From hatred of singing and dancing to comparing women to snakes, these Buddhist teachings reveal that this religion isn't exactly the paragon of peace and love that so many ill-informed Westerners think it is.

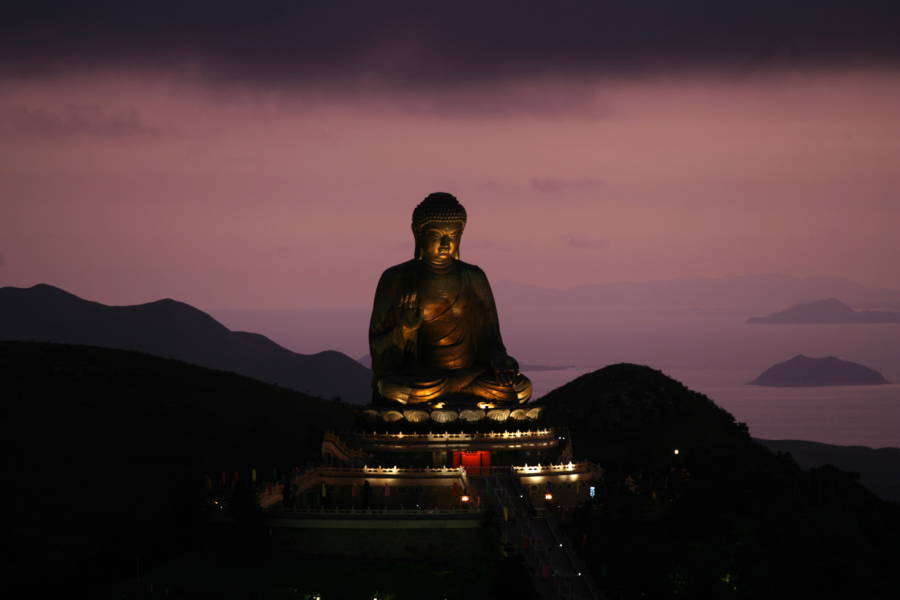

ANTONY DICKSON/AFP/Getty ImagesThe Tian Tan Buddha — at 112 feet tall, the world’s largest outdoor, seated, bronze Buddha statue — looms over Hong Kong.

The Buddha has become a living personality in Western pop culture, though one that is often but a tissue of romantic projections and postmodern Orientalism. The Buddha long ago joined the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Albert Einstein, and the Dalai Lama as the face of a million Internet memes offering up feel-good bits of wisdom he never actually said and, in many cases, would never say.

Even among Buddhists who read the teachings of the historical Buddha, there isn’t much of a sense of the Buddha’s human personality and pre-legendary biography. This is chiefly because the oldest Buddhist scriptures are massive — thousands of pages long, 40 volumes in one popular edition.

In fact, most followers are only familiar with the Buddhist teachings that are regularly chanted in temples or published in collections of the Buddha’s most important teachings. And as for the biography of the Buddha himself, his legend long ago overtook what the earliest sources actually say.

What’s more, the Buddha’s true personality and opinions would shock many Westerners (and even some Buddhists).

I was able to read most — not all — of the Pali Tipitaka (the original and most complete canon of Buddhist scripture, and the source of the quotations and stories below) during the three years I spent living in a Buddhist monastery. And what I found revolutionized my understanding of both Buddhist teachings and who the Buddha was as a human being.

What Was The Buddha Really Like?

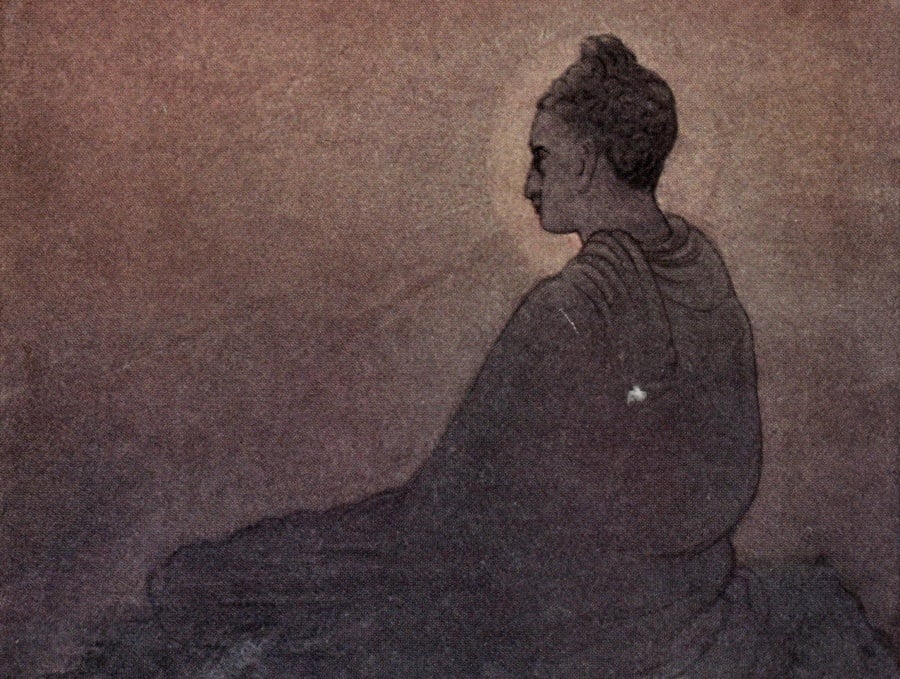

Wikimedia CommonsThe Victory of Buddha by Abanindranath Tagore

Far from his cheerful and cherubic depictions today, the Buddha viewed the world as full of ugliness and suffering — a worldview which started from a relatively early age. According to the Buddha’s portrayal of himself, he grew up in great wealth in present-day India sometime between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE but as a young man left home to become a religious wanderer. He did this against the wishes of his parents, who wept and mourned at their son’s decision.

