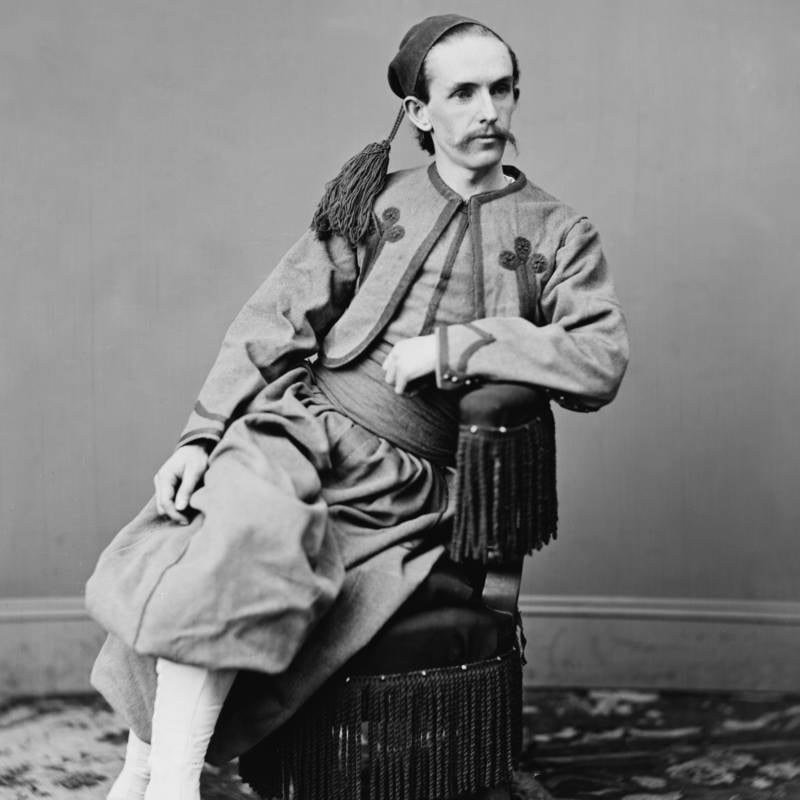

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Surratt in 1867 following his capture in Egypt.

Surratt would manage to escape prosecution for the assassination of Lincoln several times while even his mother was hanged for the crime — he once even launched himself out a prison window and into a pile of human feces to avoid justice.

John Surratt would even be able to live to a ripe old age to tell and retell the tales of his time as a Confederate spy, his part in the plot to kidnap the president, and how he was a co-conspirator in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

John Surratt’s Early Years

John Surratt was born John Harrison Surratt, Jr., on April 13, 1844. His parents lived in Surrattsville, what’s now Clinton, Maryland. The Surratts were fiercely loyal Confederates and owned around six slaves. Their town was south and east of Washington, and farmers there traditionally kept slaves to work their fields.

Farming proved not to be the Surratt-family forte, and after their tobacco crop failed, Surratt’s father built a tavern in town. The family also owned a blacksmith shop and carriage shop, and their patriarch became the postmaster of Surrattsville.

John Surratt Jr. enrolled in St. Charles College in 1859 at the age of 15. He intended to enter the priesthood as his mother, Mary Surratt, was a devout Catholic. His father, however, had accumulated large amounts of debts both from his failed farm and from his tavern, and as he drank himself away, talk of secession and rebellion flared across the country.

As slave owners, the Surratt’s didn’t want to see their cushy way of life disappear. They ardently joined the war effort for the South.

In July 1861, the younger Surratt left school and returned home. By this point, several states had seceded from the Union and the Battle of Fort Sumter had already started the American Civil War.

The Surratt boys, John Jr. and his brother Isaac, were quick to join the Confederate cause. Isaac became a member of the Confederate Army in Texas in the 33rd Cavalry. John, still under 18, signed up with the Confederate secret service. Anna, their sister, ran the tavern in Surrattsville which became a meeting place for Confederate forces.

Upon John Sr.’s death in 1862, his namesake John Surratt Jr. succeeded the father as postmaster. Between the tavern and the post office, it was easy to hide messages to and from spies within the Confederacy.

There was an entire network of postmasters in southern Maryland, technically a border state, that sent messages from Richmond to operatives in the north — and it was all under the eye and fist of the Surratt family.

His Confederacy Espionage And Conspiracy

John Surratt carried out his duties well, and sometimes for a price. Hand-delivering clandestine messages needed extra time, effort, and cash. His most common duty was relaying dispatches regarding troop movements in and around the nation’s capital and delivering them to Confederate boats stationed on the Potomac River.

