In stark contrast to the Hitler Youth, the Edelweiss Pirates resisted Nazism in any way they could at a time when doing so was a criminal offense.

Despite leaving behind little information on their exploits, a group of German teenagers known as the Edelweiss Pirates played an important role in Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

Much like the tenacious edelweiss flower clinging to the crags of Austria’s Alps that the group was named after, these young Germans resisted Nazi indoctrination.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesA group of Edelweiss Pirates in Nazi Germany. The Pirates emerged in western Germany out of the German Youth Movement of the late 1930s in response to the strict regimentation of the Hitler Youth. 1938.

They saw themselves as the opposite of the infamous Hitler Youth, rejecting their paramilitary structure, Nazi ideology, and gender segregation.

Hailing from working-class backgrounds, the Edelweiss Pirates resisted Nazism in any way they could — all before their 18th birthdays.

The Hitler Youth

According to Sally Rogow of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Center, the Edelweiss Pirates was “one of the largest youth groups who refused to participate in Nazi youth activities.”

To understand the Pirates, we first have to understand what they were up against. Formed in 1922 as the Youth League of the Nazi Party, it was renamed the Hitlerjugend, or Hitler Youth, in 1926 and was comprised of German boys aged 14 to 18. Four years later, the Nazis established an equivalent organization for teenage girls called the Bund deutscher Mädel, or League of German Girls.

At its height, the Hitler Youth had eight million members, making it the largest youth organization in the world. Although the Youth initially focused on standard activities such as camping, sports, and games, it increasingly became militarized, training its young boys for armed combat.

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty ImagesHitler Youth members burn books at an unspecified location. 1938.

It soon became clear that the goal of the Hitler Youth was to indoctrinate Germany’s young people with Hitler’s aggressive, Nazi worldview.

As Adolf Hitler himself described it in 1938:

“These boys and girls enter our organizations [at] 10 years of age, and often for the first time get a little fresh air; after four years of the Young Folk they go on to the Hitler Youth, where we have them for another four years….And even if they are still not complete National Socialists, they go to Labor Service and are smoothed out there for another six, seven months….And whatever class consciousness or social status might still be left…the Wehrmacht [German armed forces] will take care of that.”

Who Were The Edelweiss Pirates?

The Edelweiss Pirates, or Edelweißpiraten, was a collective of local anti-Nazi resistance groups founded largely in western Germany. Aged 14 to 17, these teenagers rejected the Hitler Youth’s and League of German Girls’ dark aspects: restrictions on teenagers’ fun and freedom of thought, and training kids for military service.

Many of them left school at age 14 — which was common for working-class teens at the time — in order to sever ties with the Nazis, and some dropped out of the Youth. Membership was compulsory beginning in 1936, and in 1939 — the same year World War II began — non-membership became a punishable offense.

But the Edelweiss Pirates had only a few years of freedom since they were typically forced to join the army when they turned 18.

The Edelweiss, a flower growing in the Alps, became a symbol of resistance for the Pirates.

Everything the Hitler Youth stood for was everything the Edelweiss Pirates stood against. The Youth wore their hair high and tight and closely shorn, while the Pirates wore theirs long and free. The Hitler Youth were segregated by gender, whereas Pirates were coed and some engaged in sexual experimentation. The differences extended further.

While the Youth wore standardized uniforms and listened to Nazi propaganda music, the Edelweiss Pirates wore checkered shirts and lederhosen and played music composed by Jewish musicians and other non-state-sanctioned songs.

The Edelweiss Pirates’ Antics

More than just a proto-hippie fantasy, these anti-fascists were flesh and blood teens. Many of their adventures were kept secret, so information on them can be hard to come by.

Much of the Edelweiss Pirates’ time was spent in youthful rebellion to Nazism. One former Pirate recalled pouring sugar in the gas tank of Nazi officers’ cars, hurling bricks through the windows of munitions factories, and graffiti-ing messages like “Down with Hitler” and “Down with Nazi Brutality.”

