Deadliest Days In U.S. History: The 1918 Flu Pandemic

Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty ImagesSt. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps workers on duty.

As World War I raged across Europe, the United States was embroiled in a battle of its own at home. It was no army of invaders nor a domestic threat that the country was facing, but an invisible killer with a mortality rate the world hadn’t suffered since the Black Plague.

While the war in Europe accounted for 20 million deaths from 1914 to 1918, the Spanish Flu claimed at least 50 million lives across the globe. The H1N1 influenza strain affected one-fourth of the world population as it swept from tropical islands in the Pacific to the isolated towns in the Arctic.

Although experts remain uncertain how or where the deadly virus first emerged, it has since become clear that World War I furthered its spread and bolstered its mortality rate. And the worst of it hit the U.S. in October 1918, bringing the country to a standstill.

That month, the virus killed 195,000 Americans — an average of more than 6,000 people per day. According to experts, any one of October’s 31 days that year is more than likely the deadliest day in American history.

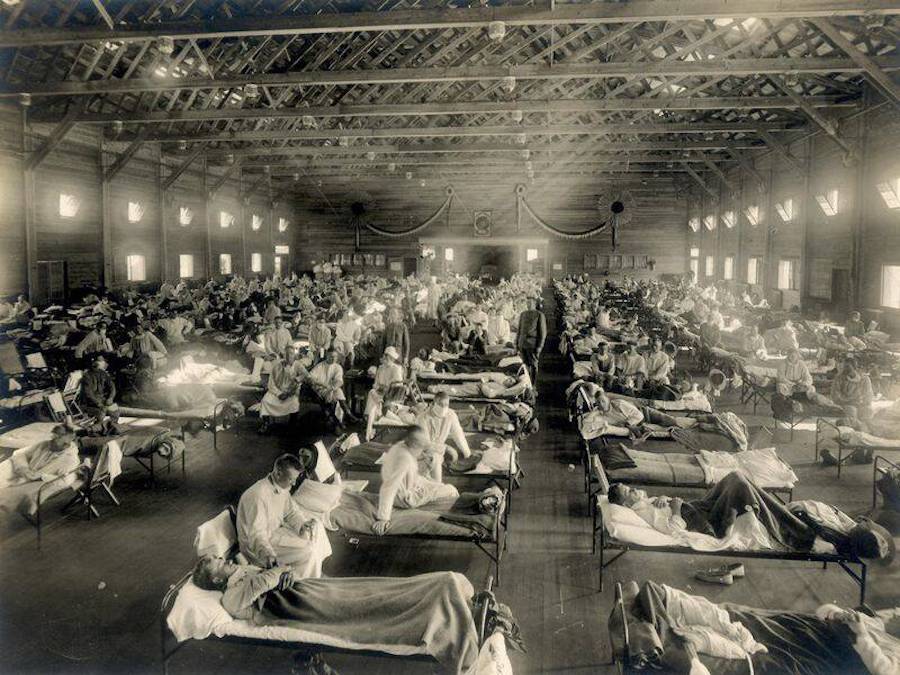

Wikimedia CommonsSoldiers with the Spanish flu lie in beds at Kansas’ Camp Funston.

Cities were utterly devastated, with public places such as churches, schools, bars, and theaters shuttered. San Francisco residents who refused to wear masks were fined or sent to jail, while New York City Health Commissioner Royal Copeland kept public venues open. Most impacted of all was the city of Philadelphia.

Public Health Director Wilmer Krusen decided not to cancel a parade that promoted the sale of government war bonds. Around 200,000 people attended the gathering, leading the city’s hospitals to be inundated three days later. That October, more than 11,000 Philadelphians died — with the deadliest day killing 759 people.

To the relief of citizens across the U.S., the Spanish Flu seemed to vanish as unexpectedly as it had arrived. While cases skyrocketed once more after citizens celebrated the armistice of World War 1 on Nov. 11, the flu abated in 1920 — after 675,000 Americans in total had died.