Just south of San Francisco, there lies a little town called Colma where the dead outnumber the living 1,000 to 1.

Wikimedia Commons

Colma, California is a bright green expanse of manicured lawns and small white buildings nestled inside the crowded tangle of communities that make up the San Francisco Peninsula. It’s easy to spot from the air as a large splotch of seemingly underdeveloped land paradoxically squatting next to some of the most expensive and in-demand real estate on Earth.

Driving through town, quiet country roads wend past neatly kept residential neighborhoods and a single school that serves the children of Colma’s roughly 1,800 residents. At first glance, the town seems idyllic and peaceful, if a bit heavy on cemeteries.

At second glance, Colma actually does have quite a few cemeteries. Like, a lot. Way too many for such a small place. Every major street seems to connect to a cemetery, necropolis, columbarium, or other polite suburban Californian term for a corpse dump.

The last time anybody counted, the town had 17 graveyards with something like two million individual graves and tombs for people who died and were buried sometime in the last century. Who these people were and how they got to sleepy little Colma reveals a lot about San Francisco’s early growing pains.

Colma: Growing Pains Of A Dynamic Young City

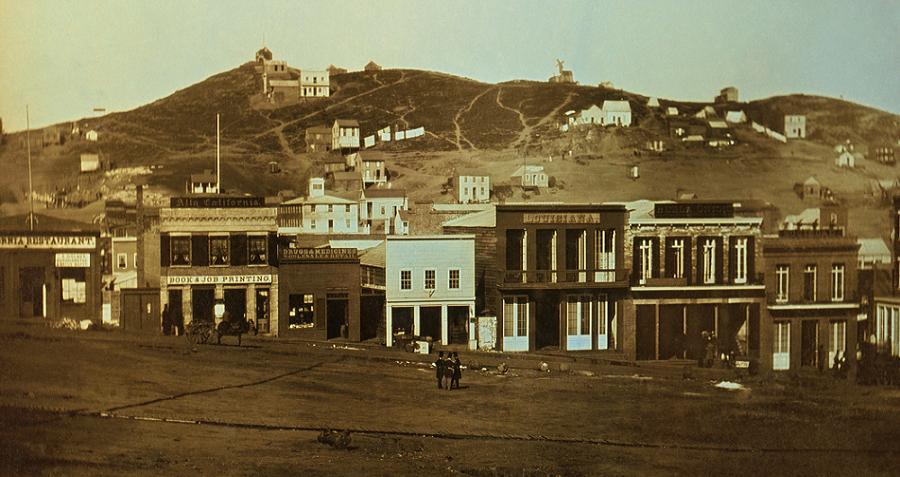

Wikimedia CommonsPortsmouth Square, San Francisco, in 1851. The city never had much room to grow, and cemeteries were a luxury item in the tight quarters. This picture was taken from where the Pyramid now stands, facing toward what is now the Cultural Center in Chinatown.

Spanish missionaries founded San Francisco as a small mission town on the El Camino Real trail that linked their missions, and it barely grew under either Spanish or Mexican rule. In 1848, at almost exactly the moment that Mexico ceded California to the United States, people literally struck gold in the Sacramento River, marking the beginning of the Gold Rush.

In a single year, tens of thousands of Americans from back east as well as thousands of Irish refugees fleeing a famine in their homeland, swarmed through the city of San Francisco on their way to easy riches in the Sierra Nevadas. Most of them never found gold, but the City by the Bay had opportunities of its own to offer, and so many of the emigrants put down roots there during the California gold rush.

San Francisco’s population tripled in the 1860s, and then it tripled again before the end of the century, creating a human scrum of nearly half a million people living packed into slums and getting into fistfights over the inadequate common drinking troughs, which were the only source of “fresh” water for the poorest people in town.

In this crowded, unhygienic environment, it was inevitable that some Malthusian disaster would come along eventually. In fact, San Francisco suffered four disasters in a single generation, and the mass death set the stage for Colma to become California’s deadest city.

Four Horsemen, Ridden by Real Estate Developers

The State of CaliforniaBuildings burn in the aftermath of the Great Earthquake of 1906. Much of the city was destroyed by this disaster, though San Francisco quickly rebuilt.

Bubonic plague broke out in San Francisco in 1900. To respond to the crisis, city authorities took the probably-not-helpful step of outlawing new interments within city limits. Some plague victims were ferried, at considerable expense, across the Bay and buried in Oakland, others in Marin County to the north, and still others in families’ back yards — all in violation of city, county, and state law.