They listened to the verboten BBC world service on the radio. When the Allies dropped anti-Nazi propaganda from their airplanes, the Pirates made sure to gather the leaflets before the Nazis snatched them up; they would organize leaflet drops in nearby towns so the local police wouldn’t recognize them.

Meanwhile, their more daring activities included shielding German deserters and escaped concentration and labor camp prisoners, and supplying adult resistance groups with explosives.

Anything that could weaken the Nazis’ morale was fair game to the youthful Pirates. And many of them faced brutal punishment, from forced head-shaving to torturous prison sentences to public hangings.

Indeed, the Edelweiss Pirates were real people, with beating hearts, and parents — and names.

Walter Mayer And Barthel Schink

Walter Mayer, from Düsseldorf, recalled a meeting with fellow Pirates at a pool hall. A member would ask, “‘What are we going to do next?’ and maybe one would say, ‘You know the Hitler Youths? They all store their equipment at such-and-such a place. Let’s make it disappear.'”

The raids began small and then snowballed.

“We started maybe by deflating the tires. Then we made the whole bicycle disappear.”

Ullstein Bild/Getty ImagesBartholomäus “Barthel” Schink, an Edelweiss Pirate, was hanged by the Nazis when he was only 16.

Mayer’s father was deeply anti-Nazi, and while Mayer did join the Hitler Youth, he fought against them by hiding Jewish friends in the basement and working with the Edelweiss Pirates.

At one point, he was found stealing shoes and was arrested by Nazi authorities. Mayer remembered the prosecutor pushed for the death penalty, but the judge, considering the boy’s athletic achievements, sentenced him to one to four years in prison.

Mayer was lucky. Most infamously, the Gestapo publicly hanged 13 people, including six of Cologne’s Edelweiss Pirates, including 16-year-old Barthel Schink, on the morning of Nov. 10, 1944. The group was accused of planning an attack on the local Gestapo headquarters. None of them had been tried.

Now, the street near where they were hanged is named after Schink.

Gertrud Koch

Gertrud Koch, born in Cologne in 1924, refused to join the League of German Girls. Instead, she co-founded Cologne’s Edelweiss Pirates chapter.

She later remembered how her family hid a Jewish musician in their garden from 1938 to 1939. “We took him food there for about a year and a half,” she said.

Later, she led the Pirates’ leaflet drop from the top of Cologne’s train station. For that she was jailed for nine months at Brauweiler, where the Gestapo beat her and once threw her down the stairs, breaking her arm.

Her father, a communist, died in the Esterwegen concentration camp in northwest Germany.

Koch had once dreamed of becoming a Montessori school teacher. Now her only wish was to make it out of the war alive. She and her mother fled to the mountains to hide for the last two years of World War II.

Until her final days in 2016, she went by her Pirate codename “Mucki.”

Fritz Theilen

Wikimedia CommonsHeinrich Himmler, center, was a leading member of the Nazi Party and an architect of some of the Holocaust’s worst atrocities.

Fritz Theilen was another Pirate who faced the corrupt Nazi court system. He apprenticed at Ford Motor Company plant in Cologne when he left school at 14 and became disillusioned by the slave labor of the outfit.

He donned his Pirate badge — a metal pin depicting an edelweiss flower — in 1942, and was picked up by the Nazi secret police in 1943. Brutalized and released after a few weeks, Theilen had many more run-ins with the Nazis. He even escaped from a sub-facility of the dreaded Dachau concentration camp in 1944.

When the war ended, he wished to return to Ford, but the management wouldn’t let him. Nazism was still alive and well in many circles; to them, Theilen wasn’t a hero, but an agitator and common criminal.

“I never thought I would have to justify myself,” he said.

He only got hired back with the help of the British forces occupying western Germany.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAdolf Hitler smiles while uniformed youths salute him in Erfurt, Germany, 1933.

Hans And Sophie Scholl

The Edelweiss Pirates were one of the biggest youth groups to resist Nazi control, but they weren’t the only one. Another was the White Rose nonviolent resistance group, which counted German siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl as members.