Wikimedia Commons John Surratt in 1868.

After the war, Surratt remarked how he carried these secret messages “sometimes in the heel of my boots, sometimes between the planks of the buggy.” He mocked the Union officers he escaped, “I confess that never in my life did I come across a more stupid set of detectives than those generally employed by the U.S. government.”

He was once arrested in 1863 but released without much trouble. Indeed, Surratt came to be exhilarated by and enjoyed his clandestine missions outsmarting his enemy.

Then in the fall of 1864, Surratt met his destiny. A mutual friend, Dr. Samuel Mudd, introduced Surratt to the handsome and wealthy John Wilkes Booth.

Booth then introduced Surratt to the idea that bold actions could help the South to win the war. He told Surratt of a grand plan to kidnap Abraham Lincoln, transport him to Richmond, and then barter for his life. Booth wanted the federal government at the very least to release thousands of Confederate prisoners of war. At most, Booth hoped he could negotiate better terms for the South.

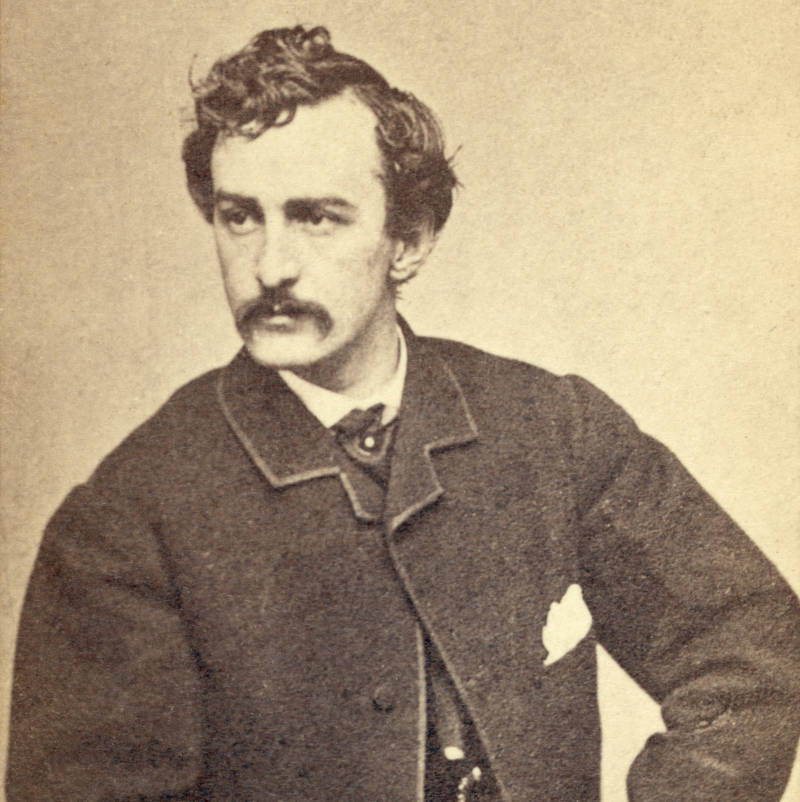

John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin.

Surratt was initially opposed to the idea of kidnapping Abraham Lincoln — he thought it was foolish. But Booth outlined so precisely what would happen, the when, the who, and the how, that Surratt eventually assented.

The Failed Kidnapping Of Abraham Lincoln

By 1865, Mary Surratt, the matriarch, leased her tavern to a neighbor and opened a boarding house mere blocks from Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. where Confederate agents met and conspired. The Confederates met regularly there, until the afternoon of March 17, 1865, when Surratt and Booth heard that Lincoln was planning to attend a play.

It was a production of Still Waters Run Deep at Campbell Hospital. The location was near the old soldier’s home on Seventh Street Road at the outskirts of Washington. Unlike a place like Ford’s Theatre, security here was not much of a concern. The kidnapping had to happen quickly. Surratt and Booth, in conjunction with six others, gathered their supplies, mounted their horses, and galloped to the scene.

