On September 29, 1982, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman of Chicago died after taking Extra-Strength Tylenol laced with cyanide — and six other victims soon followed.

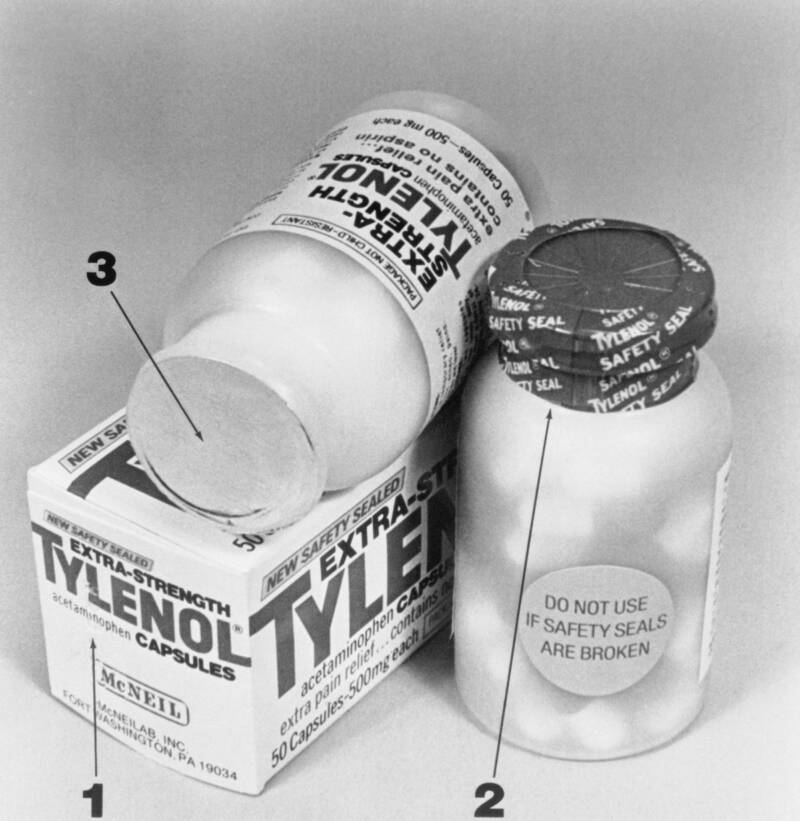

Bettmann/Getty ImagesAfter a string of people died taking Tylenol pills that were laced with cyanide, the FDA invented tamper-proof packaging for medications.

In 1982, Chicago experienced a wave of unexplained deaths in a gruesome case that’s now known as the Tylenol murders.

Between Sept. 29 and Oct. 1, 1982, seven healthy people ranging in age from 12 to 35 died suddenly. The only thing they had in common was that they had all taken the popular over-the-counter pain reliever Tylenol moments before they fell ill.

An investigation soon revealed that the victims’ Tylenol had all been laced with cyanide, but exactly how the poison made it into their bottles — and who put it there — remains unsolved to this day.

The Victims Of The Chicago Tylenol Murders

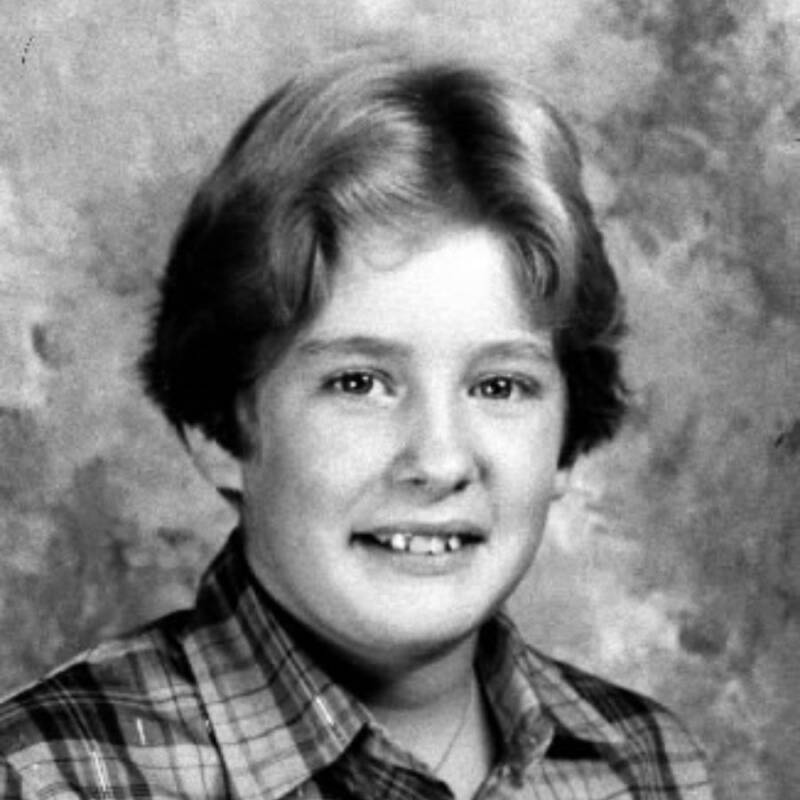

Around 6:15 on the morning of Sept. 29, 1982, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman woke up feeling too sick to go to school. Before going back to bed, she decided to take a capsule of Extra-Strength Tylenol to soothe her sore throat. “I heard her go into the bathroom,” Kellerman’s father told the Chicago Tribune in October 1982.