The Buddha tells us that he left home because he was horrified and humiliated by the universal nature of illness, suffering, and death and wanted to seek a reality that transcended such things. It was this quest that motivated him to wander into the Indian jungle with its growing culture of spiritual philosophers and renunciants.

After attaining what he called nirvana (the ultimate state of enlightenment), the Buddha taught others for 45 years. As a teacher in later life his character was stern, ascetic, and possessed of remarkable integrity and clarity of vision. His spirituality was practical: He claimed he was only concerned with leading people to the transcendence he had achieved and the freedom from suffering it offered.

The Buddha was so keen on the transcendence he’d found because he saw the universe as an ultimately meaningless prison and the truths he’d discovered as the escape route. The Buddha compared human life to torture, debt, prison, being burnt alive, and being afflicted with leprous sores. He view eating food as a violent act, akin to cannibalizing your only child — a comparison which likely won’t show up as a Facebook meme anytime soon.

Yet, despite the Buddha’s despair at the human condition, he was a man of deep compassion and humanity who relieved what suffering he could with what wisdom he thought others could absorb. The Buddha tirelessly taught others and developed communities that would practice his ways, gradually setting down a detailed code of monastic rules and etiquette. He remained a poor wanderer until his death.

Contrary to popular Eastern (and, by extension, Western) images of him as a plump, long-haired demigod with a perfect complexion, the Buddha shaved his head, and in his later years was indistinguishable to visitors of his community from any other members of his gang of ragged, wandering monks.

No Singing, Dancing, Or Jokes, Please

Wikimedia Commons

The Buddha was what you might call a staunch puritan. He advised his lay followers not to frequent public festivities or carouse at night or to gamble, and to be exceedingly frugal. He told his monastic followers to wander alone “like rhinoceros horns,” avoiding the conflict and stress of companionship unless there was spiritual insight to be gained from it.

Furthermore, the Buddha was also a critic of the human body itself, calling it “a sack full of impurities” and a “festering boil.” To cure their lust, he taught his monks to meditate on how revolting it was. The Buddha didn’t stop there: He detailed a series of cemetery meditations in which monks would watch human bodies in various stages of decomposition.

In fact, the most marked failure in the history of Buddhist teachings was surely when a large group of monks whom he had taught to meditate on the loathsomeness of their own bodies committed suicide as a result (the Buddha then modified his instructions so that monks would keep their psychic balance while meditating on the body).

In addition, the Buddha compared singing to howling, dancing to lunacy, and laughing out loud to childishness, advising his followers to give up singing and dancing and be content with only moderate smiling.

In one case, the Buddha had harsh words for an entertainer who believed that after death he would be reborn in a heaven of laughing angels. Far from being rewarded for making people laugh, said the Buddha, the entertainer would in fact be reborn in “the hell of laughter” for filling people’s minds with delusions.

And despite the Western view of Buddhist teachings as empirical, practical, and even scientific, he in fact claimed to speak regularly to devatas (spirit beings from a higher plane than the human) and claimed that he and some of his disciples had supernatural powers: ESP, telekinesis, astral travel, flight, and more.

Misogyny In Buddhist Teachings

OLIVIER MORIN/AFP/Getty ImagesA girl sits by Buddhist monks during a public event with the Dalai Lama in Trento, Italy.

The Buddha’s record with women is complex and contradictory — and not exactly what you may imagine when thinking of tantra. While he affirmed women’s equal potential in the spiritual life by proclaiming that they too could attain nirvana and gave special teachings to laywomen in addition to creating a nun’s order, he’s also on record as saying some pretty vile things about women.

When talking to his monks, the Buddha is quoted comparing women to creepers that entangle and then fell a tree, and to poisonous black snakes on account of their being “impure, foul-smelling, dangerous, traitorous to friends, frightening, wrathful, hostile, and double-tongued.”

The Buddha also warned his monks that it would be better for them to put their penises in the mouth of a cobra or a pit of hot coals than in a vagina. The Buddha was, it should be noted, talking to monks, who are sworn to celibacy and must uphold their vows or suffer the karmic consequences.

All in all, far from the caricature of easygoing, all-accepting blissfulness that has inspired a million head shops to adorn themselves with Buddha statues, the actual Buddha was a complex human being and a stern, sometimes unpalatable spiritual teacher whose views are not as easy to digest as many might think.

Intrigued by this look at the dark side of Buddhist teachings? Next, let’s answer the question “what is Tantra?” — and discover why it’s not what you think it is. Then, read up on six interesting religions you’ve probably never even heard of.