In 1914, Ernest Shackleton was determined to cross Antarctica. But when ice trapped his ship Endurance, his mission instantly changed from exploration to pure survival.

Library of CongressIn the early 20th century, Sir Ernest Shackleton ventured into the frozen depths of the Antarctic, most famously aboard the Endurance from 1914 to 1916.

“Give me Scott for scientific method, Amundsen for speed and efficiency, but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

This was Sir Raymond Priestley’s assessment of Ernest Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer whose legendary adventures during his lifetime have become even more revered since his death.

By 1914, it was too late for Ernest Shackleton to be the first person to reach the South Pole; Roald Amundsen had earned that honor three years earlier.

Nevertheless, Shackleton still fostered an ambition to have his name forever tied to that vast, brutal, beautiful icescape. So that year, he set off for Antarctica with a new goal: to be the first man to cross the entire continent and to do so entirely on foot. “From the sentimental point of view, it is the last great Polar journey that can be made,” Shackleton declared.

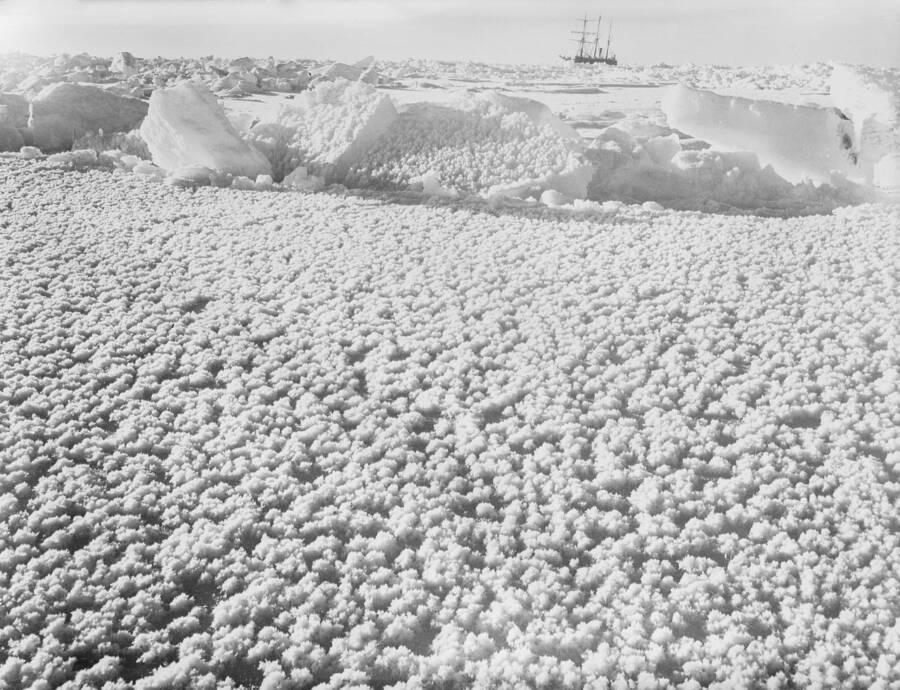

Getty ImagesErnest Shackleton’s ship, Endurance, trapped in ice.

But as fate would have it, Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, would never reach the frozen continent. Shackleton’s expedition failed — and yet the story of how his men survived on the ice for 497 days transformed the Endurance into one of the most memorable accounts of perseverance and resilience in history.

Ernest Shackleton’s First Expeditions To The South Pole

Ernest Shackleton was born in Kilkea, Ireland in 1874. When his family relocated to London, a 16-year-old Shackleton joined the merchant navy, dashing his father’s hopes that he would follow in his footsteps as a doctor.

