American cryptologist Elizebeth Smith Friedman cracked codes during World War I, Prohibition, and World War II — but her accomplishments weren’t revealed until after her death.

For decades, the United States had a secret weapon. During World War I, World War II, and Prohibition, the country frequently turned to a talented codebreaker named Elizebeth Smith Friedman to crack enemy ciphers and rumrunners’ secret codes alike.

Gifted with the ability to notice patterns that others missed, Friedman became one of the first American codebreakers during World War I. In the subsequent decade, she and her clerk cracked 12,000 encryptions sent by bootleggers during Prohibition. And during World War II, Friedman’s codebreaking skills helped avert a Nazi plot to start coups in South America.

Yet for all her accomplishments, Friedman’s work often went unnoticed. Men like J. Edgar Hoover frequently took credit, and Friedman herself promised to never speak of her work during her lifetime.

But in 2008, declassified files revealed the truth — that Elizebeth Friedman, the “Mother of Cryptology,” had played a crucial role as a codebreaker during some of the nation’s most perilous moments.

How A Love Of Shakespeare Led To Codebreaking

Born on Aug. 26, 1892, Elizebeth Smith Friedman — so named by her mother so that she would never be called “Eliza” — had a love of words from the beginning. According to Time she enjoyed reading and writing from a young age, and Smithsonian Magazine reports that she insisted on attending college as an English Literature major against her father’s wishes.

Settling in Chicago, Friedman had a chance encounter at the Newberry Library that changed her life. While visiting the library to examine a 1623 original edition of Shakespeare’s First Folios, a librarian recommended she contact George Fabyan, a millionaire hoping to use codebreaking to prove that Shakespeare’s works had actually been written by Sir Francis Bacon.

Working for Fabyan at Riverbank Laboratories, Friedman learned about codebreaking — and met her husband, William. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, they were drawn together by a disdain for one of their superiors, who they believed saw patterns where none existed, and their shared love for cracking codes.

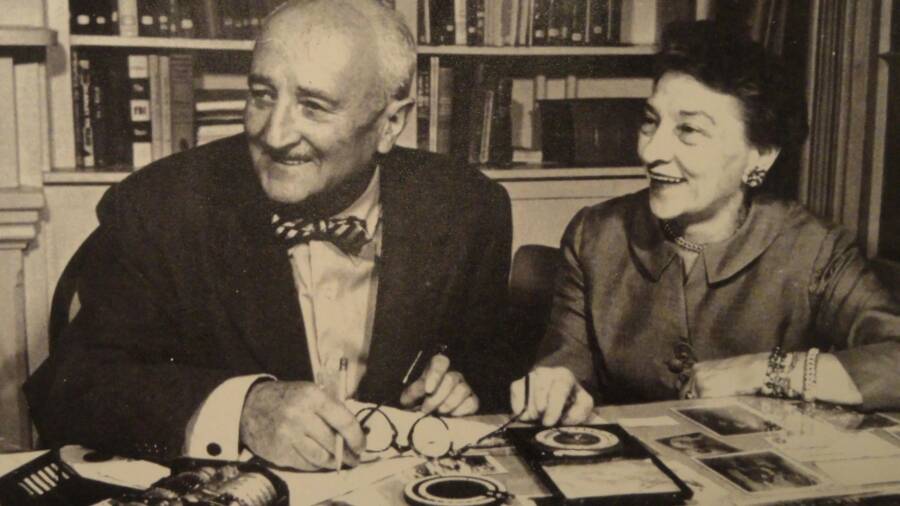

Public DomainWilliam Friedman And Elizebeth Smith Friedman in 1917.

When World War I broke out, Smithsonian Magazine reports, Fabyan volunteered his team of codebreakers to the War Department to help decipher enemy messages. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, there were just a handful of codebreakers in the U.S. at the time, and Friedman and her new husband were two of them.

“So little was known in this country of codes and ciphers when the United States entered World War I, that we ourselves had to be the learners, the workers and the teachers all at one and the same time,” Friedman noted in an unpublished memoir reported by Smithsonian Magazine.

As the war raged, Elizebeth Smith Friedman and her husband got to work.

Elizebeth Smith Friedman’s Early Codebreaking Accomplishments

During World War I, Elizebeth Smith Friedman and her husband spent about four years working in the only cryptologic laboratory in the country, according to the National Security Agency. The U.S. Naval Institute additionally reports that the newlyweds were in charge of all codebreaking in the United States for the first eight months of the war.

