The Cotton Club had a reputation for catapulting famous careers, but history has a way of glossing over the cabaret's social transgressions.

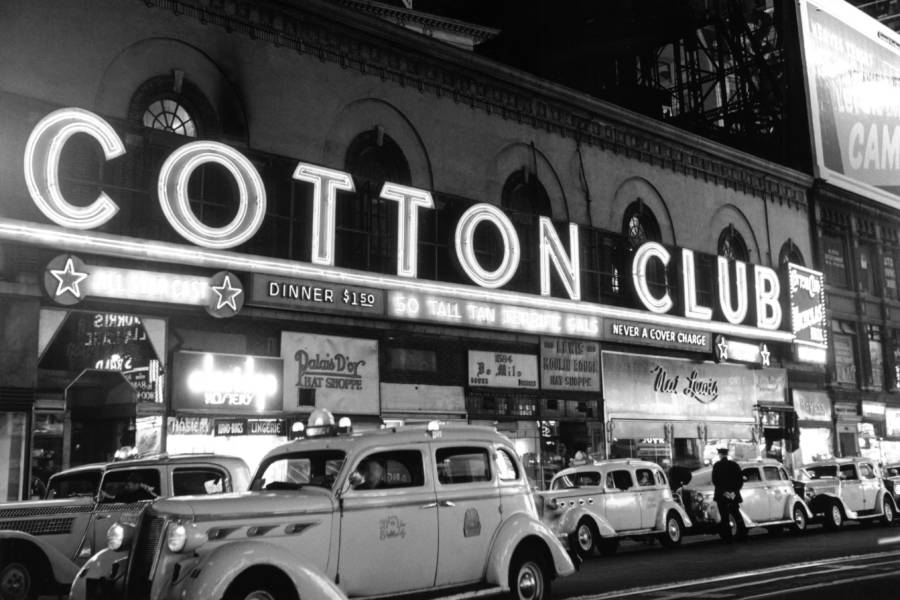

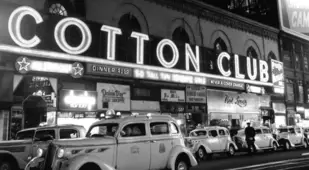

If there was a staple of Harlem nightlife in the 1920s and 30s, it was the Cotton Club.

Boasting some of the era's most talented performers, the entertainment venue and speakeasy remains an icon of New York City even today. But as much as we praise the club for bringing names like Duke Ellington and Lena Horne into the spotlight, the truth was that the Cotton Club functioned under a very thinly-veiled cover of racism — and A-listers gobbled this up faster than prohibition booze.

The Grand Opening

African-American heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson purchased a fledgling casino at 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem in 1920. Under the name Club Deluxe, Johnson's supper club didn't have much success. It wasn't until the gangster Owney Madden acquired the property from the boxer in 1923 and renamed it the Cotton Club that things took off.

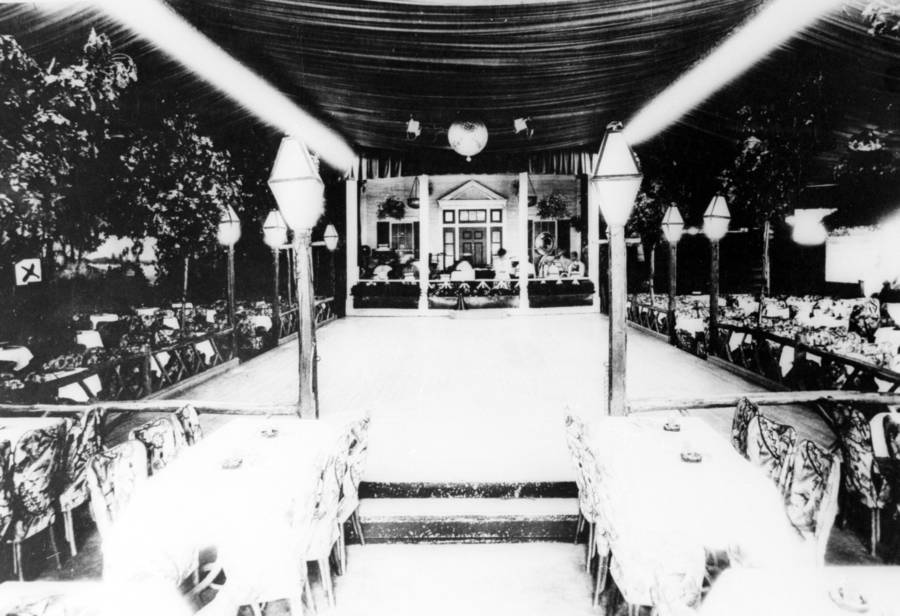

Madden spent lots of cash renovating his new business venture, which he used as a vehicle to sell his "No. 1" beer during the American Prohibition-era. He kept Johnson on as manager and redecorated the club in a mix of Southern plantation and jungle-type decor. Not only did he make the stylistic choice of reinforcing the racial stereotypes of the time through this redesign, but Madden also made the club into a whites-only establishment.