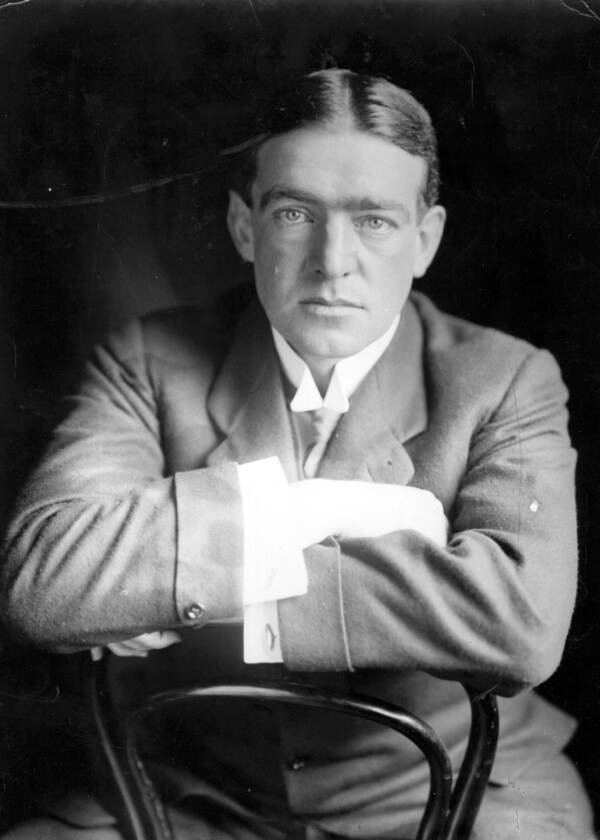

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAntarctic explorer Ernest Henry Shackleton. Circa 1910.

Driven by a desire to explore, Shackleton joined the 1901 Antarctic expedition led by Robert Scott, best known as the leader of the Terra Nova Expedition. Shackleton and Scott braved sub-zero temperatures to approach the South Pole, but fell short.

A few years later, in 1907, Ernest Shackleton led his own expedition to the South Pole on the Nimrod. To aid their journey, the explorers brought a grab bag of performance-enhancing drugs, which included “Forced March” pills, a cocaine/caffeine blend to be popped when heightened stamina was needed.

Although this expedition came closer than any previous attempt, Shackleton decided to turn back when he was just 97 miles short of the pole. He knew that being the first to ever reach the pole was in his grasp, but with supplies dwindling, he also knew the return would mean certain death for his men.

Abandoning his endeavor, Shackleton would leave behind three cases of Scotch — “Rare old Highland malt whisky, blended and bottled by Chas. Mackinlay & Co.” — which would remain lost in the Antarctic permafrost for nearly 100 years until it was recovered by a New Zealand conservation team.

Wikimedia CommonsErnest Shackleton with the Royal Naval Reserve at age 27.

Despite falling short of his destination, Ernest Shackleton was awarded the rank of knighthood by King Edward VII for his efforts. It would be six years before Shackleton would make another attempt at reaching the pole.

The Endurance Sets Off Toward The Frozen Depths Of Antarctica

On Saturday, Aug. 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia, and in a little over four weeks time, the first battle of World War I would commence. This would be the same Saturday that Ernest Shackleton started his voyage to march the length of Antarctica, leaving London and the the wider world behind — as it began its own fervent march toward mass death.

