First proposed in 1977, Indigenous Peoples' Day aims to replace the increasingly controversial Columbus Day by honoring Native American history.

Erin Clark/The Boston Globe via Getty ImagesA demonstrator marches in Boston during an Indigenous Peoples’ Day rally on October 10, 2020.

For decades, the United States has celebrated Columbus Day on the second Monday in October. Businesses close, some employees have the day off work, and there’s a general acknowledgment of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the so-called “New World.” But there’s been a push in recent years to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

To Indigenous Peoples’ Day advocates, Columbus Day wrongly celebrates someone who caused great suffering for countless Native Americans. The Italian explorer, they point out, enslaved Indigenous people, brutally suppressed revolts, and brought devastating diseases to the Americas.

On the other side of the issue, however, is the complicated history of Columbus Day itself. Though it’s come to largely represent Christopher Columbus and his 15th-century journey to the New World, the holiday actually has its roots in Italian American persecution and pride.

Go inside the ongoing debate over whether Indigenous Peoples’ Day should replace Columbus Day — and see where the issue stands today.

The Surprising Origins Of Columbus Day

Bettmann/Getty ImagesItalian American women celebrate Columbus Day in 1942.

Columbus Day wasn’t enacted all at once. Rather, it took centuries for the government to declare the second Monday in October as a federal holiday.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, the idea to celebrate Christopher Columbus first arose more than 200 years ago. In 1792, the first documented celebration of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas took place in New York City, on the 300th anniversary of the navigator’s voyage.

One hundred years later, U.S. President Benjamin Harrison formally acknowledged the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival. As reported by NPR, Harrison called for a national observance of Columbus Day and linked Columbus’ legacy with American history as a whole.

“On that day let the people, so far as possible, cease from toil and devote themselves to such exercises as may best express honor to the discoverer and their appreciation of the great achievements of the four completed centuries of American life,” Harrison proclaimed.

But then, something unexpected happened. Though Harrison had made no mention of Christopher Columbus’ Italian heritage, “Columbus Day” was quickly claimed by Italian Americans. At the time, Italian Americans — many of whom had arrived during an influx of immigration starting in the 1880s — faced discrimination and violence from their new countrymen.

They saw the celebration of Christopher Columbus as a way to be accepted by the United States — and started to push for Columbus Day to become a national holiday. Fourteen years after Harrison’s proclamation, in 1906, Italian Americans in Colorado successfully convinced that state to officially observe Columbus Day. And before long, many other states followed.

It took decades, but Columbus Day eventually became a federal holiday. As the Smithsonian explains, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared the first national observance of Columbus Day in 1934 after pressure from the Knights of Columbus (a Catholic organization) and Italian Americans. Columbus Day then became a federal holiday in 1937. And in 1972, President Richard Nixon declared that it would fall on the second Monday in October.

But even though Italian Americans had pushed for Columbus Day as a way to find acceptance in American society, the idea of celebrating Christopher Columbus didn’t sit well with many Indigenous people in the country.