“I heard the door close. Then I heard something drop… I opened the bathroom door, and my little girl was on the floor unconscious. She was still in her pajamas.”

FindAGraveMary Ann Kellerman, the first — and youngest — victim of the Tylenol murders.

Mary was rushed to the hospital, but she was pronounced dead less than four hours later.

An hour after Mary’s death, a 27-year-old postal worker named Adam Janus stopped at the grocery store to buy some flowers for his wife, and he picked up a bottle of Tylenol while he was there. When he got home, he took two capsules — and almost immediately collapsed. Again, he was rushed to the hospital, where doctors tried to revive him. He died just after 3 p.m.

Tragically, the Janus family’s misfortunes weren’t over. As Adam Janus’ loved ones gathered at his home to comfort his wife later that very afternoon, his 25-year-old brother, Stanley, felt a headache coming on. He grabbed the same bottle of Tylenol that Adam had purchased that morning and offered a pill to his wife of three months, 20-year-old Terri.

Just after swallowing two capsules of Tylenol, Stanley stated, “My God, I feel bad.” He fell to the floor, his family called 911, and paramedics arrived and began working on him. When Terri collapsed as well, emergency officials initially assumed she had fainted from distress. However, they would soon realize that she had also been stricken by the same mysterious ailment that took her husband and brother-in-law.

Around the same time, Mary “Lynn” Reiner, who had just given birth to a baby boy six days prior, took a Tylenol before feeding her son. The 27-year-old woman fell to the kitchen floor and began seizing.

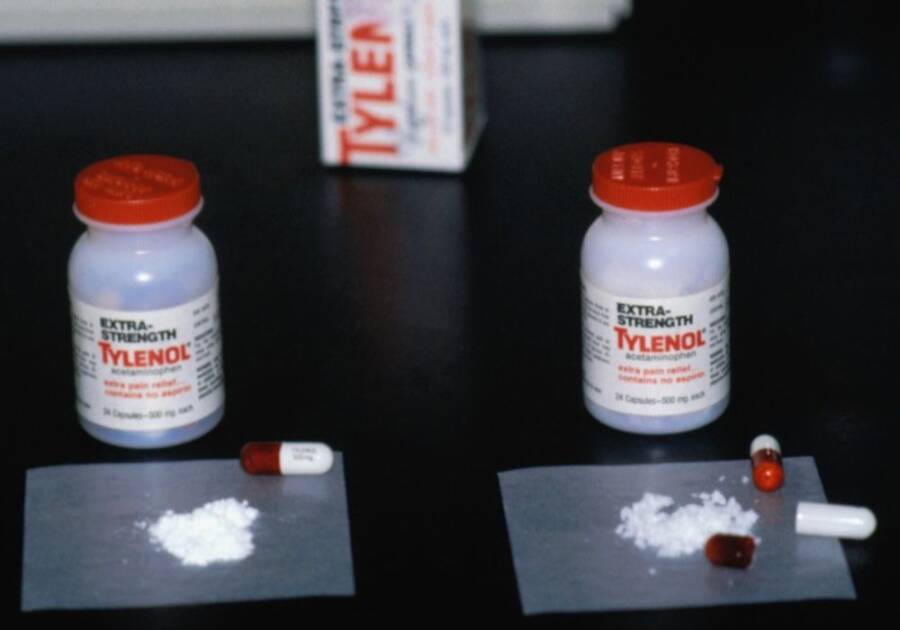

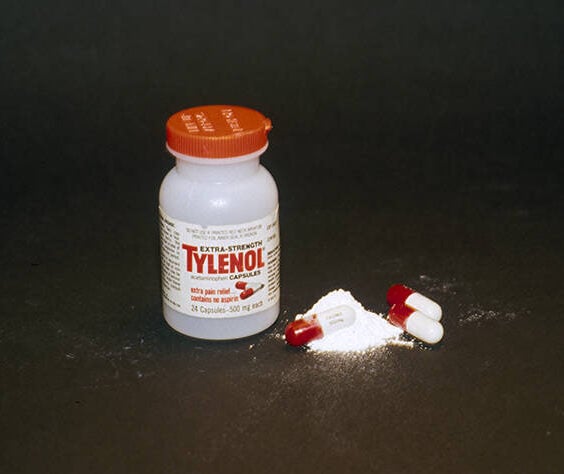

X/@CrimeAndCoffee2The culprit opened capsules of Tylenol, dumped out the powdered acetaminophen inside, and replaced it with cyanide. Here, the normal Tylenol (left) is pictured next to the poisoned capsules.

