Inside the CIA's Cold War-era plans for mind control, psychic spies, and one horrifying cat.

Dennis Skley/Flickr

Most folks might scoff at the idea that the American government would kidnap its own citizens and brainwash them with alternating rounds of torture and LSD — but that’s exactly what the CIA did from 1953 to 1973.

The CIA brainwashing project was called MK Ultra, and it was enormous. At least hundreds of researchers at 80 institutions spent millions of dollars over the project’s 20-year lifespan, using techniques ranging from sleep deprivation to shock therapy, killing several unwilling test subjects along the way.

Finally, in 1973, CIA Director Richard Helms — who had helped run MKUltra earlier in his career — halted the project, officially meant to garner information on how to resist torture, and ordered that the files be destroyed. The surviving documents provide just a glimpse of the project’s vast scope.

More on that later, though. Right now, it’s time to talk about psychic surveillance and robotic spy cats.

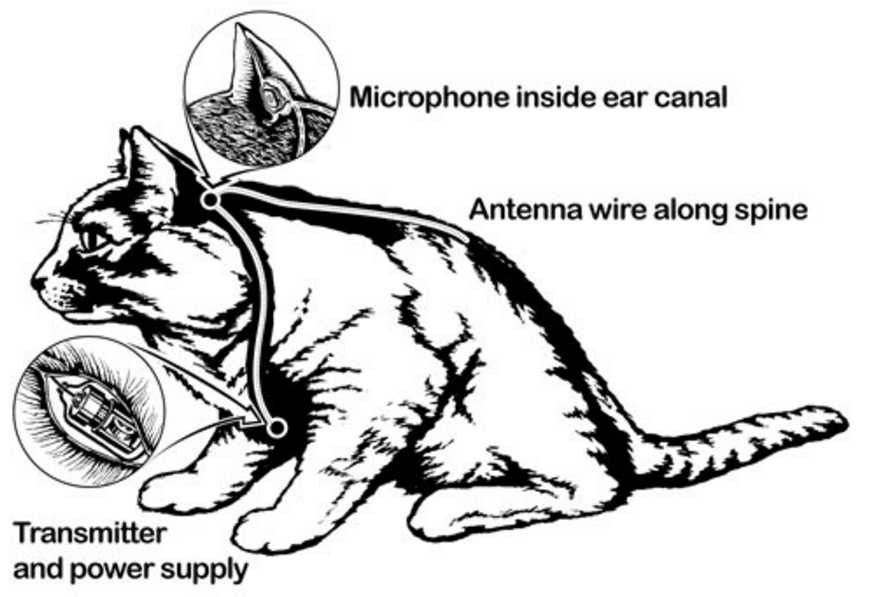

Acoustic Kitty: Spy Cats

Gizmodo

Turns out spy movies are not wrong: The best way to have a clandestine conversation is out in public. No matter how soft you speak indoors, there’ll always be a bug or two in the embassy room. Which is why, in 1961, the CIA launched project Acoustic Kitty to build a team of spy cats.

These “spy cats” would be wired to pick up sound. And it worked — sort of.

“They slit the cat open, put batteries in him, wired him up. The tail was used as an antenna. They made a monstrosity,” said Victor Marchetti, an executive assistant to the CIA director during the 1960s. He relayed this to author Jeffrey Richelson, who included Marchetti’s account in his 2001 book, The Wizards of Langley.

Then it came time to test the cat, which they did outside the Russian embassy. And that’s when it ended. As Marchetti tells it:

“They tested him and tested him. They found he would walk off the job when he got hungry, so they put another wire in to override that. Finally, they’re ready. They took it out to a park bench and said, ‘Listen to those two guys. Don’t listen to anything else – not the birds, no cat or dog – just those two guys!’ They put him out of the van, and a taxi comes and runs him over. There they were, sitting in the van with all those dials, and the cat was dead!”

Later, a case officer went back later to scoop the cat’s remains into a box, and the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology wrote a post-mortem wherein it praised the scientists involved for their hard work, but concluded that building spy cats just wasn’t practical.

You can read part of the official — redacted — report here.

Stargate Project: Remote Viewing

MICHEL GANGNE,PASCAL GUYOT/AFP/Getty ImagesSaudi soldiers examine the debris of an Iraqi Scud missile that landed in downtown Riyadh on January 22, 1991 after being intercepted by US countermeasures. Allegedly, CIA psychic spies helped locate scud missiles like these during the Gulf War.

You may have seen George Clooney attempt to kill a goat with his mind in the 2009 film The Men Who Stares At Goats. But like the film’s opening credits say: More of this is true than you would believe.

Though neither that film nor the book upon which it was based mention Stargate Project by name, both took inspiration from that indeed real government project that sought to train a group of psychic spies for remote viewing (using extra-sensory perception to surveil a target without actually being physically at or near that target).