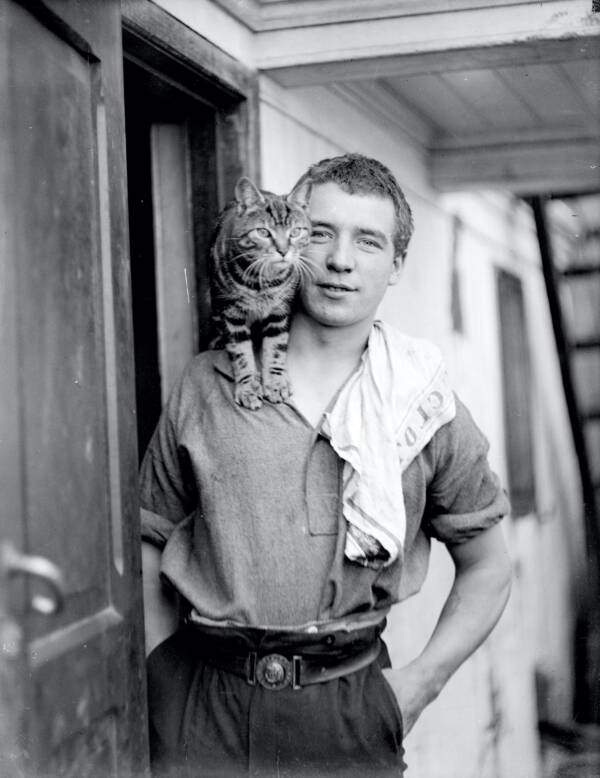

Frank Hurley/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty ImagesWelsh sailor and stowaway Perce Blackborow and Mrs. Chippy, the Endurance‘s cat.

Shackleton named his ship Endurance, borrowing from his family motto: “By endurance we conquer.”

Aboard the 300-ton ship, which carried sails and a steam engine, were Ernest Shackleton’s hand-picked crew of 26 men, 69 sled dogs, and a tiger tabby tomcat named Mrs. Chippy. By late October, one stowaway, 20-year-old Welshman Perce Blackborow, who had been shipwrecked off the coast of Uruguay, climbed aboard the Endurance before it departed Buenos Aires.

Upon discovering the stowaway three days later, Shackleton flew into an explosive tirade. Drawing to his close, Shackleton growled, “Do you know on these expeditions we often get very hungry, and if there is a stowaway available he is the first to be eaten?”

“They’d get a lot more meat off you, sir,” retorted Blackborow.

Stifling a smile, Ernest Shackleton sent the sneak to meet the ship’s cook and would shortly thereafter make him a steward of the ship.

By November 1914, the Endurance reached South Georgia, a whaling isle that served as the last port before Antarctica. The whalers warned Shackleton of treacherous conditions in the Weddell Sea. Unusually thick pack ice stretched for miles, the most they’d ever seen. Not heeding their warnings, Shackleton ultimately decided to press on.

On December 5, the Endurance set out. Two days later, the ship struck ice. For six weeks, Shackleton’s crew piloted the ship between loose ice floes.

James Francis Hurley/National Maritime MuseumThe Endurance, seen across newly formed ice.

“Pack-ice might be described as a gigantic and interminable jigsaw-puzzle devised by nature,” Ernest Shackleton later wrote in South, his book on the expedition.

The ice slowed the journey. Frank Worsley, who captained the ship, wrote, “All day we have been utilizing the ship as a battering ram.”

Ernest Shackleton And His Crew Spend Nine Months Trapped In The Ice

The crew of the Endurance didn’t know it, but they were mere days away from disaster. On January 18, the ship sailed into dense pack ice. Ernest Shackleton and Worsley decided to not use their steam engine to push through and waited instead for an opening to appear.

Overnight, the ice sealed around the ship, trapping it “like an almond in the middle of a chocolate bar” as one crewman put it, and carried the Endurance out to sea.

They were only one day shy of their landing point on the continent. For the next nine months, the Endurance drifted along with the ice floe, unable to escape its entrapment.

Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer, later wrote, “How dreary the frozen captivity of our life but for the dogs.” While the cat remained onboard, the dogs moved to “ice kennels” or “dogloos” built next to the ship. The men made the best of their situation. They exercised their sled dogs, played soccer on the ice, and explored the frozen ice sheet surrounding them.

Frank Hurley/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty ImagesThe crew plays soccer on the floe while they wait for the ice to break up around the Endurance.

The Crew Abandons The Endurance And Sets Off Across The Ice

As the months passed, the ice slowly crushed the ship. On October 27, almost a year to the day since they’d departed Buenos Aires, the men were forced to abandon the Endurance.

