Exhibited as curiosities in the 19th century, conjoined twin brothers Chang and Eng Bunker were two of America's most infamous showmen.

Today, referring to conjoined twins as “Siamese twins” is considered rude and derogatory. But the term comes from the best-known conjoined twins in history: Siamese brothers Chang and Eng Bunker.

Born in Siam — present-day Thailand — Chang and Eng were connected at the sternum. Though their livers were fused together inside a short band of flesh, the twins otherwise had fully formed, separate bodies.

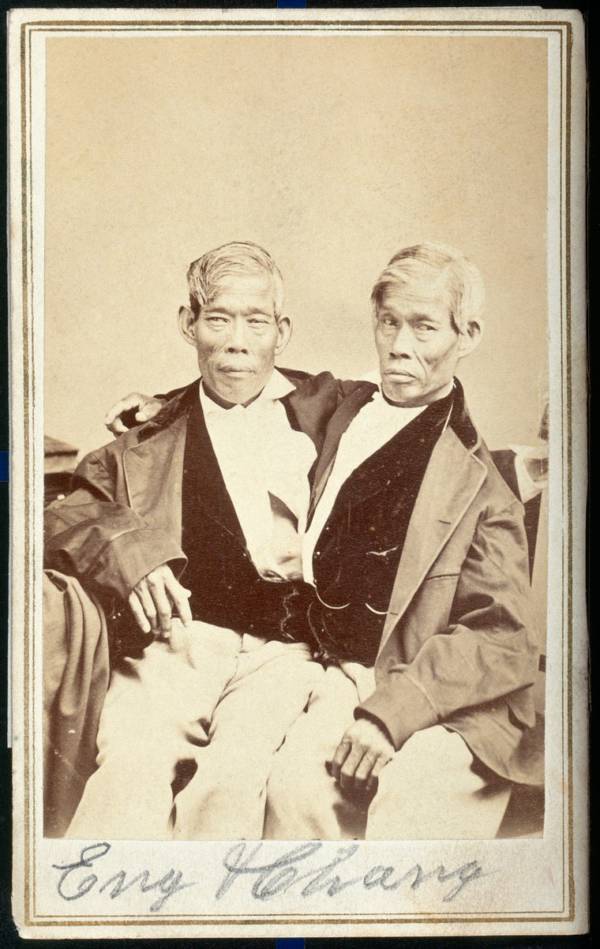

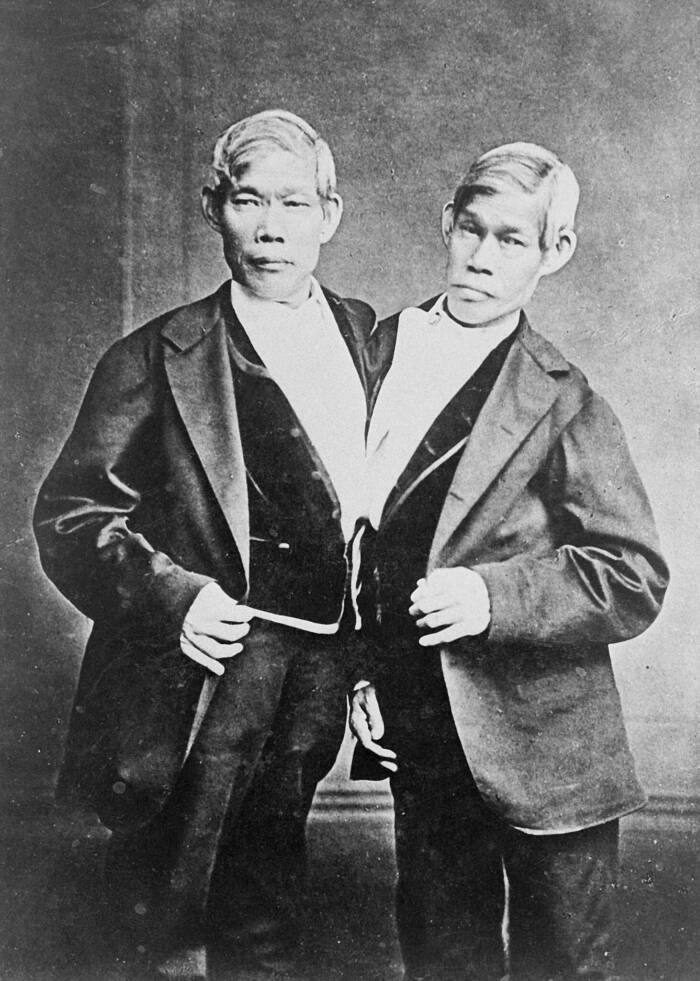

Wellcome CollectionChang and Eng Bunker became a sideshow sensation in the 1800s.