With such a top secret mission at hand, only the chairman and ranking members of the Senate and House Appropriations and Armed Services Committees knew of Stargate Project’s existence, which began in 1978.

Befitting such an off-the-grid operation, the project operated out of dilapidated, leaky wooden barracks somewhere in Fort Meade, Maryland. By all accounts, it was a miserable work environment.

Nevertheless, according to some project members at least, they accomplished some truly extraordinary things.

The Washington Post spoke to one project member, Joseph McMoneagle, who was with Stargate from its inception all the way until 1993. As the Post writes, McMoneagle claims that he and other project operatives used their remote viewing abilities to “help locate American hostages, enemy submarines, strategic buildings in foreign countries and who knows what else.”

Typically, the powers that be would give McMoneagle a sealed envelope containing a photo or document and ask him to use his remote viewing skills to provide more information about the subject of said photo or document. For example, McMoneagle’s superiors might provide him with a photo of a man and expect him, using only the powers of remote viewing, to discern where that man was currently located.

Among his more than 450 such missions, McMoneagle claims to have helped the Army locate hostages in Iran, predict where the infamous Skylab station would crash back to Earth, and pinpoint scud missiles during the Gulf War.

Through it all, McMoneagle states that the unit had a success rate of 15 percent, which, as he tells it, is better than plenty of other methods of intelligence gathering.

“Everybody’s got it all backward,” McMoneagle told The Washington Post, referring to the criticism and ridicule Stargate Project received after the CIA shut it down in 1995 and declassified the report that dealt the killing blow. “The project was approved on a year-to-year basis. This approval was based on our performance. So why the hell are they running for cover now?”

But run for cover is precisely what the CIA ultimately did.

The organization had first shut down an earlier remote viewing program in 1975 before Stargate began its run, over the course of which its administration was shuffled between agencies. Stargate then fell to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the Department of Defense group that gathers intelligence to be used in foreign combat missions. Stargate lived with the DIA until 1994, at which point the CIA scooped it up, realized it had egg on its face, and ordered a report done on the unit’s effectiveness.

That report found that “remote viewing, as exemplified by the efforts in the current [Stargate Project] program, has not been shown to have value in intelligence operations.” The report furthermore claimed that Stargate’s findings were irrelevant and erroneous, and that project managers may have been changing the data gathered from remote viewing after the fact with the helpful hand of hindsight.

However, one of the report’s authors, UC Davis statistics professor and parapsychologist Jessica Utts, took the dissenting and ultimately marginalized position that remote viewing did in fact work.

Utts, a longtime remote viewing proponent and board member of the International Remote Viewing Association, wrote in the report that:

“At this stage, using the standards applied to any other area of science, the case for psychic functioning has been scientifically proven. It would be wasteful of valuable resources to continue to look for proof. Resources should be directed to the pertinent question about how this ability works.”

On the other hand, the report’s other author, University of Oregon psychology professor Ray Hyman wrote:

“Where parapsychologists see consistency, I see inconsistency. Where Utts sees consistency and incontestable proof, I see inconsistency and hints that all is not as rock-solid as she implies.”

In the end, the CIA sided with Hyman, not Utts, and shut the project down in 1995.

At its peak, the Stargate Project employed 22 people. By the end, only three remained. For all their efforts, the project cost the U.S. government $20 million for the privilege of having merely a last-ditch, everything-is-exhausted, option in intelligence gathering.