Leaving the Endurance behind, the crew set up a camp on the ice, dubbed “Ocean Camp.” Ernest Shackleton made sure the sailors received the warmest sleeping bags, while he and the officers took the draftier ones. They slept on the ice in thin linen tents – so thin the sailors could spy the moon through the tents’ fabric.

“It is beyond conception, even to us, that we are dwelling on a colossal ice raft, with but five feet of water separating us from 2,000 fathoms of ocean, & drifting along under the caprices of wind & tides, to heaven knows where,” Hurley wrote in his diary.

Recalling that first night out on the ice, Captain Worsley would write, “I remember asking myself why people had always pictured Hell as a place that was hot. I felt certain that if there were any such place it would be cold — cold as the Weddell Sea, cold as the ice which seemed likely to become our grave.”

Royal Geographic SocietyThe Endurance sinking into the ice.

Three days later, as the men made ready to march to land, Ernest Shackleton decided to purge the expedition of any unneeded encumbrances. As a demonstration to his men, he left behind his gold watch and a Bible gifted to him by the Queen consort of the United Kingdom.

One of his men, Thomas McLeod, a devout Catholic, scooped up the scripture and kept it in secret, thinking it bad luck to do otherwise.

The previous September, the ship had turned around for Mrs. Chippy after the cat had leapt overboard. Mrs. Chippy had been stranded in the ocean’s icy waters for a full 10 minutes before the crew was able to rescue the pet. But new circumstances brought new priorities; Shackleton had three of the youngest pups shot along with the cat.

Mrs. Chippy had belonged to Henry “Chippy” McNish, the ship’s carpenter, who at 40 years of age was the eldest member of the crew, a two-time widower, and a life-long socialist who abhorred profanities.

Days after the murder of his cat, McNish attempted to stage a small mutiny against Ernest Shackleton, claiming that the ship’s articles no longer applied after the ship’s abandonment and he thus no longer had to follow Shackleton’s orders.

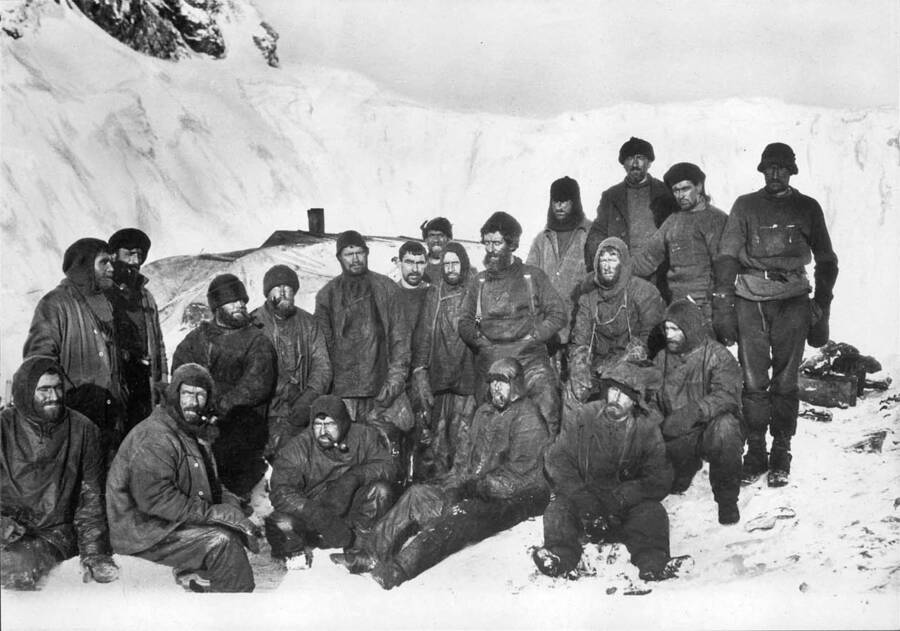

Library of CongressErnest Shackleton and the crew of the Endurance set sail for Antarctica in 1914. After disaster struck, it would be 497 days before they touched land again.