For religious reasons, cremation was uncommon at the time, and fewer people left their bodies to medical science than do today, and so the bodies kept piling up.

Then, almost as soon as the plague came under control, the city was hit with the infamous 1906 earthquake that struck on the morning of April 18th. San Francisco had been built without any particular attention to this then-unknown problem, and so most of the buildings collapsed after a minute or so of shaking.

The third disaster immediately followed the quake, as virtually the entire city caught fire and burned into ashes.

Twelve years later, just when San Francisco’s recovery was kicking in, the global Spanish Flu pandemic struck town.

Humans being what they are, people in San Francisco adapted to the troubles and kept rebuilding their town. Each new catastrophe brought new opportunities for the survivors to clear away old ramshackle slums and erect fresh buildings. Incredibly, even as death was stalking the city, people were still moving in and buying land to build a house.

Any normal city would have expanded outward in all directions, but San Francisco is, as its residents will tell you, not normal. The city occupies the northern tip of a peninsula (known as: “the Peninsula”), with seawater bounding it on three sides. Limited terrain and a rising population increase demand for space, and real estate started getting pricey.

Buying land for dead people to lie under didn’t seem like much of a plan, and in fact the city’s older graveyards were starting to look like increasingly desirable real estate. Meanwhile, those dead bodies weren’t going to bury themselves. City planners started looking south, to the howling wilderness of the Peninsula.

Cow Hollow Starts Filling Up

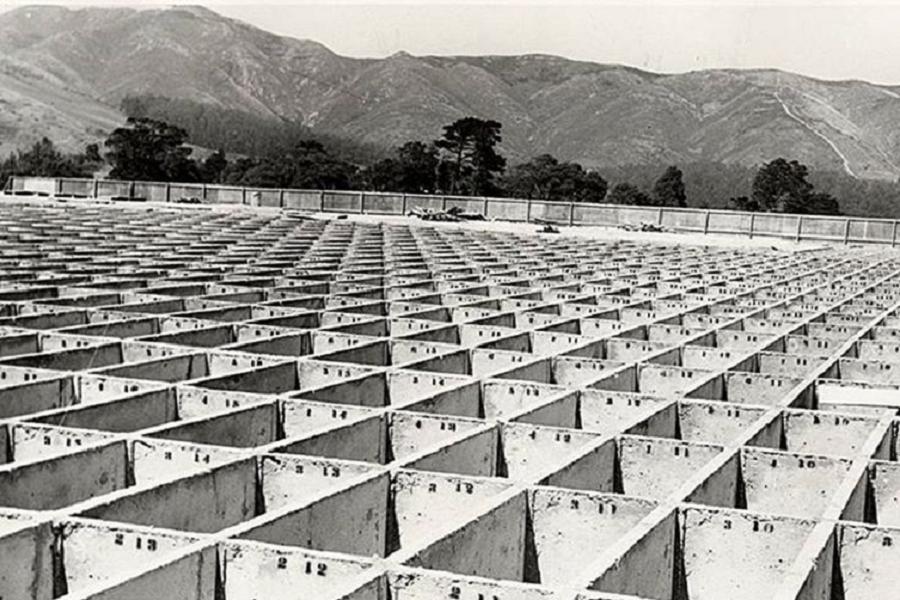

Wikimedia CommonsOpen sepulchers at Colma’s Holy Cross Cemetery await their new residents. Pat Brown and Joe DiMaggio are buried here.

South of San Francisco’s Mission District, adjacent to Daly City and not far from Pacifica, lies a two-square-mile patch that, in 1900, used to be known as Cow Hollow. About 150 to 300 people lived there in 1900 – nobody has the exact figure because the Census Bureau didn’t bother counting before 1920 – and the only business was a large nursery founded by a German immigrant, Henry von Kempf.

Cow Hollow was close to the city, underdeveloped, and populated mainly by trees; it was the perfect spot for new burials, and San Francisco’s funeral parlors started buying up land and digging holes all over it.

Another wrinkle appeared in 1912, when rumors started circulating in San Francisco that the graveyards in town were a source of contagion. What kind of contagion went unsaid, but residents came to believe that the dozen or so cemeteries left inside the city were leeching some kind of mysterious miasma into the air and making people sick.

That this rumor just happened to start circulating at a time when real estate developers were itching to buy up the last open spaces in the city, and at a time when some great political pressure had to be brought on the Board of Supervisors to dig up the graves and relocate the remains, is possibly a coincidence.