At 6:45 p.m., 31-year-old single mother Mary McFarland swallowed two pills in the break room of her job at a shopping mall on the outskirts of Chicago. As her co-worker Diana Hilderbrand later recalled to the Chicago Tribune, “I don’t know if it was even 10 minutes later. She said, ‘I don’t feel good,’ and she just collapsed.”

And at 9:16 p.m., 35-year-old flight attendant Paula Prince purchased a bottle of Extra-Strength Tylenol from a Walgreens on her way home from Chicago O’Hare International Airport. She took one before going to bed. Her sister and her friend found her dead in her condo two days later.

Stanley Janus died the night of Sept. 29, and his wife Terri was removed from life support on Oct. 1. Reiner and McFarland were both pronounced dead on Sept. 30. In less than 24 hours, five bottles of Tylenol had taken the lives of seven healthy people. But how?

The Investigation Into The Mysterious Deaths

The first person to make the connection between the deaths and the Tylenol was a nurse named Helen Jensen. She told officials with the medical examiner’s office about her theory — but they didn’t believe her.

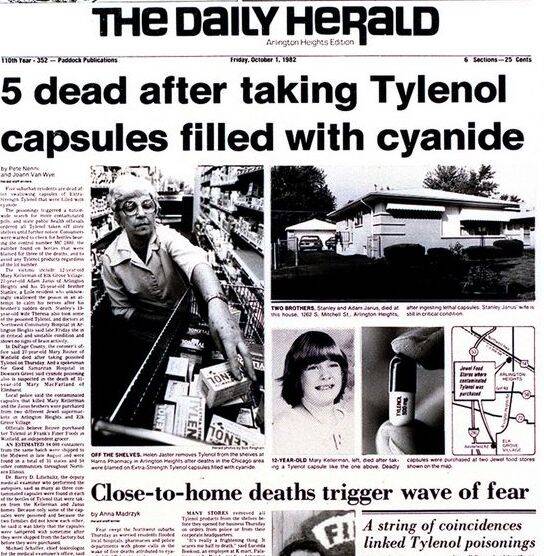

The Daily HeraldHeadlines about the Chicago Tylenol murders at the time they happened.

As police continued to investigate the deaths, however, it became clear that Jensen was correct. On the morning of Sept. 30, they began driving through the streets of Chicago with bullhorns ordering people to throw away any Tylenol in their medicine cabinets. Public health workers went door to door with flyers, and stores began pulling all Tylenol from their shelves.

Officials had realized that something was wrong with the Tylenol — but they didn’t know what yet. The bottles that Mary Kellerman and the Janus family had taken their pills from had been sent off for testing, but even before the results came back, Dr. Thomas Kim surmised that the Tylenol capsules had to have been tainted with cyanide. Nothing else would have killed the victims so quickly.

Meanwhile, Tylenol manufacturer Johnson & Johnson issued a nationwide recall of 31 million bottles of the pills. It was the first mass recall in U.S. history.

An employee removing Tylenol from store shelves.

In the end, a drawn-out investigation revealed that the cyanide contamination had not occurred within the Johnson & Johnson facilities, because some of the contaminated bottles had come from different suppliers. So, how did the poison get inside the Tylenol capsules?

Police eventually determined that the culprit must have purchased the bottles of Tylenol, contaminated them at their home, and then returned them to the store shelves, where the victims purchased them.

Though the case was highly publicized nationwide, investigators never caught the person responsible. However, there was one man who remained the prime suspect for decades: James William Lewis.

Soon after the Tylenol murders, Lewis had sent a letter to Johnson & Johnson asking for $1 million if they wanted the poisonings to stop. He was later convicted of extortion and sentenced to 20 years in prison — but there was no physical evidence connecting him to the deaths, and he later denied any connection to the incident.

The Invention Of The Tamper-Evident Seal

Though the culprit involved in the Chicago Tylenol murders was never caught, the deaths and subsequent investigation sparked a significant change in the manufacturing and packaging of Tylenol.

Bernard Bisson/Sygma via Getty ImagesThe makers of Tylenol introduced solid pills and tamper-evident seals following the murders.

The capsules were reintroduced, but so were solid pills that were much harder to contaminate — along with a new tamper-proof package. In addition to the new seals, tampering itself was made illegal. Congress passed the “Tylenol bill” that made it a federal offense to meddle with consumer products in 1983. This resulted in one individual being sentenced to 90 years in prison for a copycat crime of the Tylenol murders.

Though the initial response to the scare was to stop purchasing Tylenol, Johnson & Johnson quickly turned the incident into a rebranding, and the company’s reaction was widely heralded as one of the best responses to a corporate crisis in history.

Indeed, just two months after the horrific deaths, Johnson & Johnson’s stock soared past where it had been before the mysterious Tylenol murders.

Now that you’ve read about the Chicago Tylenol murders, learn about the history of Aqua Tofana, the poison 17th-century Italian women used to kill their husbands. Then, discover how the U.S. government once killed thousands of people by poisoning alcohol during Prohibition.