Pistol at the ready, Shackleton threatened to shoot McNish. The carpenter relented but Shackleton later wrote in his diary: “Everyone working well except the carpenter. I shall never forget him in this time of strain and stress.”

As Food Runs Short, Shackleton And Company Pile Into Lifeboats

The men escaped the Endurance with all the food they could tow — it would only be enough to last them four weeks.

“A few boxes of army biscuits soaked with sea-water were distributed at one meal,” Shackleton wrote. “They were in such a state that they would not have been looked at a second time under ordinary circumstances.”

With their food supply depleted, they began hunting penguins and seals. Once attacked by a leopard seal, Frank Wild, Shackleton’s next in command, shot the animal and discovered a trove of undigested fish in its guts, allowing for a delicious feast shared by the whole crew.

To celebrate leap day, the men had three full meals. Orde-Lees, the crew’s motor expert and future parachute enthusiast-turned-climber of Mount Fuji, laid out the specifics:

“For breakfast we had large tender seal steaks and a spoonful of fried dried onion each… Luncheon: penguin liver, one dog-pemmican bannock each, one-quarter of a tin of Lax (smoked salmon in oil) each and a pint of dried skimmed milk. Supper: a stew made from seal meat to which was added six 1lb tins of Irish stew and one of jugged hare, which we had been keeping for weeks especially for this occasion.”

By the end of March, more than a year after becoming trapped on the ice, the men had been forced to eat all of their sled dogs. To make matters worse, the ice below their camp had thinned; it would crack at any moment.

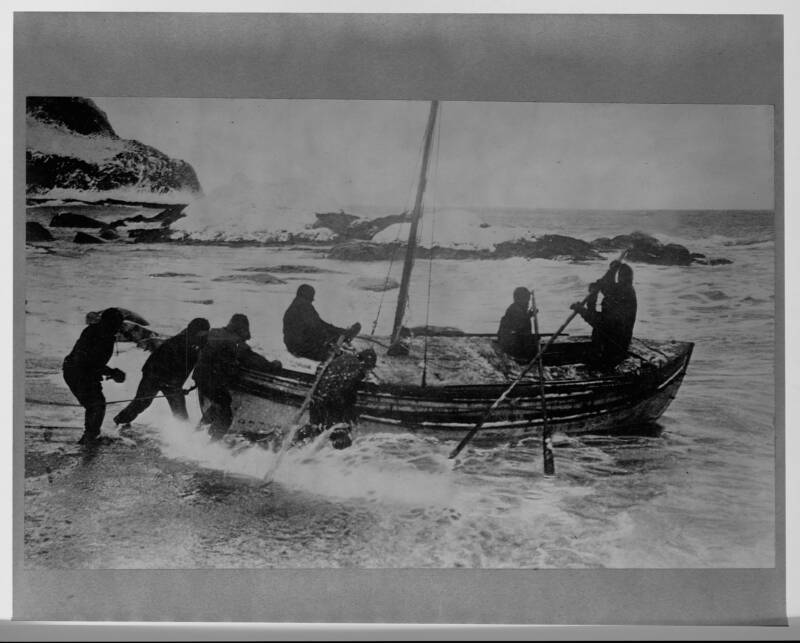

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesMembers of Ernest Shackleton’s expedition pull a lifeboat across the ice after losing their ship.

On April 9, 1916, the crew, still 28 men including Shackleton, climbed into three lifeboats they had saved from the Endurance. They left the ice, sailing toward a tiny, barren piece of land called Elephant Island. After seven days at sea, the crew finally reached land for the first time in 16 months.

Ernest Shackleton Travels 800 Miles In A Lifeboat

No one knew that Ernest Shackleton and his crew were trapped on Elephant Island. Facing possible death, Shackleton gambled on another sea voyage: back toward South Georgia.

