A Norse explorer from Iceland, Leif Erikson is believed to be the first European to reach North America around 1000 A.D. This is his story.

In approximately 1000 C.E., Norse explorer Leif Erikson established a settlement he called Vinland in what’s believed to be present-day Newfoundland. This would make Erikson the first European to set foot in North America — some 500 years before Christopher Columbus, the man who supposedly “discovered” America.

Columbus has become an increasingly controversial figure in recent years. Discussions of his journey to the New World must reckon with the brutal slaughter and mistreatment of Native Americans that happened in its wake.

Wikimedia CommonsNow honored with Leif Erikson Day on October 9, Norse explorer Leif Erikson is widely believed to be the first European seafarer to reach the shores of North America.

What’s more, it’s become more widely known that Columbus never actually set foot in mainland North America in the first place. However, the evidence indeed suggests that Leif Erikson did.

According to both historical accounts and archaeological evidence uncovered in the 1960s, many scholars now believe that Leif Erikson reached North America. But who was Leif Erikson and did he truly “discover” North America 500 years before Columbus?

Who Was Norse Explorer Leif Erikson?

Leif Erikson (also spelled Leif Eriksson, Leif Ericson, or Leifr Eiríksson in Old Norse) was likely born in Iceland around 970-980 A.D. He was nicknamed “Leif the Lucky” by his father, the famous explorer Erik the Red, who established the first Viking colony in Greenland around 985 A.D. — after he was banished from Iceland for murder.

In Greenland, a young Erikson met wealthy farmers and chieftains who were pioneers in this new land. Perhaps that’s how he decided to sail the Atlantic one summer. The truth is, historians have not confirmed this — or much of Erikson’s life — for certain.

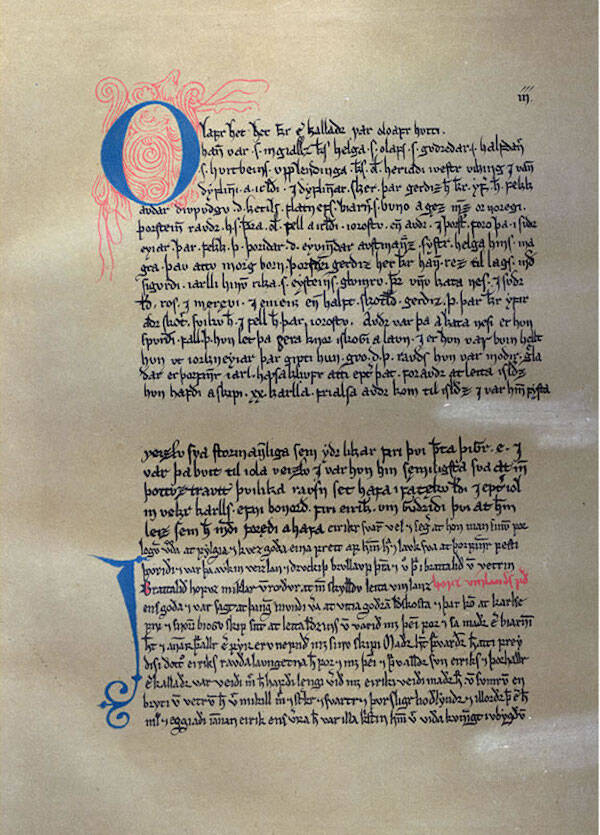

Indeed, understanding the history of the Vikings as a whole is not an easy task. Most of the information that historians have gathered on Leif Erikson stems from the 13th-century Vinland Sagas, a collection of tales that tell the story of Erikson’s heritage, beginning with his father, Erik the Red, in the eponymous collection Erik the Red’s Saga. This is followed by The Saga of the Greenlanders. However, neither document is by any means entirely factual.

Wikimedia CommonsHvalsey Church in Greenland. One of the best-preserved remnants from Norse settlements on the island.