They spent most of their lives on display, traveling across the United States and appearing in “freak shows” during the 19th century. But Chang and Eng eventually took hold of their own destiny. Before they died at the age of 62, they’d married, established a successful farm, and had 21 children.

The “Siamese Twins” Leave Siam

Born on May 11, 1811, in Siam, Chang and Eng Bunker drew attention from the start. In a biography of the twins called Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous With American History, author Yunte Huang writes that the boys were initially seen as “evil omens.” The king of Siam even ordered their deaths, but apparently never sought to reinforce his order.

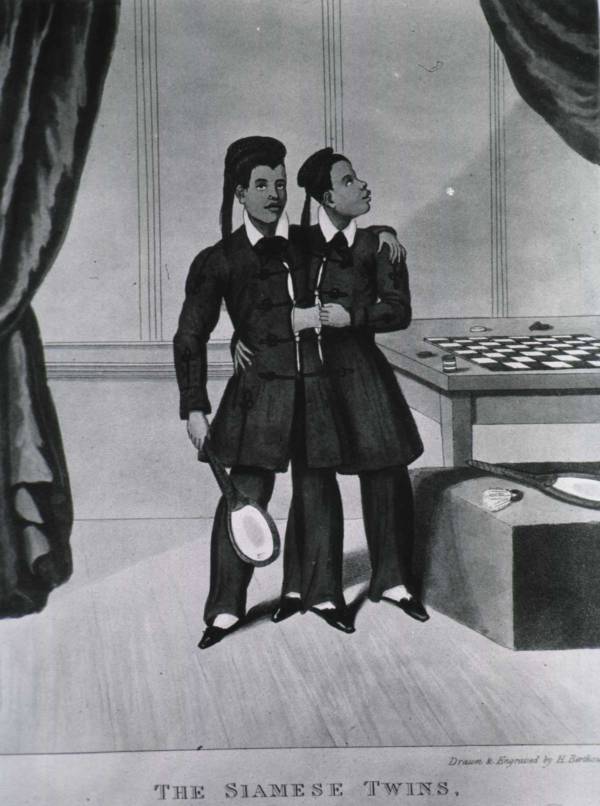

H. Berthoud/Wikimedia CommonsChang and Eng, illustrated when they were about 18 years old.

Instead, the boys grew up in relative peace along the Mekong River. They spent their days selling duck eggs, and many nights swimming in the river, which is where Scottish businessman Robert Hunter first spotted them.

To Hunter, they seemed like characters in a Greek myth. Furthermore, the twins seemed like a ticket to money and fame. But the king of Siam refused to let the boys leave the country. It took Hunter five years to convince him, and the king agreed to let them go on a five-year tour in 1829.

With a small suitcase in hand, Chang and Eng Bunker boarded a ship to Boston. They would never return to Siam or see their family again.