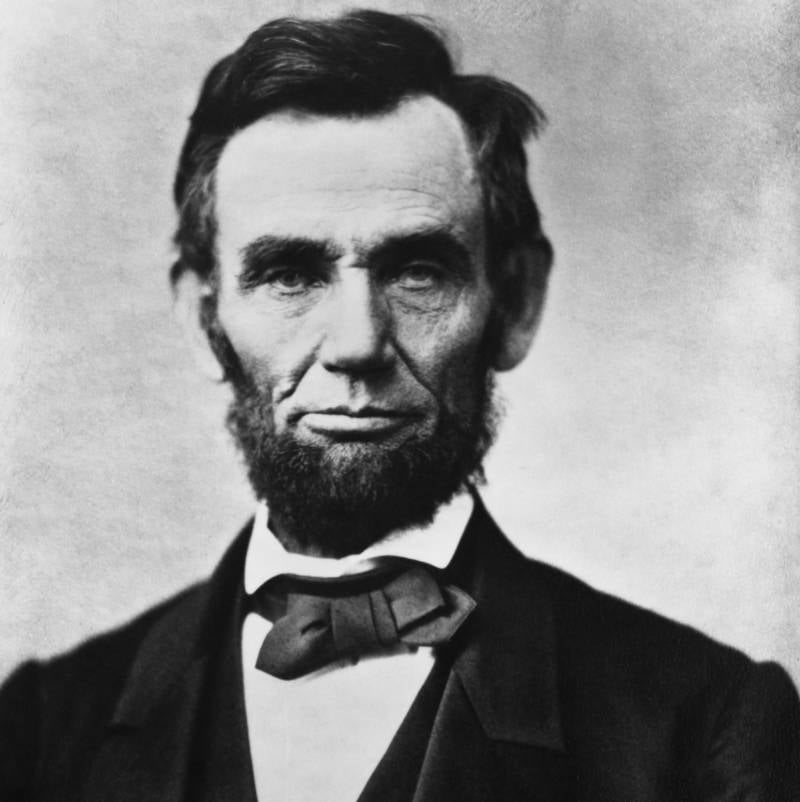

Wikimedia Commons Abraham Lincoln during his presidency.

In their pack were guns, swords, knives, a rope, and a monkey wrench. The guns and swords were an obvious choice. They needed firepower to defend themselves. Booth and Surratt headed to the play.

If all went well, they would commandeer the president’s carriage. Surratt would drive the carriage surrounded by armed men, and once the horses reached the Potomac River in southern Maryland, the men would use the monkey wrench to remove the wheels on the carriage. This would make crossing the Potomac easier. They could then switch carriages completely once they reached the other side and landed in Virginia.

But the daring plan was for naught. Lincoln didn’t even show up for the play that day. Either their intelligence had failed, or the Union had figured out their plan. The next time the conspirators met in April, Booth insisted murder was the next best option. The rest of the group, allegedly, said that assassination was not a part of the discussion.

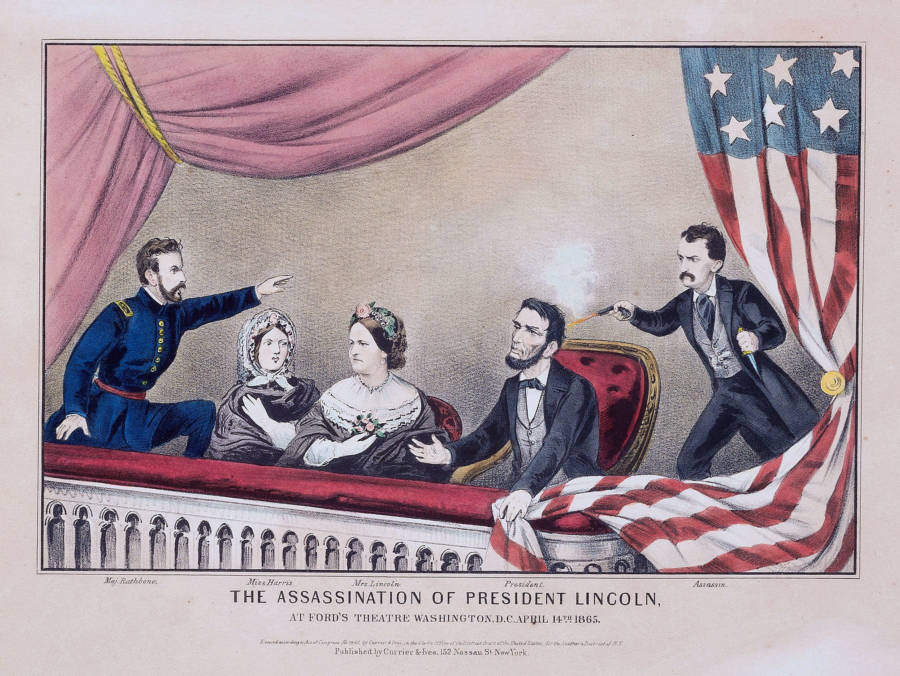

Four weeks after the botched kidnapping, Booth assassinated Lincoln in Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865 as he watched a play with his wife Mary. John Wilkes Booth died a few weeks after the assassination when Federal troops surrounded a barn where he was hiding and Union soldier named Boston Corbett shot and killed Booth.