In fact, the Cotton Club had the strictest segregation policy of all the Harlem cabaret clubs at the time. Ultimately, attending this cabaret was a way for white people to indulge in two taboos simultaneously — to drink and mingle with black people.

Cotton Club Acts

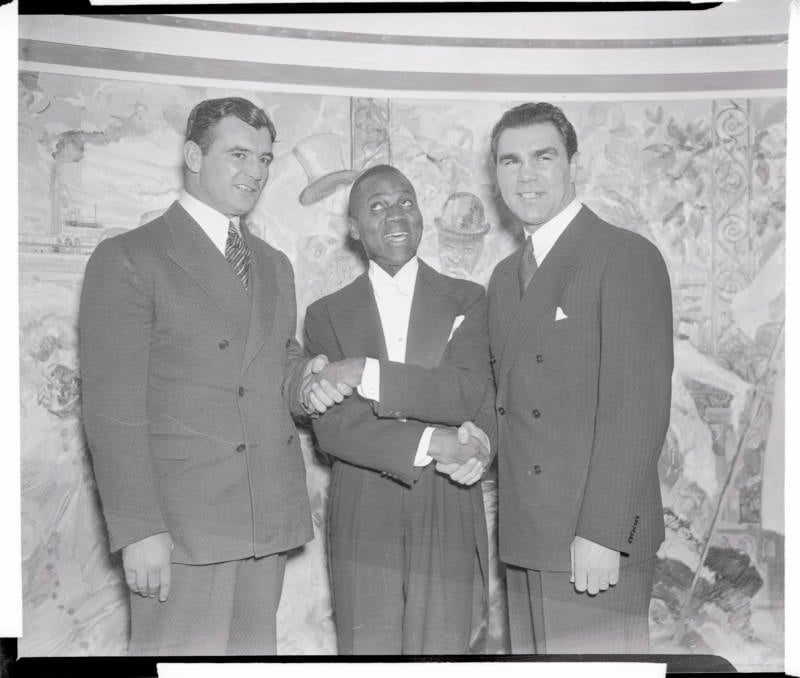

Many genuine talents got their start at the infamously bigoted but popular speakeasy.