These half-legends are semi-historical accounts and they do corroborate the assertion that Leif Erikson landed in America hundreds of years before Columbus did. But that doesn’t mean these tales are totally reliable sources.

After all, these accounts were written down more than 200 years after the events happened. The documents do suggest, however, that these events did occur. They were probably mentioned in stories that were passed down orally, and they most likely referred to real people and actual incidents.

Perhaps the strongest evidence is that the archaeological remains of a Norse settlement were unearthed at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland in the 1960s. These remnants were right where the stories said the Vikings had settled.

But long before this evidence came to light, the sagas of Leif Erikson’s journeys were the sole documents of his adventures.

The Saga Of The Greenlanders And Erikson’s Journey To North America

There are two different accounts of Leif Erikson’s arrival in North America. One account described in Erik the Red’s Saga asserts that Erikson was blown off course in the Atlantic while sailing back home from Norway and that he accidentally landed on American shores.

The Saga of the Greenlanders, meanwhile, explains how the Viking’s voyage to North America was no mistake. As the story goes, Erikson had heard of the unexplored continent from an Icelandic trader named Bjarni Herjólfsson, who stumbled upon it a decade earlier while miscalculating a voyage to Greenland.

However, Herjólfsson never disembarked, which would give Erikson the hypothetical chance to be the first European to reach North America. In The Saga of the Greenlanders account, Erikson bought Herjólfsson’s ship, organized a 35-person crew, and successfully retraced the trader’s route.

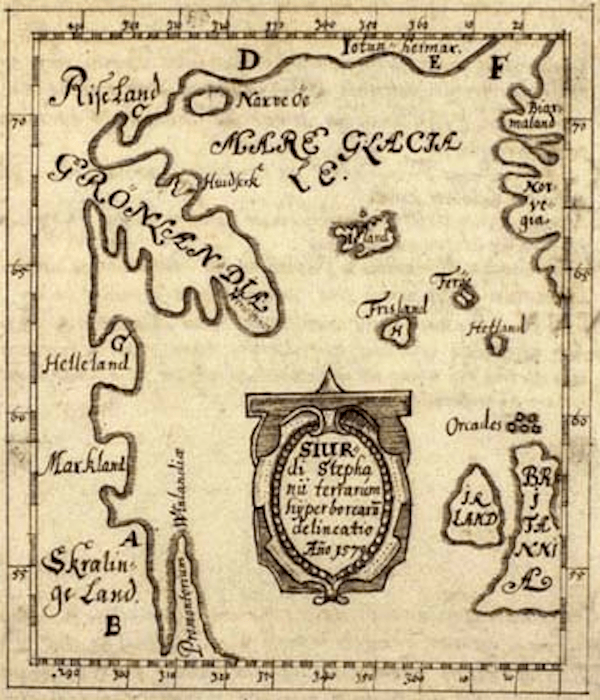

Wikimedia CommonsThis 1590 Skaholt Map shows the Latinized Norse place names in North America. These include the Land of the Risi (a mythical place), Greenland, Helluland (Baffin Island), Markland (on the Labrador Peninsula), the Land of the Skrælingjar (unknown), and Vinland in Newfoundland.

Upon crossing the Atlantic, the crew encountered a piece of land covered in stone that they aptly named Helluland or “Stone-slab Land,” which was likely Labrador or Baffin Island.

They then landed in a wooded area that they named Markland or “Forest Land,” which was likely Labrador, and finally set up base at Leifsbúdir or “Leif’s Booths,” which was probably somewhere on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

The band of Vikings was said to have ventured south where they encountered an exciting place full of timber and grapes. Here they named the land “Vinland,” or Wine Land. Leif Erikson and his men reportedly spent the whole winter there, luxuriating in the weather, exploring the meadows, and feasting on salmon and grapes.