Wikimedia Commons A depiction of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Federal officials arrested Surratt’s mother on conspiracy charges three days later. After all, it was her boarding house where the group of men had met to plot the kidnapping and assassination of President Lincoln. Other men in the group of conspirators named John Surratt as an accomplice, as well.

But John Surratt was nowhere to be found.

The Great Escape Of John Surratt

John Surratt fled to Richmond shortly after the failed kidnapping plot and he claimed later that the Confederacy ordered him to take dispatches to Canada. Official accounts differ from this, but either way, Surratt maintained that he was nowhere near the assassination when it transpired.

After Lincoln’s assassination, Surratt stayed in hiding.

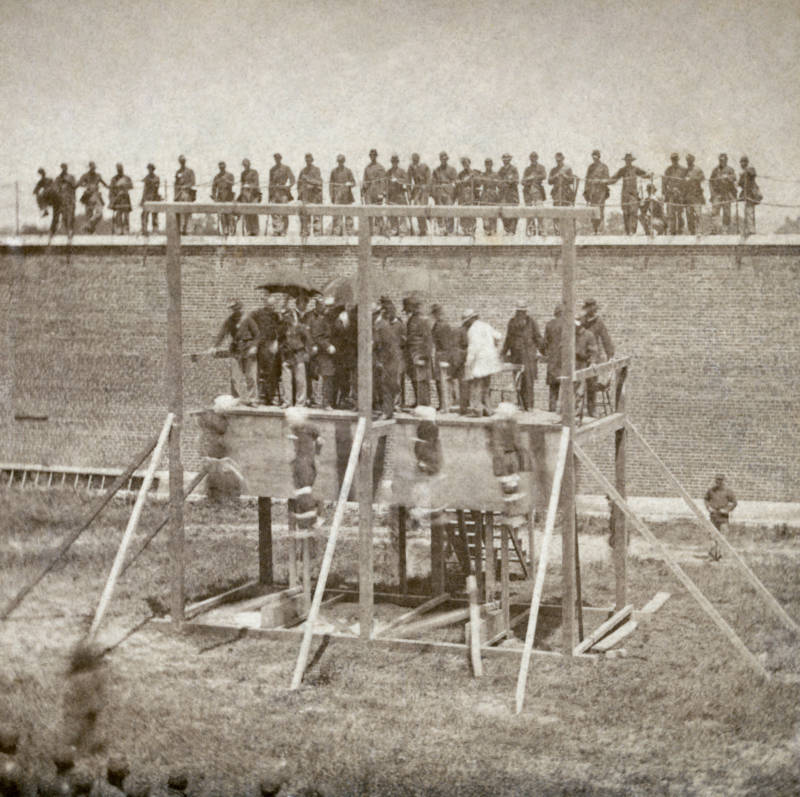

He was in New York when he heard the news of Lincoln’s death and then he allegedly fled to Montreal rather than face prison. Surratt’s co-conspirators vilified him for going on the run. His own mother was hanged alongside three cohorts — Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold — and just three months after Lincoln’s assassination on July 7, 1865. They faced a military tribunal rather than a civilian court as the assassination was considered an act of war.

Upon his mother’s death, John Surratt said, “I had nothing now to bind me to this country. For myself, it mattered little where I went, so that I could roam once more a free man.” Mary Surratt was the first woman to be executed by the U.S. government.

Wikimedia Commons The execution of the Lincoln Conspirators by hanging, July 7, 1865. Mary Surratt is on the far left.

