Despite being tried by two juries, Byron De La Beckwith was not convicted of murdering Medgar Evers in his own driveway in 1963 — until 30 years after the crime.

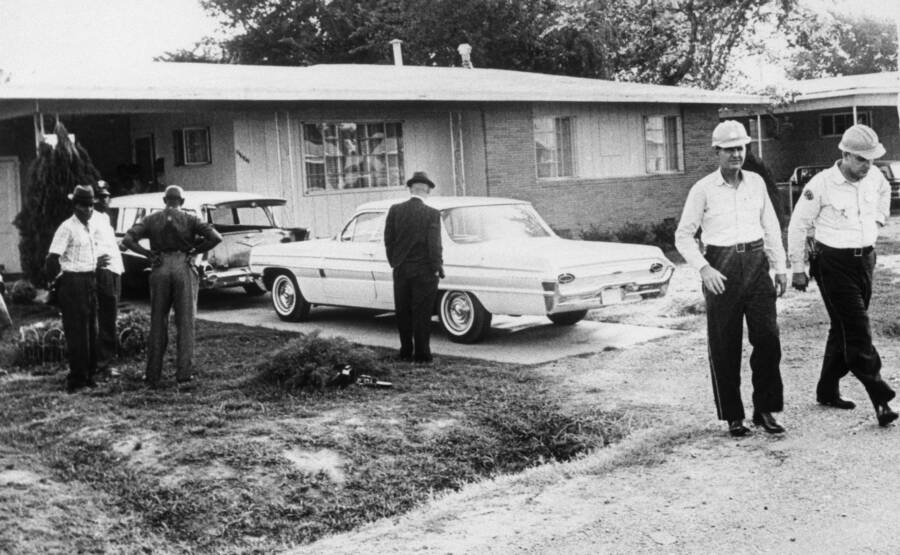

In the early morning of June 12, 1963, tragedy struck in the driveway of 2332 Guynes Street in Jackson, Mississippi. At around 12:30 a.m., white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith emerged from a patch of honeysuckle and gunned down civil rights leader Medgar Evers as he exited his car in his driveway.

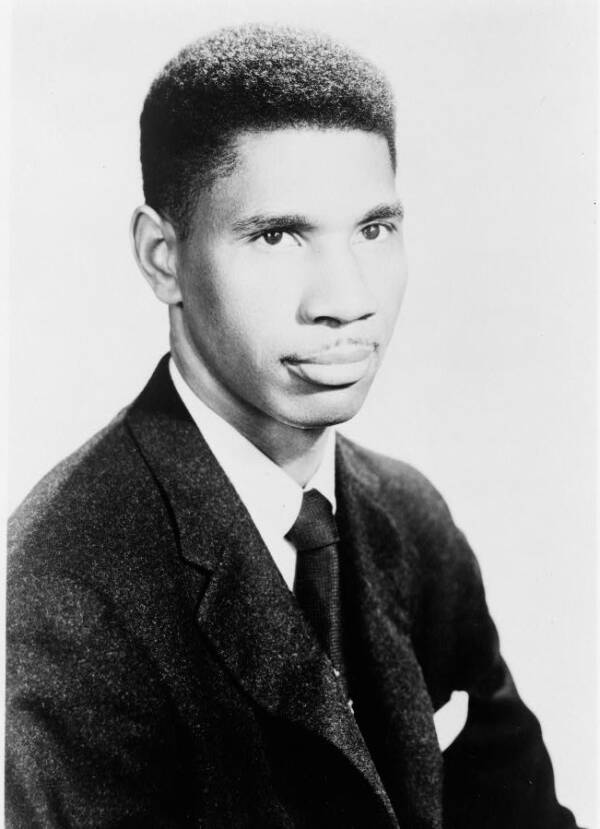

Appointed the NAACP’s first field secretary for Mississippi in 1954, 37-year-old Evers had risen to prominence with numerous civil rights campaigns in the state, including desegregation efforts in Mississippi parks and beaches, voter registration drives, and boycotts to integrate the state fair.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesByron De La Beckwith was convicted of the murder of Medgar Evers in 1994.

But these efforts also made him a target for the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan. And in the spring of 1963, the attacks on Evers increased in frequency and violence, culminating in Byron De La Beckwith’s cold-blooded murder.

But even though the evidence against Beckwith was overwhelming, he escaped conviction twice in 1964 due to hung juries. It wouldn’t be until the emergence of new evidence three decades later that Beckwith was finally convicted and sentenced to life in prison in 1994.

How Byron De La Beckwith Became A White Supremacist

Byron De La Beckwith was born on Nov. 19, 1920, in Colusa, California, the descendant of Confederate elites. In 1925, his father died of pneumonia, and his mother relocated them to Greenwood, Mississippi. Seven years later, his mother died of lung cancer, and he moved to his uncle’s home.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesByron De La Beckwith was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and joined the segregationist White Citizens’ Council in 1954 after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling.

Beckwith’s uncle wanted the best for him, so he sent him to The Webb School, one of the top private schools in the South. At 22, Beckwith became a Marine, served in World War II, and was honorably discharged.

He moved to Rhode Island, married, had a son with his first wife, Mary Louise Williams, and divorced soon after. Later, he married Thelma Lindsay Neff, and the pair moved back to Greenwood, where he became active in the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1954, Beckwith joined the newly-created White Citizens’ Council after the Supreme Court ruled that segregation was unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. According to a 1963 Time profile, he became so active in recruitment efforts for the pro-segregationist organization that its leaders had to ask him to stop.