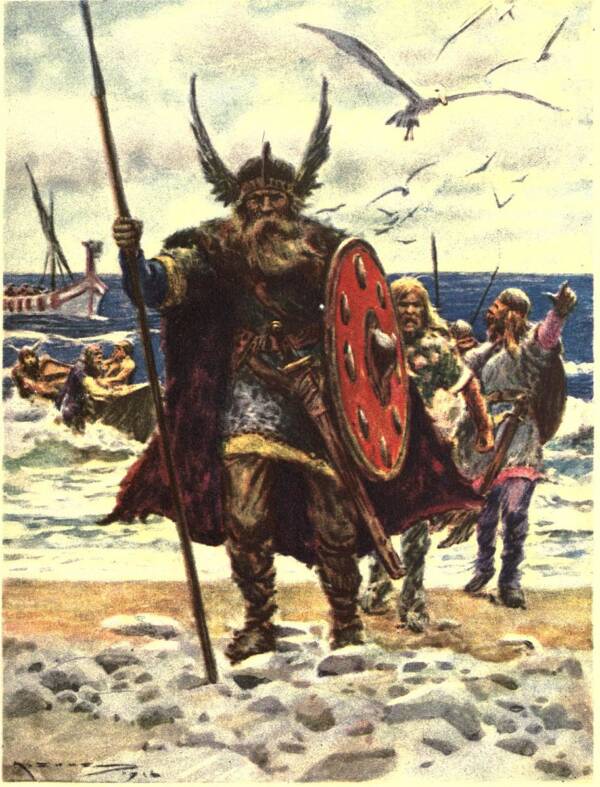

Wikimedia CommonsJens Erik Carl Rasmussen’s 19th-century painting, “Summer In The Greenland Coast Circa Year 1000,” depicts how Leif Erikson and his men would’ve lived during their time in North America.

The saga ends as the Vikings return to Greenland — with timber and grapes in tow.

Erikson never returned to the New World, according to The Saga of the Greenlanders. Perhaps this was because Erikson’s brother Thorvald was later slain during another Viking expedition to Vinland after a skirmish broke out between the Norsemen and Indigenous people.

Little is known for sure about Leif Erikson’s later life, although the last mentions of him alive in writing date to 1019 A.D., with his status of chieftain passing to his son in 1025 A.D.

Meanwhile, Erik the Red’s Saga recounts Leif Erikson’s purported discovery in a different way.

When Leif Erikson Discovered America, According To Erik The Red’s Saga And The Archaeological Evidence

This saga contradicts much of The Saga of the Greenlanders, most thinly by naming Leifsbúdir as Straumfjordr or the “Ford of Currents” instead. It’s possible this is because Erik the Red’s Saga was purposefully written to minimize Leif Erikson’s contributions in favor of his sister-in-law, Gudrid, and her husband Karlsefni.

The pair are presented throughout this saga as spearheading the discovery of the New World on a singular voyage to Vinland. Some attribute this alternate account to a 13th-century movement that prioritized canonizing Bishop Björn Gilsson, who was a direct descendant of the couple.

Wikimedia CommonsA page from the 13th-century manuscript of Erik The Red’s Saga. It differs substantially from The Saga of of the Greenlanders.

The couple is written to have established a temporary hub, home to between 70 and 90 people, at Straumfjordr. It’s believed that this base camp was used to deploy further expeditions to other areas in order to collect timber, grapes, furs, and any other valuable or functional materials to bring home to Greenland.

Regardless of whether the hub was named Straumfjordr or Leifsbúdir, it was nonetheless believed to have been situated at the northern tip of Newfoundland, where archaeological remnants of a Norse settlement were discovered in the 1960s by Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad, his wife, and a team of archaeologists. The settlement included eight buildings, such as huts and chieftains’ halls.

According to Ancient Origins, another discovery made at this site revealed a small chapel dedicated to Leif Erikson’s mother, Thjodhild. It was large enough to hold 20 to 30 people.

During the excavation process, 144 skeletons were unearthed as well. Most of the remains indicated these were tall and strong people, which was further evidence that they might’ve been Scandinavian.