Chang And Eng Bunker Tour The World

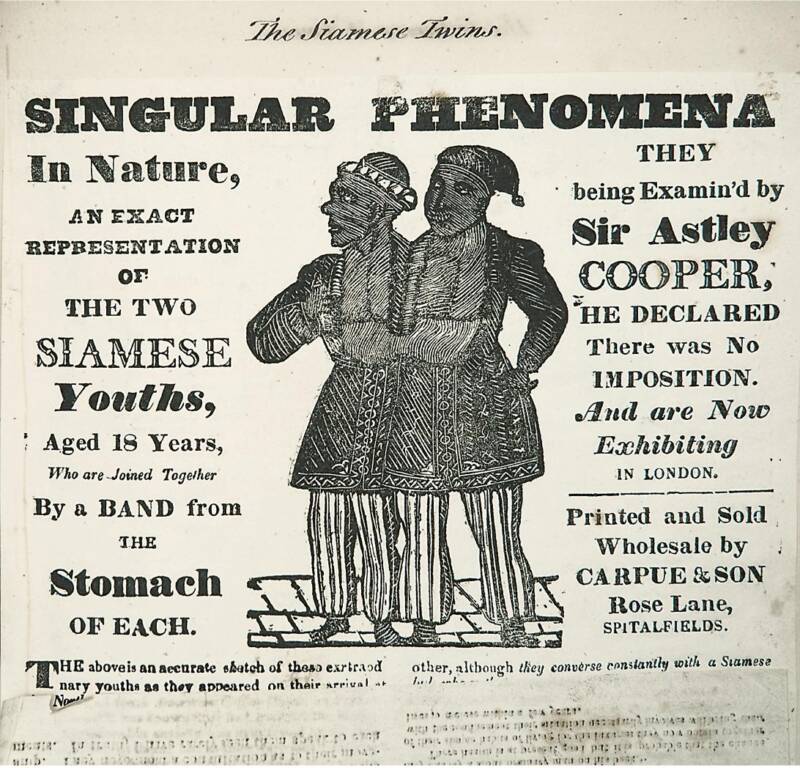

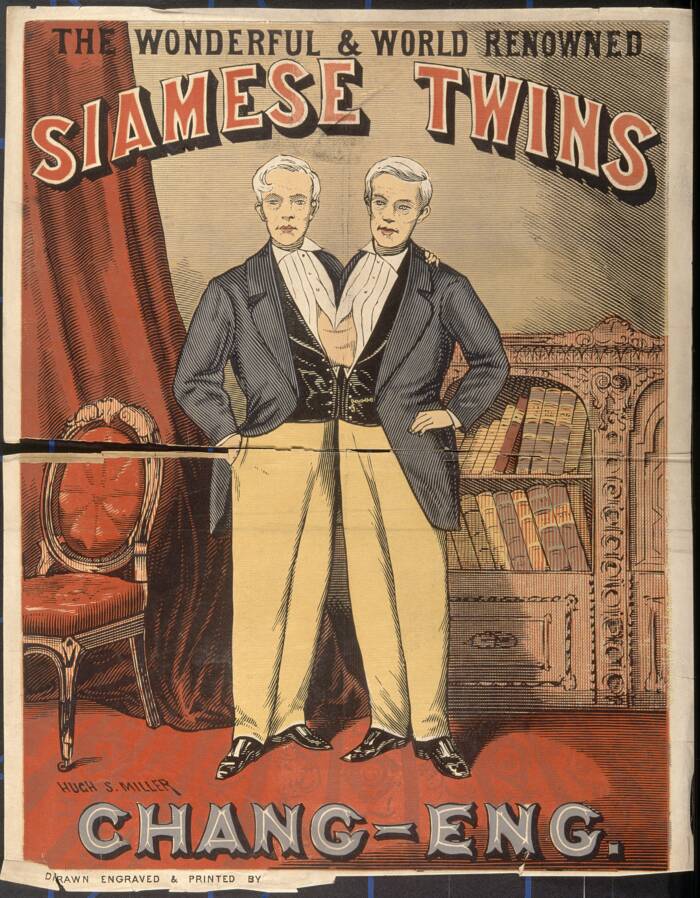

National Library of MedicineA poster promoting a show featuring Chang and Eng Bunker.

Though they had been called “Chinese twins” in Siam — their father was Chinese and their mother was Chinese and Siamese — Chang and Eng were dubbed the “Siamese twins” when they arrived in the U.S., according to NPR.

There, they were subjected to a variety of tests. According to The Lives of Chang & Eng: Siam’s Twins in Nineteenth-Century America by Joseph Andrew Orser, one American doctor examined the fleshy band that connected them, and discovered that they both felt pain near its center. However, on either side of the center, only one twin felt pain. The doctor also noted that “when one brother experienced a sour taste in his mouth, the other did as well,” and that “tickling one of them resulted in the other demanding a stop to it.”

In the U.S. — and also in Europe — the two 17-year-olds were also put on public display. They were not part of a larger “freak show,” but billed as one attraction. Their show originally consisted of physical acts like backflips. But as they began to learn how to speak English, the Bunker brothers also started interacting with the audience by talking and answering questions.

They also became determined to break out on their own as performers. As Yunte Huang told NPR, they had been “tricked” into signing an exploitative contract with Hunter and an American ship captain named Abel Coffin.

Though Hunter eventually sold his share, Coffin remained in charge of the twins until 1832. Then, Chang and Eng turned 21 and declared their independence, pointing out that they had been mistreated and that Coffin had pocketed the money they’d made from their shows.