Not only did they develop methodologies that are used to this day, but both proved their ability as codebreakers. The couple was asked to move to Washington D.C., where William worked in the Army Reserve Signal Corps and Friedman joined the Coast Guard, then part of the Treasury Department.

Though World War I had ended, the United States had a new problem on its hands. Following the start of Prohibition in 1920, the country was suddenly overwhelmed with bootleggers who were illegally smuggling alcohol. The Coast Guard wanted Friedman to help crack their codes.

George C. Marshall FoundationAfter World War I, Elizebeth Smith Friedman put her codebreaking talents to use during Prohibition.

“The government law enforcement agencies had no more taste for [enforcing Prohibition] than the public who loved their drink,” Friedman wrote of her new task. “But the government officials, who with minor exceptions were honest at least, had no choice but to pursue the rigid torturous paths of attempting to defeat the operations of the criminal gangs who were so intent on mulcting the public.”

Friedman soon found that her work investigating bootleggers was like child’s play; the smugglers used simple codes that were easy to crack. “When choosing a key word,” she wrote, “never choose one which is associated with the project with which one is engaged.”

She and her clerk solved approximately 12,000 encryptions during Prohibition. Time reports that her codebreaking resulted in 650 criminal prosecutions and that Friedman testified in some 33 court cases.

“Mrs. Friedman made an unusual impression,” Colonel Amos W. Woodcock, Special Assistant to the Attorney General, wrote of one of Friedman’s testimonies, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

“Her description of the art of deciphering and decoding established in the minds of all her entire competency to testify.”

But Elizebeth Friedman’s greatest accomplishments were still ahead.

Elizebeth Smith Friedman During World War II

Elizebeth Smith Friedman’s work during WWII was often frustrating. First, the Navy took over the Coast Guard in 1941 and demoted her because of her gender. Second, Friedman was assigned to break the codes of Nazi spies in South America but, according to History, desired to work on the more complex codes used by the Japanese and the German governments.

Nevertheless, Friedman got to work. Her task was to spy on Nazis who the U.S. feared would encourage coups in South America, destabilizing the region. This job was made significantly more difficult when FBI director J. Edgar Hoover tipped off the Nazis by prematurely launching a raid and exposing the intelligence operation in place.

Keystone/Getty ImagesJ. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, made Friedman’s work more difficult and also took credit for her accomplishments.

Despite this setback, Friedman prevailed. U.S. Naval Institute reports that she located the Nazi network in South America, deciphered 4,000 typed messages, mastered 48 radio communications, and broke three Enigma codes. Though the Nazis had changed their ciphers after Hoover’s raid, Friedman and her team were able to crack the Nazis’ new codes.

But Friedman rarely got the credit. Smithsonian Magazine reports that Hoover took the credit for much of her success, and the U.S. Naval Institute notes that Coast Guard Lieutenant Commander Leonard T. Jones — who Friedman had trained — was also recognized instead of her.

Indeed, Friedman’s accomplishments went unnoticed. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, her family’s Christmas letter of 1944 announced that William Friedman had been awarded the Exceptional Service Award with Gold Wreath — Friedman, it said, had been working a “routine navy job.”

The Legacy Of The ‘Mother Of Cryptology’

Daderot/Wikimedia CommonsElizebeth Smith Friedman and her husband, William. Both were accomplished codebreakers.

By the time she died in 1980, Elizebeth Smith Friedman had said little about her accomplishments. Indeed, Time reports that she took a Navy oath promising to not reveal the full details of her work during her lifetime.

But all that changed in 2008 when many files concerning Friedman’s work were declassified. Suddenly, her accomplishments as a codebreaker during World War I, World War II, and Prohibition came to light.

Today, she’s recognized alongside her husband as one of the most influential codebreakers in American history. Friedman is even sometimes referred to as the “Mother of Cryptology” for her role in developing codebreaking.

Her love of Shakespeare led Elizebeth Smith Friedman on some incredible adventures. And now, more than four decades after her death, this American codebreaker is finally getting her due.

After reading about Elizebeth Smith Friedman, look through these stunning photos from World War II that bring the conflict to life. Or, discover the little-known story of Queen Elizabeth II’s role during WWII.