Eunice Foote's amateur experiments were the first to outline the relationship between greenhouse gasses and atmospheric warming, but a male scientist with a similar experiment took credit for the find three years later.

NOAAEunice Foote’s work has received renewed attention after a private collector stumbled upon a sample of it in Scientific American.

Climate science is a crucial branch of scientific study and is perhaps even more so now than ever with the growing concern for global climate change.

But little know that the first person to identify how greenhouse gasses affect our atmosphere was an amateur American scientist and 19th-century suffragist named Eunice Foote.

It would take over a century for Foote to receive the credit she deserved for her astounding contributions to science and women’s rights.

The Forgotten Work Of Eunice Foote

Wikimedia CommonsEunice Foote was educated at Troy Female Seminary which is now called the Emma Willard School in Upstate New York.

Little is known about Eunice Foote’s personal life and background, but researchers have uncovered a few things about the climate scientist.

She was born under the full name Eunice Newton Foote in 1819 and mostly lived her life in Upstate New York.

She attended Troy Female Seminary (which is now called the Emma Willard School) whose students were encouraged to attend a nearby science-based college where she likely picked up the skills that would aid in her independent experiments.

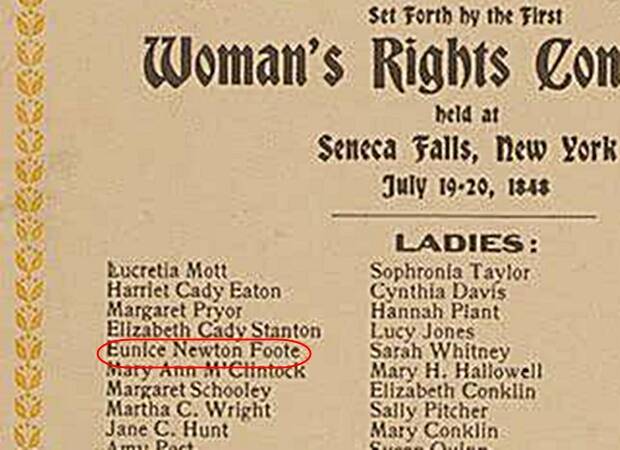

But Foote’s interests extended beyond science; she was friends with prominent suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton and was a proud suffragist herself. Indeed, her signature even appears on the Declaration of Sentiments drawn up by suffragists at the 1848 Seneca Fall convention for women’s rights.

Wikimedia CommonsEunice Newton Foote’s signed name on the Declaration of Sentiments, right below Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s.

But most importantly, Foote was the first scientist to define the greenhouse gas effect. She was the first person to demonstrate how different proportions of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would change its temperature.

But Foote was prohibited from reading her findings to the other members of the 1856 American Association for the Advancement of Science conference in Albany, New York.

Instead, another scientist, a man, of course, swept in three years later to take credit for her work.

Foote Defined The Greenhouse Effect

Eunice Foote had conducted a series of independent science experiments to test whether the sun’s rays had any effect on various gases. She tested her theory using simple tools: an air pump, two glass cylinders, and four thermometers.

Foote filled each of the glass cylinders with two thermometers. Then, she used the air pump and removed the air from one cylinder, and condensed it in the other. After adding a bit of moisture, she then placed the cylinders under the sun.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesFoote’s 1856 paper was the first in history to publicly theorize on what we now call the “greenhouse gas effect.”

After testing a variety of gases, including carbon dioxide — which was in the 19th century referred to as “carbonic acid” — Foote theorized that the amount of these gasses in the atmosphere would have an effect on the atmosphere’s temperature.

This was the first time that the greenhouse gas effect had ever been described.

Meanwhile, Foote was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), which was among the few institutions that allowed amateurs and women to become members.

So in August 1856, Eunice Foote presented her paper titled Circumstances Affecting the Heat of Sun’s Rays at the annual conference of the AAAS. Foote’s presence there was the first recorded account of her scientific endeavors.

But Foote did not get to present or read her paper herself. Instead, Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution editorialized Foote’s study, saying that “science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful but the true.”

Whether this was meant to be a compliment to Foote’s endeavors or a way of protecting her from sexist criticism is anyone’s guess, but either way, Foote’s work wasn’t read in full or with the seriousness it deserved.

Foote’s study was omitted from the society’s annual Proceedings where all the works that were presented at their annual meetings were published.

Thus, in 1859, Irish scientist John Tyndall published his own paper and has since been widely credited as the father of modern climate science.

Rediscovering The True Mother Of Climate Science

In 2011, Foote finally received the credit she so deserved.

When a collector of antique science journals named Raymond Sorenson stumbled upon a summary of Foote’s original 1856 study — which was briefly described in the scientific journal Scientific American — he took note.

There, in a special column titled Scientific Ladies was Foote’s independent research. It was praised by the journal’s editors as “practical experiments” and the editors condescendingly noted, “this we are happy to say has been done by a lady.”

But Foote’s paper was never treated as its own study nor was it ever published along with the rest of the scientific studies of that year. So Sorenson went ahead and wrote a paper on it, publishing her work himself.

“Eunice Foote deserves credit for being the first to recognize that certain atmospheric gases, such as carbon dioxide would absorb solar radiation and generate heat… [three] years before Tyndall’s research that is conventionally credited with this discovery,” Sorenson asserted.

The revelation of Eunice Foote’s erasure begs the question: did John Tyndall know about her study? It’s difficult to know for sure but so far there has been no concrete evidence to suggest that he did.

The only other copy of Foote’s paper published in its entirety, besides now in Sorenson’s work, was in The American Journal of Science and Arts.

Fortunately, centuries after Foote’s near-erasure from scientific history, women in science are enjoying greater gender equality across the field. This has proven especially true for women in the realm of climate science.

Her Legacy On Climate Change

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesAs global warming continues to spark eratic climate events, climate science is more signifcant now than ever before.

Yet, there’s a lot that hasn’t changed much, either. As of 2020, less than 30 percent of the world’s researchers are women, a gross underrepresentation that happens equally across all regions of the globe.

And according to the United Nations, women continue to be excluded from participating fully in the fields of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics).

It’s clear there’s still much to be done in order to achieve true gender equity for women in science. Let’s give justice to those silenced female voices in science, like the inimitable Eunice Foote.

Now that you’ve caught up on the world’s first-known climate scientist, Eunice Foote, read about the forgotten brilliance of Laura Bassi, one of history’s first female scientists. Then, discover the true story of Ada Lovelace, the world’s first computer programmer.