The Scholls’ father detested the Nazi regime. He told his children: “What I want most of all is that you live in uprightness and freedom of spirit, no matter how difficult that proves to be.”

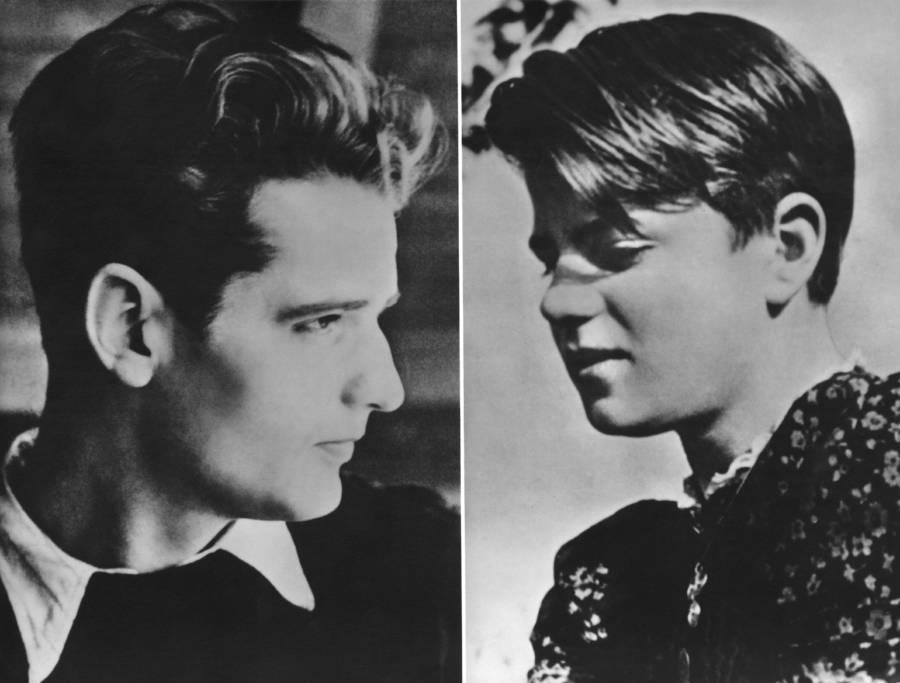

Authenticated News/Archive Photos/Getty ImagesHans Scholl (left) and his sister, Sophie Scholl. Circa 1940.

The Scholl siblings and other members of the White Rose took his message to heart, leaving the Nazi party and working against it.

Moved to resist the Nazis’ mass murders on the Eastern Front on moral, ethical, and religious grounds, the group printed leaflets with messages like: “the German name will be forever defamed if German youth does not finally arise, avenge, and atone, if he does not shatter his tormentor and raise up a new intellectual Europe.”

The Scholls and Christoph Probst were sentenced to death by beheading. Even though Sophie was offered a lighter sentence if she denied her work with the White Rose, she chose to die with her brother for their beliefs.

They were beheaded by Nazi forces on Feb. 22, 1943. To this day, the Scholl siblings and the White Rose, or Weiße Rose remain a symbol of German resistance to Hitler’s Nazi regime.

The Edelweiss Pirates’ Legacy

Wikimedia CommonsSurviving Edelweiss Pirates in Cologne, Germany in 2005, after finally being recognized as resistance fighters.

While the White Roses — a group composed of university students and professors — have been celebrated for their resistance since the end of the war, it took 60 years for the Edelweiss Pirates to be officially recognized as full-fledged resistance fighters instead of criminals.

“We were from the working classes. That is the main reason why we have only now been recognized,” Koch declared.

“After the war there were no judges in Germany so the old Nazi judges were used and they upheld the criminalization of what we did and who we were.”

Today, the Edelweiss Pirates’ bravery, righteousness, and resistance to Nazism at a time when much of Germany willfully followed Hitler’s authoritarian regime is rightfully celebrated.

After reading about the teenaged Edelweiss Pirates’ anti-Nazi resistance, learn about Meyer Lansky’s Nazi-punching gang and Che Guevara’s incredible life fighting imperialism in Latin America.