“He tried to inject racism into everything,” a member of Beckwith’s church told Time. “If you talked about Noah and the Ark, he’d want to know if there were any Negroes in the Ark.”

Soon, under the direction of KKK Grand Wizard Sam Bowers, Byron De La Beckwith stood just yards away from one of Mississippi’s top civil rights activists, firing a single shot into Evers’ back that pierced his heart.

Why Medgar Evers Knew He Was A Target Of The KKK

Library of CongressMedgar Evers was NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi.

Medgar Evers’ life was primed to make him a leader in the civil rights movement. After being honorably discharged from the Army after serving in World War II, he enrolled at Alcorn State University, one of five HBCUs in the state, and met his future wife, Myrlie.

After his graduation, he worked with Dr. T.R.M. Howard in Mound Bayou in insurance. It was Dr. Howard who got Evers involved with the NAACP.

And following the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, he attempted to enroll in the segregated University of Mississippi Law School to study law as a test case for the organization, but he was denied because he was Black.

Instead, the NAACP hired Evers as their first field secretary in Mississippi. For the next nine years, Evers traveled up and down the highways taking reports of racism, violence, and terror that plagued Black Mississippians.

Evers, his wife, and three children moved to Jackson so he could have a basecamp to work with other influential leaders. They moved into a brightly colored teal house on Guynes Street in the north end of town.

The rise of racial violence against Black people in Mississippi kept Evers on the road more and more. And on the night of June 11, 1963, he met with NAACP lawyers while his family watched President Kennedy giving his Civil Rights Address on national television at home.

At the same time, Byron De La Beckwith crouched with his .30-06 caliber rifle across the street from Evers’ home, waiting in the shadows to kill the activist when he arrived.

Evers’ son, Darrel Evers, vividly remembers the night of the assassination. Speaking with The Los Angeles Times in 1994, he said, “We were ready to greet him, because every time he came home it was special for us. He was traveling a lot at that time. All of a sudden, we heard a shot. We knew what it was.”

Knowing he was a target of the KKK, Evers had taught the children safety drills, and they ran to hide in the bathtub when they heard the shot. Beckwith fired a single shot into Evers’ back as he made his way up the driveway. He died an hour later.

How Byron De La Beckwith Bragged About Killing Medgar Evers

Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesByron De La Beckwith stood across the street from Medgar Evers home and gunned him down as Evers exited the car.

Byron De La Beckwith was tried twice for the crime in 1964. And both times, the trials ended with hung juries, both of which were all-white since Black Mississippians were barred from voting or serving on juries.

For the next 30 years, Beckwith continued membership in the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations. In 1975, he was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder after he was arrested in New Orleans with guns, dynamite, and a map to the house of A.I. Botnick, the director of the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League.

And according to The New York Times, throughout the time that Beckwith was free, he frequently bragged about killing Medgar Evers, including at Klan rallies. His guilt was an open secret among white supremacists.

Then, in the 1980s, Jerry Mitchell, a journalist with the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, began digging into the coverage of the case, believing that something was missing.

According to NPR, Mitchell found evidence that the highest levels of Mississippi’s state government had aided Beckwith and his defense team during his first trials through tax-payer funded agency called the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission.

Mitchell reported that officials for the agency illegally screened prospective jurors for Beckwith’s trials to eliminate any who might convict him.

“The same time the state of Mississippi was prosecuting Byron De La Beckwith for the killing of Medgar Evers, this other arm of the state, the Sovereignty Commission, was secretly assisting his defense, trying to get Beckwith acquitted,” he said.

The assistance went all the way to the governor, who publicly sided with Beckwith, attended the trial, and infamously shook his hand before the jury began deliberations.

Ultimately, Mitchell’s research reopened the case against Byron De La Beckwith.

When Byron De La Beckwith Was Finally Convicted

William F. Campbell/Getty ImagesState troopers escort Byron De La Beckwith and his wife to court during Beckwith’s third trial in 1994 for the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers 31 years prior.

Though he tried to have the case dismissed, Byron De La Beckwith was brought to trial a third and final time in 1994. Prosecutors presented an Enfield .30-06 rifle with Beckwith’s fingerprints, new testimony from people who heard him brag about the murder, and all the original evidence the all-white jury ignored.

The jury, composed of eight Black and four white jurors, found Beckwith guilty of murdering Medgar Evers 31 years after he fired the fatal shot. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Beckwith attempted to appeal his case several times, citing that 31 years for a conviction violated his right to a speedy trial. The Supreme Court also denied his appeals. In 2001, Beckwith was transferred from the prison to a hospital, where he died after long battles with various illnesses on Jan. 21.

The work Evers did continued throughout the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and continues to inspire new generations of activists. In 2020, his home was designated a national historic site and a national monument under the National Parks Service. Visitors can tour Evers’ home and see what everyday life was like for the family and walk up the driveway where he was gunned down.

Though he was assassinated at just 37 years old, Medgar Evers’ legacy remains strong in Mississippi as a story of inspiration and action. Byron De La Beckwith’s name remains synonymous with the white supremacy that has plagued Mississippi for generations.

After reading about Byron De La Beckwith, explore the Civil Rights Movement in 55 powerful photos. Then, see these disturbing historical photos that reveal what it’s like to grow up in the KKK.