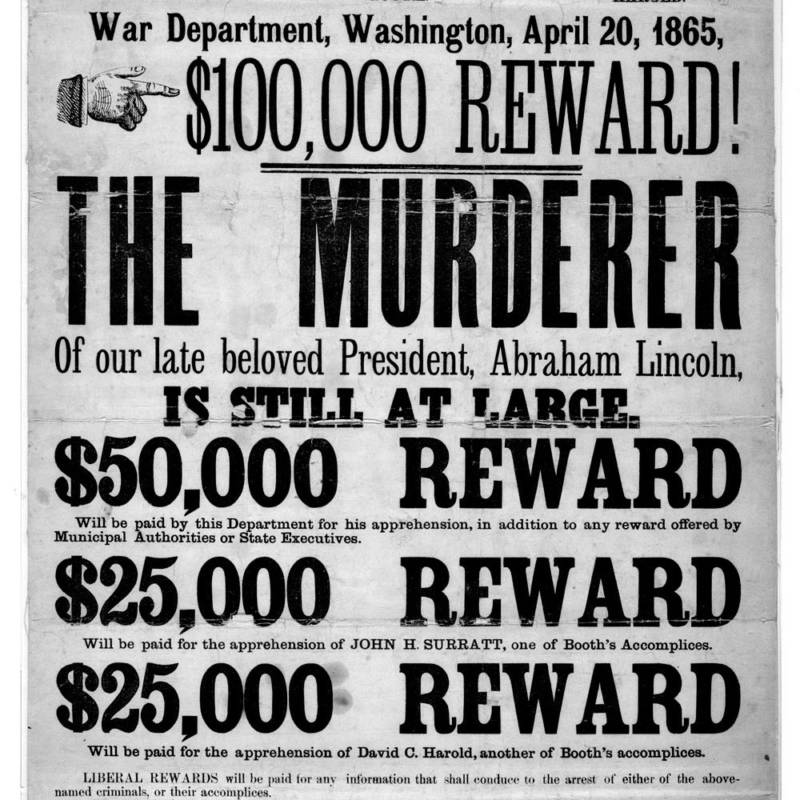

Federal officials put out a bounty of $25,000 for information leading to Surratt’s arrest, the modern equivalent of $300,000. That bounty would be the bane of Surratt’s existence for a while, so he fled to Canada in September 1865. He dyed his hair dark brown, donned spectacles, and played the part of an Irishman headed home. Eight days later he was in Liverpool.

He made his way to Italy to serve in the Papal Zouaves or the Pope’s military. These were an army of Catholics who waged war in the name of the Pope. The idea was to prevent Italy from taking possession of the Papal States, thereby reducing the power of the Pope in his home country.

But even in disguise and miles from the States, Surratt wasn’t safe. Henri Beaumont de Sainte Marie, an acquaintance of John Surratt’s from Maryland, had tracked him down. He also joined the Papal Zouaves, if only to collect the bounty on Surratt’s head. In April 1866, Beaumont contacted the U.S. government.

Wikimedia Commons A wanted poster from 1865 showing the bounty for John Surratt.

He wasn’t an easy catch, though. As a former postmaster, Surratt intercepted the letter of his impending arrest and fled immediately. Papal authorities pursued him to a mountaintop in Veroli and threw him in jail a day later. But his captors made the mistake of allowing him to go to the bathroom.

Surratt launched himself out of the window and landed in a pile of human feces. The soldiers who saw him do it were in shock. One said, “It seemed quite impossible to us to clear. This perilous leap…might have broken his bones a thousand times, and gain[ed] the depths of the valley.”

Surratt made it to a boat bound for Egypt. Because of a cholera outbreak, officials quarantined passengers of the boat in Malta and it was there that American officials finally caught him.

The Trial Of The Century

By now, John Surratt’s exploits had become dime-novel material. Everyone in the United States knew who he was. Unlike his mother, Surratt faced a civilian court rather than a military one. There would be no swift justice as in the case of his mother who went to the gallows mere weeks after Lincoln’s assassination.

More than 300 witnesses came forth at his trial. Some testified that he was in New York on April 14, 1865. Others swore that he was in the audience in Ford’s Theatre when Booth opened fire. Prosecutors said he was a key person in the plot to kill Abraham Lincoln. Surratt’s attorneys maintained that he didn’t know about the assassination plot, only the kidnapping plot.

The jury couldn’t decide. Ten months later, a judge threw out a prosecutor’s attempt to try Surratt again because the statute of limitations had lapsed: 23-year-old Surratt was a free man.

He spent the next seven months in South America. He returned to the United States in 1870 to go on a lecturing circuit about his adventures as a Confederate. For 50 cents, people could listen to the young Surratt’s tales of rebellion, escape, and conspiracy. He openly admitted he knew John Wilkes Booth and that he knew of the plot to kidnap Lincoln, but Surratt always maintained that he never heard of a plot to assassinate the president.

Unlike his co-conspirators, Surratt lived to old age and he died on April 21, 1916, less than two weeks shy of his 72 birthday — and very near the anniversary of his friend’s bullet meeting with the president’s head. Surratt would be remembered as “one of the most thrilling incidents of the years following the Civil War.”

After this look at John Surratt, discover the forgotten story of Edwin Booth, the famous actor brother of John Wilkes Booth who’d voted for Lincoln. Or, learn about Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, the last known direct Lincoln descendent.