The journey was 800 miles, and he only had a single lifeboat, the James Caird. The Caird‘s seaworthiness had been maintained by the efforts of McNish. He had caulked the boat with a mixture of flour, oil paint, and seal blood. He raised the vessel’s gunwales to make it safer for high seas.

Facing blizzards, stormy seas, and unimaginable odds, Shackleton and five other men set off.

Hurley/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty ImagesThe men left behind on Elephant Island when Ernest Shackleton and five others departed on the James Caird.

Frank Wild was left in command of the party left behind. “We gave them three hearty cheers & watched the boat getting smaller & smaller in the distance. Then seeing some of the party in tears I immediately set them all to work.”

Sailing nonstop for two and a half weeks, the six aboard the James Caird suffered from bleeding sores and saltwater boils; they were all frostbitten to different degrees and continuously wet. Frank Worsley tried to chart a course using a sextant and no landmarks. Over the 17-day period, Worsley could only take four sextant readings.

If the James Caird missed South Georgia, it would doom their crew of six and the lives of the men left behind on Elephant Island.

On May 5, catastrophe loomed. Shackleton wrote:

“I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then a moment later I realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave. During twenty-six years’ experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic. It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted, ‘For God’s sake, hold on! it’s got us.’ Then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived through it, half full of water, sagging to the dead weight and shuddering under the blow. We bailed with the energy of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides with every receptacle that came to our hands, and after ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life beneath us.”

On May 10, 1916, the James Caird hit land – South Georgia. Dubbed a miracle of navigation, the 800-mile journey has been called the greatest boat journey ever accomplished.

Shackleton Leads The Final Stages Of The Daring Rescue Mission

Ernest Shackleton’s rescue mission wasn’t over. The lifeboat had landed on the uninhabited western shore of South Georgia Island; reaching the whaling station on the island’s eastern side would require hiking the island on foot.

“The final stage of the journey had still to be attempted,” Shackleton wrote. “Over on Elephant Island 22 men were waiting for the relief that we alone could secure for them. Their plight was worse than ours. We must push on somehow.”

Shackleton, Worsley, and another man, Tom Crean, readied themselves to leave the other three men behind and hike more than 20 miles of uncharted land rife with mountains and glaciers. They brought three days worth of rations; any more would be too much of a burden for the final leg of their journey. McNish took brass screws from the Caird and affixed them as spikes to the three’s shoes.

After marching 36 straight hours, the three men — ragged, haggard, and smeared with blubber soot — finally reached the whaling community on May 20, 1916. When Shackleton told the station manager who he was, a whaler within earshot began to weep.

Shackleton then had to find a ship to return to Elephant Island. Yet ice once again made it impossible to reach his Antarctic destination. For months, Shackleton made multiple rescue attempts, all of which failed.

Shackleton worried, “If anything happens to me while those fellows are waiting for me, I shall feel like a murderer.”

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty ImagesErnest Shackleton leads a rescue attempt for his men stranded on Elephant Island.

Finally, on his fourth attempt, Shackleton reached Elephant Island. It was Aug. 30, 1916 — four months had gone by since he’d left.

When the rescue mission spotted Elephant Island, Shackleton pulled out his binoculars, counting the men on the beach. “They are all there!” he cried.

Ernest Shackleton Finally Returns Home

Ernest Shackleton and his crew returned to London in October 1916, more than two years after leaving. Every single crew member of the Endurance had survived.

But another ship had yet to return; the Aurora had also set sail in August of 1914, commissioned to lay out food and fuel supplies for Shackleton’s intended trek across Antarctica.

Ten members of the Aurora‘s crew, the Ross Sea Party, left their ship, and marched 1,561 miles across the Antarctic wastelands, leaving supplies for Shackleton and his men, sometimes enduring blizzard winds that would plunge to -92 degrees Fahrenheit.