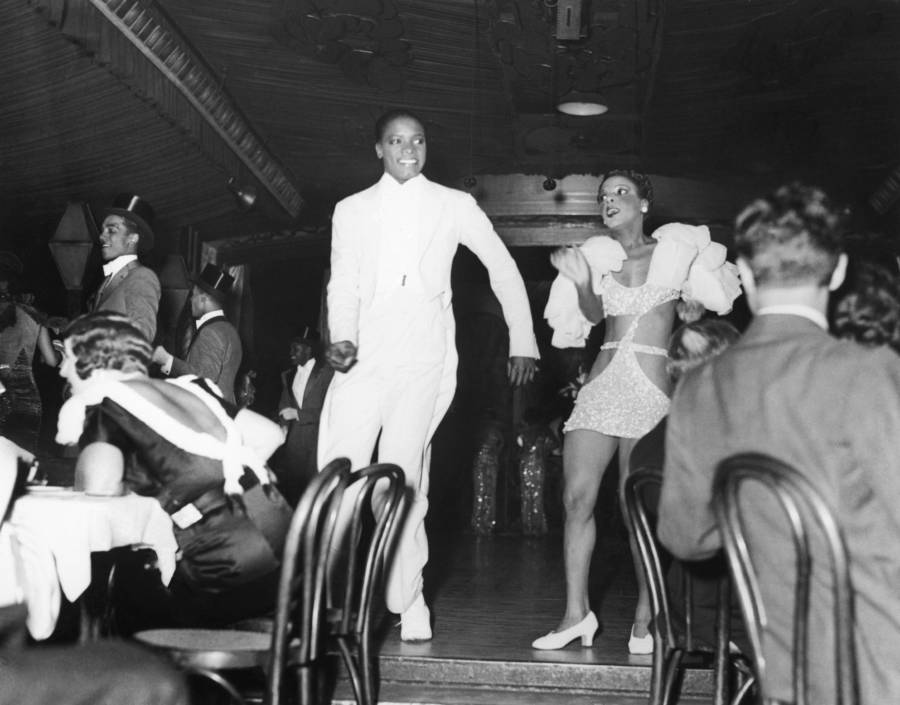

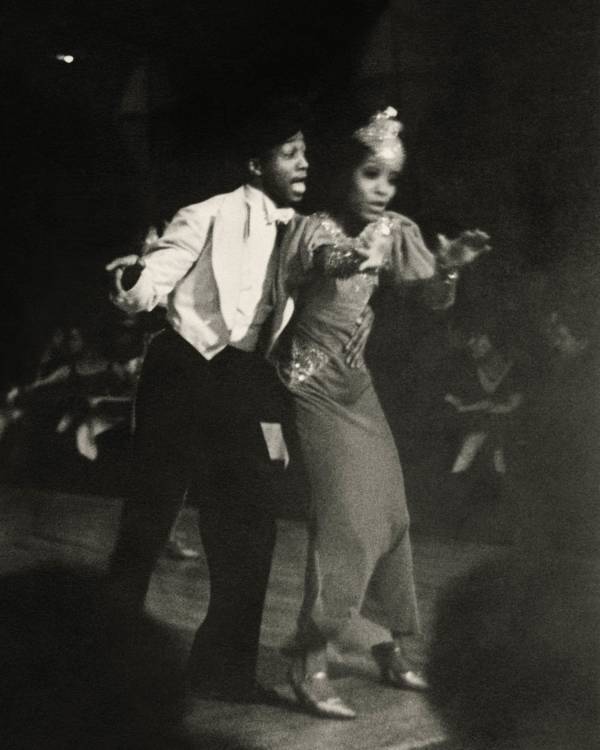

The overall entertainment consisted of musical revues, singing, dancing, comedy, variety acts, as well as the famed house band. Fletcher Henderson was the first bandleader, with Duke Ellington famously taking the helm in 1927. Ellington recorded over 100 compositions during this time — and his musical talents ascended him to the top of the Jazz Age.

The Duke also had a hand in the Cotton Club later relaxing its segregation policy — even if only slightly.

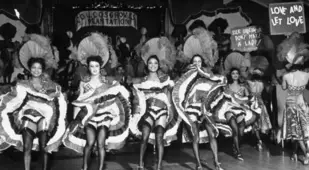

Other awe-inspiring acts included Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, Adelaide Hall, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Ethel Waters, and Louis Armstrong. In 1934, Adelaide Hall starred in the "Cotton Club Parade," the highest-grossing show the club ever had. It ran for eight months, brought in 600,000 customers, and marked the first time that dry ice was used onstage as a fog effect. A 16-year-old Lena Horne appeared in the show as well under her real name Leona Laviscount.