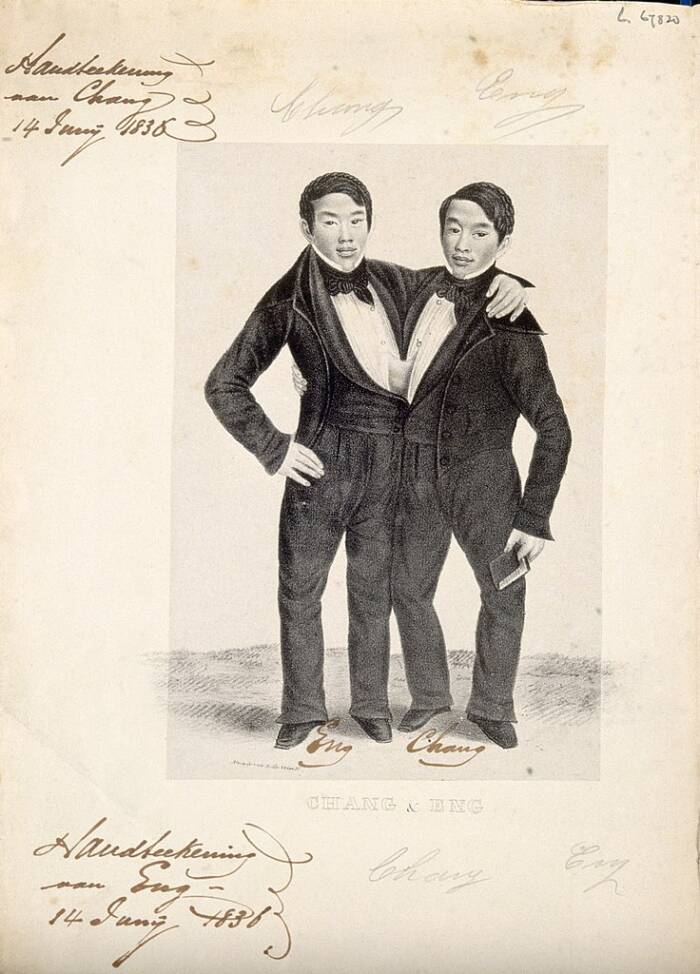

Wellcome CollectionChang and Eng Bunker broke out on their own in 1832, though they continued touring for several years.

Until 1839, Chang and Eng Bunker toured independently with the help of a manager they’d hired, Charles Harris. They made enough money to buy property, and decided to settle down in Traphill, North Carolina, where they purchased land and started building a house. The twins also became naturalized American citizens and adopted the last name “Bunker.”

While residing in North Carolina, the Bunker twins came to embrace a traditional Southern lifestyle — in more ways than one.

The Bunker Twins’ Family Life

After settling down in North Carolina, Chang and Eng Bunker got married to two sisters, Adelaide and Sarah “Sally” Yates, in 1843. By that point, the brothers had known the Yates family for years. But the marriage still raised eyebrows — and some fierce objections — in the pre-Civil War society.

Wikimedia CommonsChang and Eng Bunker photographed with their wives, Adelaide and Sarah, and two of their sons. Circa 1865.

According to Orser’s book, newspapers in the North and South reported on the marriage, often in mocking or negative terms. Not only were Chang and Eng marrying white women, but they were also seen as “freaks” by many in the country. When the couples went riding through town in an open wagon, one local paper reported that “all hell broke loose” among residents.

“A few men ‘smashed through some windows at [Mr. Yates’] farm house,'” while others “threatened to burn his crops,” the paper reported.

That said, the wedding went forward. In celebration of the marriage, the Yates family even gifted the Bunker twins with an enslaved woman named Grace Gates. She was the first of many people who would be enslaved by Chang and Eng, who had once been effectively enslaved themselves. (In all, the brothers enslaved at least 18 people, many of whom were children.)

At first, the couples shared one home — and one marital bed — but in an effort to live separate lives, they decided to build two houses on another piece of land. As Huang tells NPR, the couples would split their time as such: Three days were spent with Chang’s wife in Chang’s home, and then three days were spent with Eng’s wife in Eng’s home. Chang and Adelaide eventually had 10 children, and Eng and Sarah had 11 kids.

“With Chang and Eng it was never really documented how they conducted themselves in a sexually intimate way, but it is interesting to note that when the wives had their children, they delivered only maybe four or five days apart, which suggests some kind of coordination,” Craig Glenday, the Guinness World Records Editor-in-Chief, remarked.

Public DomainChang and Eng Bunker with their wives, 18 of their children, and Grace Gates, one of the enslaved people on their farm.

Huang suggested that the twins practiced “alternate mastery.” Used by other conjoined twins, it means that one twin can dissociate — sometimes while napping or reading a book — while the other goes on dates or has sex.

In all, it seems that Chang and Eng Bunker had succeeded in establishing normal lives outside of the spotlight. The Raleigh Register even wrote approvingly in 1853 that the twins were “altogether American in feeling.”

But things turned bleak for the twins after the Civil War.

The Deaths Of Chang And Eng Bunker

When the Civil War broke out, Chang and Eng Bunker wholeheartedly supported the Confederacy. They invested financially in the Confederate cause, and the American Battlefield Trust reports that two of their sons even became Confederate soldiers during the conflict.