Whatever was going on, in 1912, the city began planning to permanently resettle tens of thousands of human remains to Colma.

Red Tape And Total War

Wikimedia CommonsSan Francisco’s population swelled during WWII, as war jobs brought people to the city. Many stayed on after the fighting was over, and they all needed a place to stay.

The relocations may have gotten the go-ahead in 1912, but red tape and bureaucratic sloth held up the project for years. In the early 1920s, Colma filed for incorporation as the City of Lawndale, but was rejected because another California city near Los Angeles had beaten them to it. The nameless town tried again in 1924, filing as Colma, and got approval to incorporate into San Mateo County.

At this time, the city still had fewer than 1,000 living residents, virtually all of whom worked in the funeral industry. Just as Detroit had cars and Pittsburgh had steel mills, Colma had graveyards and funeral parlors (though it seems the dead are less likely to up stakes and move to Mexico – many of Colma’s residents still work in the mortuary sciences). By 1930, a steady flow of recently deceased San Franciscans made their way into town to be buried.

Then, World War II radically changed the Bay Area. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, mid-Pacific naval bases were felt to be unsafe, and so much of the war effort shifted to mainland bases in Bremerton, Washington, and San Diego, California. Alameda was right across the Bay from San Francisco, and Port Chicago – the gargantuan ammunition dump that exploded in 1944 – was only a few miles farther north.

The war thus brought money, jobs, money, more jobs, shipping, jobs, and more money for jobs to the Bay, and a wave of formerly unemployed people came with it. San Francisco’s population began to grow again.

After the war, with millions of men demobilizing and looking for places to spend their VA loan money on a house, San Francisco and its surroundings started a housing boom that lasted to the end of the century. Real estate was more valuable than ever, and those wasteful city cemeteries had to go.

A Macabre Land Rush and Celebrity Grave Robbing

Wikimedia CommonsWorkers sift through the soil at San Francisco’s Odd Fellows Cemetery, today the site of the Angelo Rossi Playground and a public pool.

San Francisco’s mass exodus of the deceased began right after the war. All over town, cemeteries that had not accepted new residents in 40 years were dug up and torn down. Except for a religious cemetery at Mission Dolores Church, and a military site at the Presidio, all of the city’s yards were closed and dug up.

This was no small task – though no new bodies had been buried since 1900, San Francisco already had more than 150,000 graves by then, and by law every single one of them had to be certified empty before new structures could be started on the land. Developers were going to have to locate every plot in the city and dig for remains that may have been decaying for almost a century.

The economics of cemeteries made this task much harder than it had to be. Mortuaries charge a lot of money up front for what they do because the dead are notorious for not paying rent, and surviving relatives who care enough to pay for them eventually die themselves. When a grave occupant has no more living relatives who care to keep up the grave, it falls to the cemetery owner to do so, which the law requires them to do regardless of cost.

When new “customers” haven’t come through the door in over 40 years, even the youngest relatives of the residents have stopped paying their bills. With no money for upkeep, and even less for relocation, San Francisco’s 14 mortuary associations may have cut some corners with the disinterments, as in: they skipped a lot of them and probably didn’t look too hard for lost graves.

All of the headstones were ripped up, many to be ground up and used in construction, others just dumped in the Bay, and piles of dirt that the companies swore were human remains were solemnly trucked out to mass burial pits in Colma.

It’s likely that Wyatt Earp and his wife got this treatment, as did famous railroad-accident survivor Phineas Gage. Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico had been moved in 1934, with Levi Strauss and William Randolph Hearst also getting places in Colma.

“It’s Great to Be Alive In Colma”

Kai Schreiber/FlickrThe grave of Emperor Norton.

With land prices in the Bay Area nearly as high as they’ve ever been, and space still at a premium in the city, the flow of late San Franciscans to Colma has only increased. Abigail Folger is buried there, as are Pat Brown and Joe DiMaggio. Driven by the tech boom, the local economy has diversified somewhat.

At least some of the nearly 2,000 people in town work at jobs outside of funerary services, but the dead in Colma still take up 78 percent of the land area and are 99.9 percent of the residents. As the Bay Area’s population continues to increase, and San Francisco doesn’t get any bigger or cheaper, that ratio is likely to get even more lopsided until some canny real estate developer from the future starts whispering about miasmas again.

For more California nostalgia, be sure to check out San Francisco in the 1960s.