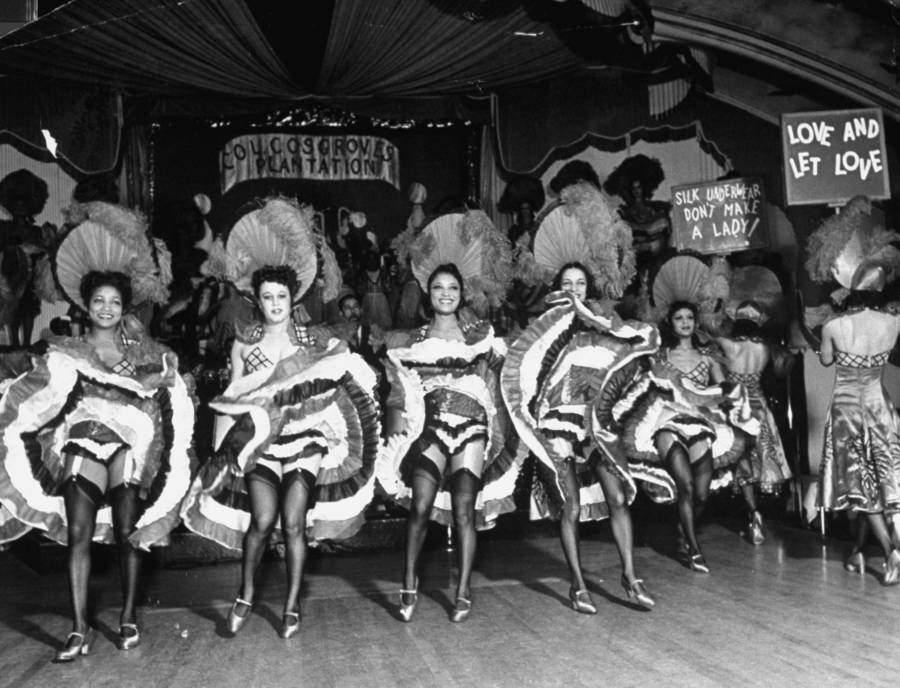

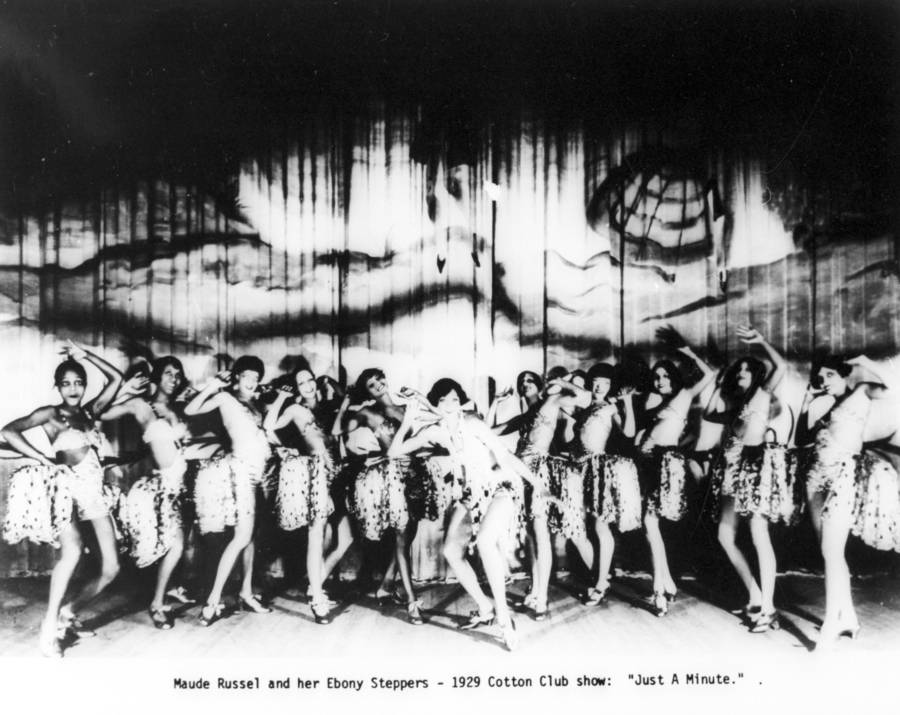

It took a very specific type of girl to become a dancer at the Cotton Club. Hopefuls needed to be 5'6" or taller, light-skinned African-American, and under 21 years old.

The chief form of entertainment was the floor shows. "The chief ingredient was pace, pace, pace," the shows' director Dan Healy observed. "The show was generally built around types: the band, an eccentric dancer, a comedian - whoever we had who was also a star...And we'd have a special singer who gave the customers the expected adult song in Harlem."

"No one was allowed to talk during the shows," remembered Ellington. "I'll never forget, some guy would be juiced, and talking, and the waiter would come round...and then the next thing, the guy would just disappear!"

A Sign Of The Times

Though the owners of the Cotton Club paid their entertainers well, those talents experienced their rise to fame at a venue that promoted the very stereotypes against them.

"The Cotton Club and other segregated nightclubs didn't just slap local residents in the face, but promoted and gave respectability to a vision of African-Americans that the Harlem Renaissance was desperately combating."

Titled On the Shoulder of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance, Abdul-Jabbar lamented that "the Cotton Club, which promoted the inferiority of black identity, was a major obstacle that had to be overcome."

Upon a visit to the Cotton Club, the black writer and poet Langston Hughes, who was only let in because of his well-known status, commented on the vibe inside the cabaret. "Harlem Negroes did not like the Cotton Club ... nor did ordinary Negroes like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers — like amusing animals in a zoo."

Indeed, other Harlem nightclubs like the Savoy Ballroom, Lenox Club, and the Renaissance Ballroom were where black Harlem-ites truly felt welcomed. At the Cotton Club, the black performers did not mix with the white clientele. When the shows were over, author Steve Watson wrote that performers "visited the basement of the superintendent at 646 Lenox, where they imbibed corn whiskey, peach brandy, and marijuana."

The Decline And Legacy

The original Cotton Club was at the height of its popularity from 1922 to 1935. But in the wake of the Harlem riots in 1935, the club relocated to another New York location and never regained its earlier magic. It closed in 1940.

A Chicago branch of the Cotton Club was run by Ralph Capone, Al's brother, and a California branch in Culver City, California during the late 1920s and into the 1930s. There's still a Cotton Club in operation today in New York City, though it seems to be a tourist attraction for their Sunday Jazz brunch more than anything else.

Perhaps most notably, there was a West coast parallel to Harlem's Cotton Club — with a few important differences. San Diego's Hotel Douglas opened its doors in 1924, with its own nightclub called the Creole Palace. This California club, also known as the "Cotton Club of the West," featured prominent figures such as Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, and Count Basie.

The Creole Palace was a business created by — and catered primarily to — the African American population and as such employed light and dark-skinned dancers in a variety shows which offered most of the same fare as the original Cotton Club. One addition was the burlesque shows, which featured mixed-race entertainment at a time when the rest of the nation was still segregated.

Next, dive further into the 1930s with these photos of high-society people with no time for the Great Depression. Then immerse yourself in the Harlem Renaissance with these photos that define a movement.