As time wore on, the party’s own food supply started running thin; in desperation, the team’s huskies devoured their leather and metal harnesses. One by one, all but three of the 26 dogs died from stress and starvation.

The Aurora itself was blown out to sea by a storm and trapped in ice from May 1915 to March 1916, leaving the team of 10 stranded. After the ice finally melted, the Aurora was able to dislodge and resupply in New Zealand. The ship would not be able to rescue the Ross Sea Party until Jan. 10, 1917.

When one of the stranded, Andrew Keith Jack, realized that a ship was approaching, he cried “tears of joy” believing the news to be “too good to be true.” Aboard the Aurora was Ernest Shackleton himself; he was soon to discover that three of the 10 had died, including the ship’s captain, Aeneas Mackintosh, who had sailed with Shackleton on the 1907 Nimrod expedition.

Biographer Hugh Robert Mill wrote Shackleton’s “heart was heavy within him to find that disaster had befallen this section of his expedition, though he was filled with pride, too, by the way in which the work they were sent to do had been done.”

The Legacy Of Ernest Shackleton And The Endurance

Library of CongressErnest Shackleton, circa 1917-1920, in his final chapter between the return of the Endurance and his untimely death at age 47.

The Polar Medal, bestowed by the United Kingdom, is awarded to those who have made significant achievements in the realm of polar exploration.

When Ernest Shackleton was asked to present a list of recipients from the Endurance and Aurora crews for the award, he listed everyone save three trawler-men and Henry McNish. True to his word, Shackleton never forgave McNish for the insubordination he showed on the ice floe in 1915.

Shackleton would go on to receive more medals and awards than any other polar explorer before or since; McNish would receive nothing.

Just as nearly every member of Shackleton’s crew received a Polar Medal, so too did nearly all join the war effort during World War I; two were killed in the war.

Popular Mechanics MagazineErnest Shackleton’s final voyage to Antarctica on the Quest.

In 1921, Shackleton once again set out for the Antarctic, this time on the Quest still hoping to reach the South Pole. When the party reached Rio de Janeiro, Shackleton experienced what was likely a heart attack, but he refused a medical examination.

By the time they reached South Georgia on Jan. 4, 1922, Shackleton’s condition had worsened. By his bedside that night was Alexander Macklin, the ship’s doctor. Shackleton said to him, “You’re always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to give up?”

“Chiefly alcohol, boss, I don’t think it agrees with you,” responded Macklin. Shortly after the exchange, Ernest Shackleton had another heart attack and died suddenly around 2:50 a.m. on January 5, a little over a month short of his 48th birthday. Shackleton was buried in South Georgia.

As for McNish, he was left unable to work due to an injury and took to sleeping in a wharf shed and surviving on a monthly collection provided by wharf laborers. He eventually took up residence at a charity rest home. As his death neared in 1930, McNish was approached by an Antarctic historian, who said: “He lay there repeating over and over again: ‘Shackleton killed my cat.'”

McNish was given a naval funeral and buried in a pauper’s grave in New Zealand. In 1959, the New Zealand Antarctic Society, the same group which would recover Shackleton’s abandoned whisky nearly 50 years later, erected a headstone over the carpenter’s grave, misspelling his name as “McNeish.” In 2004, a bronze statue of Mrs. Chippy was added to the grave.

Wikimedia CommonsLegendary Anglo-Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton led several daring expeditions to Antarctica between 1901 and his sudden death at 47 in 1922.

In South, Ernest Shackleton would sum up the Endurance expedition as such:

“In memories we were rich. We had pierced the veneer of outside things. We had ‘suffered, starved, and triumphed, groveled down yet grasped at glory, grown bigger in the bigness of the whole.’ We had seen God in His splendours, heard the text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of men.”

Ernest Shackleton’s voyage never reached its destination, but he still made history. Next, read about other explorers who changed the world, and then check out vintage photos of Antarctic expeditions.