But when the war ended, the Bunker family was financially ruined. Not only had they poured much of their resources into the conflict, but they could no longer rely on the labor of enslaved people to run their farm. With little choice, Chang and Eng Bunker went back on the road to tour again.

Wellcome CollectionA poster of Chang and Eng Bunker from later in their career.

They traveled throughout the United States — where Northern audiences were less than enthused to support ex-Confederates — and Europe. By this point, the twins were in their 50s. And touring started taking its toll.

On their journey back from Europe in 1870, Chang suffered from a paralytic stroke. He was paralyzed on one side of his body, which meant that the twins’ touring career was effectively over. It also limited their mobility, as Chang had to use a crutch and depend heavily on his brother.

Chang, already a heavy drinker, became more reliant on alcohol to lift his mood, and his health began to suffer even more. Though Eng never drank (and never appeared to be drunk when his brother indulged in booze), he seemed to be aging faster, and many believed that Eng looked at least five years older than Chang. Despondent and frustrated, the twins began to seriously consider surgical separation for the first time in their lives.

But this would never come to pass. On January 17, 1874, Chang died in his sleep at age 62, likely from a blood clot in his brain.

Eng awoke to find his brother dead, and knew that death would soon find him, too. He reportedly cried out, “Then I am going!” As Huang told NPR, Eng’s final hours were probably “horrifying.” Though the twins had planned to be separated if one died, the doctor didn’t get there in time.

Public DomainChang and Eng Bunker in their later years. They lived until the age of 62.

A few hours later, Eng died too. Doctors at the time surmised that he’d died of shock, though some believe he may have died from blood loss as the circulatory system he shared with his brother failed.

Yet the story of Chang and Eng Bunker does have one final chapter.

An Eternity In Plaster

After their deaths, Chang and Eng Bunker’s bodies were dissected and photographed. Their remains were rushed off to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where their bodies were pulled apart and studied.

Examining the fleshy band that connected them, which had stretched to be over five inches long, doctors determined that separating the twins would have been fatal. They were connected at the liver, and would have certainly died if the band had been severed. (It’s believed that the modern medical technology of today could have potentially separated them.)

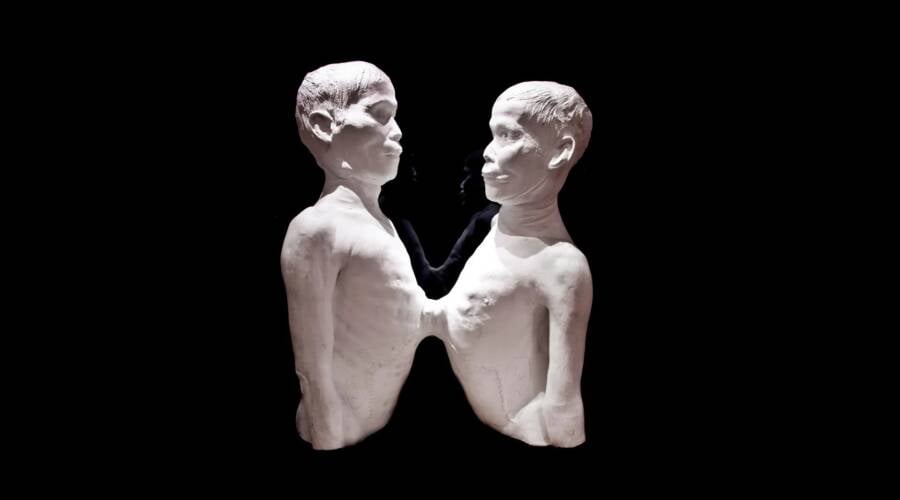

Mütter MuseumChang and Eng immortalized in a plaster death cast.

In death, the Bunker twins left behind an incredible legacy. Side by side, the twins from Siam came to the U.S., won their freedom, and established normal lives. They became citizens, married, and had children.

They also inspired a story by Mark Twain, a novel by Darin Strauss, a play by Philip Kan Gotanda, and were featured in the movie The Greatest Showman. Plus, they inspired the (now largely defunct) term “Siamese twins.”

Today, they have more than 1,500 descendants, many of whom still meet up at family reunions. Some have gone on to accomplish incredible things — like the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Caroline Shaw.

And Chang and Eng Bunker themselves are still together in a way, eternally linked in a death cast on display at the Mütter Museum.

Together was the only way they could ever be in their time.

After learning about the incredible lives of Chang and Eng Bunker, check out some of P.T. Barnum’s most famous oddities. Or, look through these stunning photos of vintage sideshow performers.