The AIDS Epidemic Of The 1980s

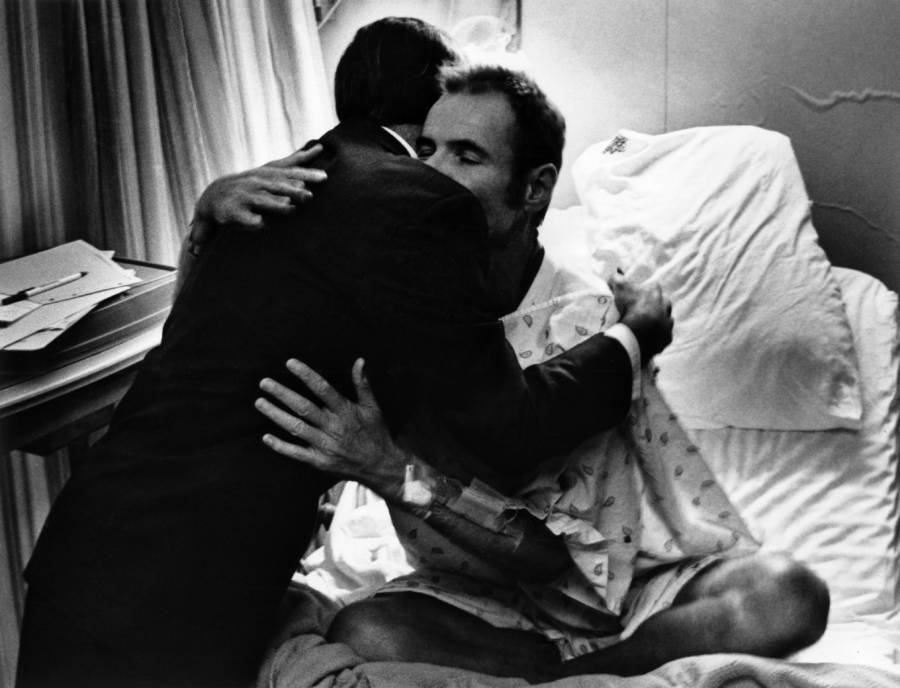

Bettmann/Getty ImagesWashington, D.C., doctor Richard DiGioia hugging his patient, Tom Kane.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) arrived without warning nor explanation in 1981. Doctors in New York City and California were suddenly finding inexplicably enlarged lymph nodes, rare types of pneumonia, and odd cancers among gay men, intravenous drug users, and recipients of blood transfusions.

The world didn’t know it yet, but an invisible killer had arrived to ravage cities across the country. The condition was only given a name by the CDC in 1982: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

Experts believed it had crossed over to humans from chimpanzees in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as early as 1920. It spread silently for decades before a strong type of pneumonia and rare cancer known as Kaposi’s Sarcoma emerged among gay Americans in 1981 — when 121 of the 270 known victims died.

Los Angeles Public LibraryThousands of people gather for a candlelight vigil in honor of AIDS victims in Los Angeles, California, on May 30, 1987.

It became rapidly clear that about half of those infected with HIV in the United States would die of an AIDS-related condition within two years of infection. The deadly condition began stigmatizing the already marginalized — gay men, people addicted to drugs, and the unhoused.

At the height of its spread in 1995, AIDS killed 50,000 per year. Those figures boiled down to 4,500 people dying every of the condition every single month, or around 150 people per day. Researchers were desperate to identify the virus itself.

Fortunately, the federal government began screening the U.S. blood supply and licensed an HIV antibody test by 1985 — the same year that the American Foundation for AIDS Research was founded. While early remedies were lacking, antiretroviral therapies that saw infections plummet emerged by the late 1990s.

Despite sex education and HIV prevention measures being funded and promoted ever since, up to 15,000 AIDS-related deaths still occur each year. In total, 700,000 Americans have died of AIDS since 1981.