Since Theresa Kachindamoto's time as senior chief in the Dedza district of Malawi, the country has increased the legal age of marriage consent from 15 to 18.

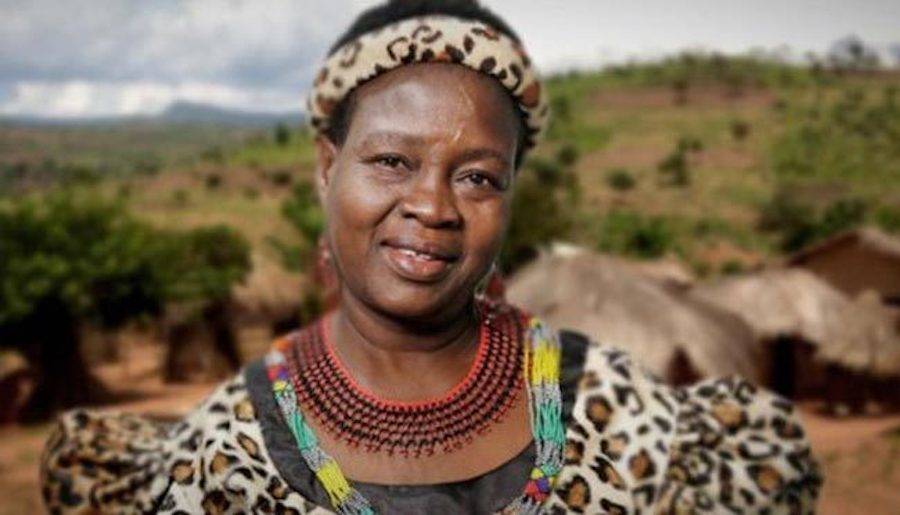

TwitterTheresa Kachindamoto, senior chief in Malawi’s Dedza district.

Theresa Kachindamoto’s time as senior chief of the Dedza district in Malawi was largely spent on a singular issue: child marriages. Though she understood they were culturally accepted and borne out of financial necessity, the practice struck her as one that brought deep, irreparable harm and simply had to be eliminated.

While arranged marriages are an accepted custom in many parts of the globe, the cultural norm has extended to small, underage girls in the southeastern African nation of Malawi. The common practice has seen countless children separated from their families, and forced into marriages with men they’d never even met, according to Healthy Food House.

Malawi was recently indexed by USA Today as the sixth poorest country in the world — a likely factor in attempting to secure a child’s future and safety through the prospect of arranged marriage.

Theresa Kachindamoto’s First Order As Chief

For Theresa Kachindamoto, who spent 27 years as a secretary at a city college in the Malawi district of Zomba, that troubling safety net of child marriages had become entirely unacceptable, wrote Al Jazeera. As the descendant of chiefs, the youngest of 12, and the mother of five — she soon found herself in a position to challenge the practice.

When her lineage suddenly thrust her into the status of a senior chief to more than 900,000 people, Kachindamoto got to work — and annulled 850 child marriages before sending those girls back to school.

Charlie ShoemakerTheresa Kachindamoto with her village elders.

When the chiefs asked Kachindamoto to return to Monkey Bay, mountainous terrain around Lake Malawi in the Dedza district, they made sure to compliment her before shouldering her with certain responsibility.

Kachindamoto recalled that her elders chose her as the next senior chief because she was “good with people” and told her that she now owed her tribe dutiful leadership “whether I liked it or not.”

After she made the rounds to meet those under her cultural jurisdiction, touring the homes constructed out of mud walls and grass-covered roofs, Theresa Kachindamoto was stunned to find countless young girls greeting her as the wives of their adult husbands.

“Whether you like it or not, I want these marriages to be terminated,” she said.

It was her very first day as senior chief.

Underage Sexual Initiation

In 2012, it was revealed that half of the girls under 18 in Malawi’s underdeveloped areas were forced into marriages with adults. Though a law passed in 2015 forbidding this practice, it did little to curb the problem — parents still engaged in the arrangements, often for financial reasons.

“I see girls being abused, sent to be prostitutes, taken out of school as parents have no money,” explained Mary Waya, a former child abuse victim who grew up to become the coach for Malawi’s national netball team.

Perhaps most troubling were the sexual initiation camps girls were sent to upon having their first periods, where they were encouraged to learn what pleases a man and practice sex to understand their “duties.”

This stage of sexual preparation is called “kukasa fumbi,” or cleansing. Some of these girls can only graduate by having sex with the teacher there or otherwise return home virgins — only for their parents to get “hyenas,” local men, to take their virginities.

Kukasa fumbi has tragically furthered the regional spread of HIV — in a country where one in 10 is infected with the virus — and led to numerous unwanted pregnancies. Condoms are rarely used.

Waya said that “in the village, you find some of these chiefs agree to do this cleansing.”

Wikimedia CommonsTheresa Kachindamoto receiving the 16th annual Navarra International Solidarity Award in 2018.

Political Pressure And Local Backlash

While Malawi has a functioning democratic government with its own legal structures and authority figures, chiefdom has been its own culturally valued and respected leadership position for hundreds of years.

Together with 50 of Theresa Kachindamoto’s sub-chiefs, she formed and signed an agreement to end child marriages in the district. This immediately put an end to minors being able to marry and terminated the sexual initiation camps.

“I said to the chiefs that this must stop, or I will dismiss them,” said Kachindamoto.

There were four male chiefs who opposed Kachindamoto’s agreement — whom she fired on the spot.

This fundamental restructuring of regional norms was met with extreme aggravation by many. Outside of Kachindamoto’s jurisdiction, chiefs and police “can’t intervene” at all because the backlash is so vigorous.

“Most of them say ‘It’s better that she gets married. We can’t afford to keep her…she will make us poorer,’” said Emilida Misomali, in reference to the economic motivation of parents — which Theresa Kachindamoto’s efforts have threatened.

But the senior chief’s morals and ambition to help the innocent have allowed her never to waver. She stood firm and let the old guard understand how serious she was.

“I don’t care, I don’t mind,” she said. “I’ve said, whatever, we can talk, but these girls will go back to school.”

Wikimedia CommonsThree Malawi children.

The four fired chiefs eventually made sure that those in their former districts adhered to the new law. Kachindamoto hired them back once she verified this and then began to draw up plans to implement her new agreement into civil law. This required community members, committees, charities, and the clergy.

“First of all it was difficult, but now people are understanding,” she said, adding that she’d received countless death threats.

The determined chief developed a network of “secret mothers and secret fathers” throughout the villages in order to continuously ensure that nobody is covertly taking their kids out of school for veiled marriages.

“I tried to call some girls from town so that they could be role models, so that they could come to schools to talk,” said Kachindamoto. “If they are educated, they can be and have whatever they want.”

When asked whether she’d ever see herself having an ordinary job like a secretary at a city college again, Theresa Kachindamoto laughed.

“I’m chief until I die.”

After reading about Malawi senior chief Theresa Kachindamoto ending the country’s practice of child marriages, learn about the dark history of Mormonism from mass murder to child brides. Then, take a look at 13 shocking photos of child marriages around the world.