The Emergence Of Indigenous Peoples’ Day

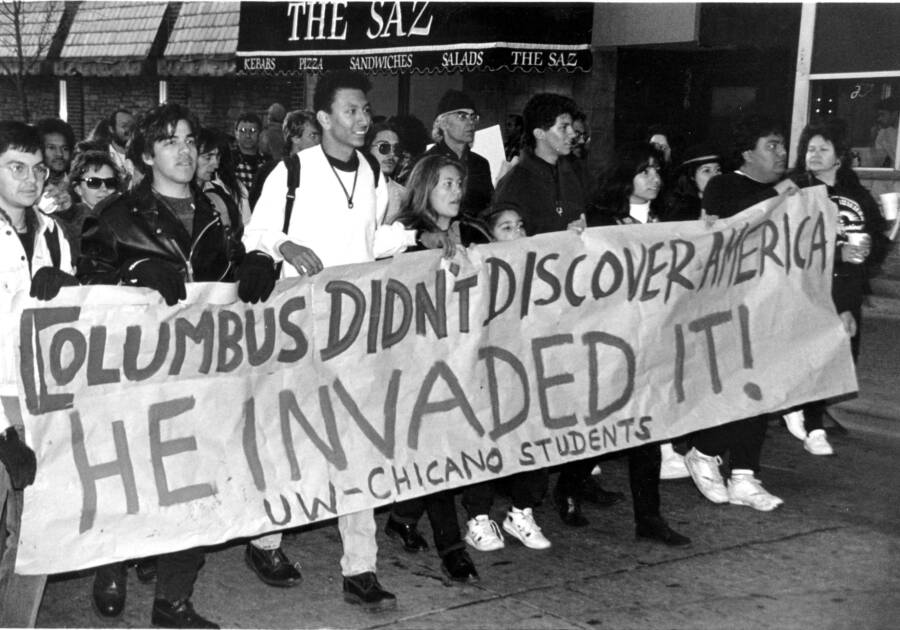

UW Archives Chicano students at the University of Wisconsin protest the celebration of Columbus Day in 1992.

For many Indigenous people living in the United States, Christopher Columbus wasn’t worth celebrating. After all, as History notes, his arrival in the Americas had brought death and disease to their ancestors. Plus, Columbus hadn’t really “discovered” a new world — they were already there.

National Geographic reports that the pushback against Columbus Day grew starting in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1970, “Red Power” activists defaced a Christopher Columbus statue in New York on Columbus Day. And in 1977, according to the Smithsonian, delegates at the United Nations International Conference on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations in the Americas proposed replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

This idea gained prominence as time went on. In 1990, ahead of the 100th anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre — during which U.S. soldiers slaughtered 300 Lakotas — South Dakota declared that it would no longer celebrate Columbus Day. Instead, it would observe Native American Day.

Two years later, during the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas in 1992, Indigenous activists spoke out against Columbus Day again. In response, the city of Berkeley, California, replaced it with a holiday called “The Day of Solidarity with Indigenous People.”

Since then, other cities and states have decided to stop celebrating Columbus Day and to observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead.

Will Indigenous Peoples’ Day Eventually Replace Columbus Day?

David McNew/Getty ImagesSupporters of Indigenous Peoples’ Day watch a local Tongva tribal elder speak in California in 2017, shortly after the city of Los Angeles approved Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a replacement for Columbus Day.

According to The Conversation, over a dozen states and the District of Columbia now recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Some of these states include New Mexico, Oklahoma, Virginia, North Carolina, and Vermont.

Other states honor their Indigenous history with another holiday, like Hawaii with their Discoverers’ Day, which pays tribute to the Polynesian navigators who located the islands. And over 100 cities celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day (or another Native American holiday). What’s more, some of these city and state governments have dropped Columbus Day altogether.

In 2021, President Joe Biden made history by becoming the first U.S. president to officially recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day. In a proclamation released by the White House, Biden declared: “On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we honor America’s first inhabitants and the Tribal Nations that continue to thrive today. I encourage everyone to celebrate and recognize the many Indigenous communities and cultures that make up our great country.”

Indeed, many Native American activists hope that Indigenous Peoples’ Day will be seen as more than a counter-celebration. They want people to take the time to learn about Native American history and culture.

While there are no specific rules as to how someone should mark the holiday, many tribal leaders suggest reflecting on Indigenous history in the United States and learning about the diversity of Native American people in the country. One easy way to start might be learning which Indigenous land you’re currently living on — and researching more about that tribal group.

But despite the groundswell of support for Indigenous Peoples’ Day, not everyone is happy about it. Some have pointed out that Columbus Day, at its roots, is about celebrating Italian American heritage and history.

“Italians are intensely offended,” Lisa Marchese of Seattle, Washington, said of the city’s push to cast aside Columbus Day for Indigenous Peoples’ Day, according to the Washington Post. “For decades, Italian Americans celebrated not the man, but the symbol of Columbus Day. That symbol means we honor the legacy of our ancestors who immigrated to Seattle, overcame poverty, a language barrier, and above all, discrimination.”

For now, Columbus Day remains a federal holiday in the United States. But supporters of Indigenous Peoples’ Day are pleased with the growing acceptance of their holiday — and see it as an important acknowledgment of the suffering of their ancestors at the hands of people like Columbus.

Reyn Leno, the chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde in Oregon, told The Oregonian that there is still more work to be done, but the holiday is a step in the right direction. “You can’t erase history and culture with a piece of paper and pencil,” he said. “But you can do things like this.”

After learning about Indigenous Peoples’ Day, go inside the complicated history of who discovered America. Then, read about Leif Erikson, the Viking explorer who was likely the first European to set foot in the Americas.