MKUltra And Operation Midnight Climax

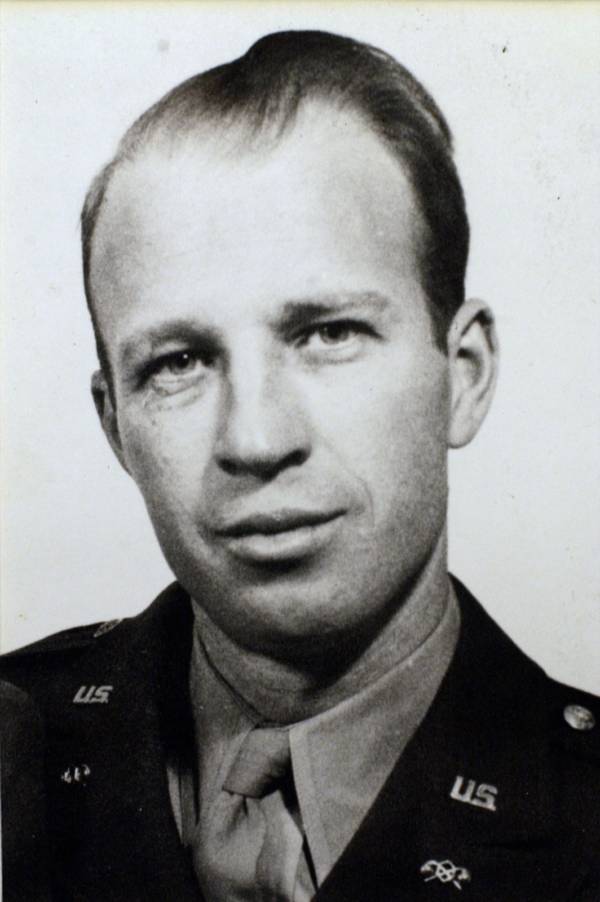

Baltimore SunFrank Olson, the CIA operative whose death during Operation Midnight Climax helped brings its parent project, MKUltra, to light.

While MKUltra grouped together dozens of different CIA projects involving mind control and drugs, namely LSD, one of the few projects for which we have compelling surviving evidence is Operation Midnight Climax — and why not be at least a little bit coy when you’re using government money to pay prostitutes to drug unsuspecting victims for purposes of interrogation and mind control.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the project operated in two main cities: San Francisco and New York City. The CIA destroyed the New York files, but due to a bureaucratic snafu, the San Francisco files survived, allowing all a glimpse at this audacious project.

The operation went something like this: The CIA would secure rooms with one-way mirrors, install microphones and listening devices into the walls, and hire prostitutes. These prostitutes would then lure men back to the safe houses and dose them with LSD. The men would flip out, and the CIA operatives would study their behavior from behind the mirror, allegedly with a pitcher of martinis nearby, and interrogate the men to see how effective LSD could be as a kind of truth serum.

While the project did yield a few significant findings (i.e. men were more likely to spill secrets after the deed than before), that was about it. In fact, the main thing Operation Midnight Climax proved was how useless LSD was in loosening a person’s tongue. Indeed, the unpredictable drug was actually more likely to have the opposite effect and cause the subject to clam up.

In some cases, however, things got much, much worse.

Wayne Ritchie, a former U.S. Marshal, claims he was made a victim of Operation Midnight Climax after being dosed with LSD during a 1957 holiday party. The San Francisco Weekly wrote up his description of what happened next:

The room began to spin. The red and green lights on the Christmas tree in the corner spiraled wildly. Ritchie’s body temperature rose. His gaze fixed on the dizzying colors around him…He came unglued. Ritchie feared the other marshals didn’t want him around anymore. Then he obsessed about the probation officers across the hall and how they didn’t like him, either. Everyone was out to get him. Ritchie felt he had to escape.

Deep under the influence, Ritchie robbed a bar later that night using two service issue revolvers. He was caught, pled guilty, and, despite his otherwise clean record and the obvious extenuating circumstances, forced to resign from the U.S. Marshals office.

He would work as a painter for the next 34 years. In the 2000s, he tried suing the government but the court ultimately dismissed the case. The surviving deposition of Ira Feldman (a member of the Midnight Climax staff), however, shows the callousness with which the project operated:

[Ritchie’s attorney:] Now, all these people that you personally drugged, you never did any follow-up on them, in the sense of telling them that you had drugged them, did you?

[Government attorney:] Objection. Lacks foundation. Go ahead and answer it, if you can.[Feldman:] Not all the people that I drugged. I drugged guys involved in about ten, twelve, period. I didn’t do any follow-up, period, because it wasn’t a very good thing to go and say “How do you feel today?” You don’t give them a tip. You just back away and let them worry, like this nitwit, Ritchie.

[Ritchie’s attorney:] When you say “let them worry,” you mean let them have a head full of LSD and let —

[Feldman:] Let them have a full head, like what happened, like what happened with this nut when he got out and got drunk.

By 1963, six years after Ritchie and plenty more cases like his, the government scaled down the sanctioned brothels after the top brass at the CIA began to change. The organization shut down the San Francisco operation completely in 1965, then pulled the plug on New York the following year.

The one prominent fact known about the New York City operation is that in 1953 government hands dosed CIA biological warfare scientist Frank Olson with LSD, who then suffered from extreme anxiety and paranoia. Nine days later, he died after falling from a 13th floor window of the Hotel Statler — some say he jumped, some say he was pushed.

Olson’s family alleged that the government killed him because he was attempting to leave the CIA for good. According to the family, Olson may have threatened to expose secrets relating to biological warfare during the Korean War. In 1976, Olson’s family settled out of court with the U.S. government for $750,000.

This case and the other extant material related to Operation Midnight Climax served as the main evidence that the morass of projects known as MKUltra ever happened.

Next, read about the government conspiracy theories that turned out to actually be true, and then have a look at the four most sinister programs the CIA ever implemented.