Wikimedia CommonsHenrietta Elizabeth Marshall’s 1876 painting of the Vikings’ landing in North America.

According to the BBC, the Viking settlement did correspond thoroughly to the descriptions of Vinland that Erikson handed down.

These discoveries serve as strong scientific evidence that these tales were both rooted in at least some semblance of historical accuracy. Today, the settlement is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Despite this evidence, Christopher Columbus has been firmly established in mainstream history as the figurehead of European discovery and the consequent colonization of North America. The moment when Leif Erikson discovered America, on the other hand, has gone overshadowed.

But how did this happen?

Christopher Columbus Day Vs. Leif Erikson Day

Wikimedia Commons“Leif, The Discoverer” by Anne Whitney. 1887.

By 1907, Colorado became the first state to officially recognize Columbus Day. A few years later, 15 states followed suit. In 1971, it became a federal holiday.

The anniversary of when Leif Erikson discovered America is commemorated with a niche holiday every October 9th. This was made a national day of observance in 1954. Because of the highly contentious nature of Columbus Day, the push to celebrate Leif Erikson Day in its stead has in some ways become an alternative for those who feel too queasy to celebrate Columbus.

However, it’s worth noting that the Vikings may not have had a good relationship with the Indigenous people they encountered — especially considering the story of Erikson’s brother being slain in a battle against them. It’s also worth noting that the push to celebrate Erikson over Columbus has unsavory roots in anti-Catholic and anti-Italian sentiment.

Wikimedia CommonsA recreation of a traditional Norse longhouse in L’Anse Aux Meadows. Newfoundland, Canada. 2010.

By the time Italian Americans celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery in 1892, a sentiment of anti-immigration and paranoia surrounding the Catholic Church had overcome America.

National University of Ireland history professor and author of Discovering Viking America, JoAnne Mancini, said that Americans “who were not Catholic were really paranoid about the Catholic Church” in the 19th century. Conspiracy theories that the Vatican may have actively suppressed Erikson’s accomplishments grew as a result.

Therefore, “the idea that there might be a story where the first Europeans to America are not Southern Europeans” became increasingly popular during this time as Scandinavian immigrants pushed for their own narrative.

Wikimedia CommonsLeif Erikson may not have been commemorated with a federal holiday, but he did get his own stamp in 1968.

But the narrative of Columbus’ discovery nonetheless managed to overtake Leif Erikson’s, Mancini believes, because of a longstanding tradition of Italian lobbyists and the notion that Columbus may have inspired more European migration to America than Erikson had.

“If you think about the subsequent history of the European conquest of America, that comes from Columbus; it doesn’t come from Leif Erikson,” Mancini elaborated. “It’s interesting that the Vikings were able to cross the Atlantic, but… Columbus had more of an impact in the long run.”

Wikimedia CommonsChristian Krohg’s 19th-century painting of the moment when Leif Erikson discovered North America.

As it stands, this duel of nationalities and cultural pride has virtually ceased in favor of a more pressing battle — whether or not to eradicate a holiday that celebrates colonization in favor of one that recognizes the plight of Indigenous Americans.

As such, some states have chosen to rename Columbus Day to celebrate Indigenous people instead, including South Dakota, Minnesota, Vermont, North Carolina, and Oregon. New Mexico recently passed a law to officially recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day over Columbus Day. And Hawaii observes Discoverers’ Day — in honor of its Polynesian founders.

As the ethnic makeup of American culture continues to evolve, so too does the discourse around how to remember the country’s past. But regardless of the politics and the changing times, the fact remains that, as far as archaeologists and historians are concerned, Leif Erikson was likely the first European to ever reach North America, securing his place in the history books.

After learning about when Leif Erikson discovered America, read about shieldmaidens, the Viking warrior women as fierce as their male counterparts. Then, learn some of the most interesting facts about Vikings.