The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, marked not just the dismantling of a barrier, but a victory for freedom itself.

The winter of 1989 was a significant time in German history. After 28 grueling years, the infamous Berlin Wall — which was built in the 19660s to divide Communist East Germany from non-Communist West Germany — came toppling down. The fall of the Berlin Wall, however, started as something of an accident.

When a misinformed party boss told a crowd of Berliners that the strict regulations around crossing the border had been softened, near-chaos ensued as East Germans rushed the border. Unprepared guards eventually had no choice but to let citizens through and eventually, the opening of the borders led to the destruction of the Berlin Wall entirely.

Leading Up To The Fall Of The Berlin Wall

Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty ImagesStalin, Churchill, Attlee, Truman, and others at the Potsdam Conference.

The defeat of the Nazis at the end of World War II was followed by the occupation of Germany by Allied troops. The country was divided into four different occupation zones: the western two-thirds of Germany was split between the Americans, British, and French, while the Soviet Union occupied the eastern part.

The arrangement was settled in the Potsdam Conference between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Soviet Union Premier Joseph Stalin, and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But Berlin, the former capital, became a special case. The occupying powers agreed to place the city under joint four-power authority led by the Allied Control Council even though technically the city fell within the Soviet Union's occupation zone.

Since most of Germany's agricultural production was within the Soviet-occupied zone, the Soviets took over Germany's manufacturing and production facilities. They were also tasked with providing food to the rest of the occupied areas, but the Soviet's desire to push out the Allied forces won over their post-war agreements.

Entering The Cold War — And The Berlin Wall Goes Up

Dominique Berretty/Gamma-Rapho/Getty ImagesThe Deutsche Volkspolizei, or commonly known as the Volkspolizei or VoPo, was the national police force of the German Democratic Republic.

In June 1948, the Allies introduced a new currency. In retaliation, the Soviet Union cut all access to Berlin to squeeze out the Allied forces, leaving West Berlin without access to food and supplies from outside its borders.

The Allies' solution was to airlift 278,000 separate flights of supplies to Berlin that included roughly 2.3 million tons of food, coal, medicine and other necessities that were inaccessible because of the Soviet blockade.

The airlift operation was in part a humane act from the Allies and a geopolitical tactic to win over the support of the 2 million West Berliners in their attempt to establish control post-war Germany. The British declared food rationing in England so that grain from America could be diverted to feed the people in West Berlin.

"It was an essential step to say: 'If we want to establish a democracy, we have to make sure that democracy is able to feed the people,'" Acting Director of the Allied Museum in Berlin Bernd von Kostka explained in an interview.

But the price of democracy did not come cheap. The U.S. spent $48 million to accomplish the air delivery while England shelled out $8.5 million. Fifty-seven lives were lost during the operation, among them 27 Americans, 23 British, and seven Germans.

The Soviet blockade lasted 318 days, but Allied forces continued to airlift supplies into West Berlin even afterward as a precaution.

Later, Germany formally split into two independent nations and remained so until the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Years Of Separation

DPA/Picture Alliance/Getty ImagesBorder guards from East Germany converse with police from West Germany after the destruction of the Berlin Wall.

In June 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy sought to discuss the unresolved matter of Berlin. By this point, the issue spelled the possibility of an all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union. Kennedy tried to negotiate with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, but his plan did not go well.

Khrushchev took a hard-line position. "It is up to the U.S. to decide whether there will be war or peace," Khrushchev said, to which Kennedy responded: "Then, Mr. Chairman, there will be war. It will be a cold winter."

Indeed, the climate of the Cold War grew even chillier. Especially when on August 13, Berliners awoke to 40,000 East German building the Berlin Wall which would serve as the visible divider between the East and West.

The GDR claimed that the Berlin Wall — which stretched 96 miles around West Berlin with 13 frontier posts — was meant to be an "anti-fascist rampart" against the West Germans.

But the truth was that 3 million East Germans had already fled to the less oppressive West German territory since the border between the two separated states was closed, so the GDR wanted to make sure that nobody else could escape their domain. Thus, families and friends were forced to separate overnight.

The Berlin Wall started as a plain barbed wire fence and was later built into a concrete two-layer fortress that sandwiched an empty plot known as "death strip" which featured extra security measures, like sand beds, searchlights, barbed wire, armed vehicles, and electric alarm systems. In total, there were 302 watchtowers along the Berlin Wall.

Before the Berlin Wall was built, Berliners on both sides of the city could move between the east and west reasonably freely, and even public transit lines continued to operate and carry passengers back and forth. After the wall was built, however, it became almost impossible to go between East and West Berlin. Diplomats and other officials were screened at one of the 13 border checkpoints along the wall.

The frontier post bordering directly with the Allied territory was named "Checkpoint Charlie" and became the scene of a contentious standoff between East German tanks and Allied forces.

East Germany's guards were ordered to shoot on sight — including women and children — should they spot someone crossing the border illegally. But people were desperate. In all, an estimated 250 people were killed trying to make the crossing, though roughly 5,000 managed to escape safely.

The Fall Of The Berlin Wall

Scherhaufer/ullstein bild/Getty ImagesCrowds gather at the border in anticipation of the Berlin Wall's destruction.

Surprisingly, the fall of the Berlin Wall did not happen through rigorous political negotiations. Instead, it came about through a mistaken and premature announcement.

On November 9, 1989, GDR spokesman Günter Schabowski spontaneously announced that restrictions on travel visas to West Germany would be lifted.

When asked for a timeline of the new policy to take effect, Schabowski answered: "Immediately, without delay." The announcement shocked everyone — especially the border officers who had not been aware of the plan.

The surprise announcement was not at all how the visa policy was supposed to be rolled out.

Indeed, the original visa policy would still require East Germans to go through a lengthy application process to cross the border. But Schabowski's premature statements had already gone to the press which reported the news with fervor.

The reports sparked thousands of East Berliners to head to the Berlin Wall. Checkpoint officers faced a swell of crowds that grew angrier by the minute as the borders had not been opened as was announced.

At the Bornholmer Street checkpoint, Chief Officer Harald Jäger was harangued by the masses waiting to cross the border. To make matters worse, Jäger's superiors had ordered him to keep the border crossing closed despite the growing mob of angry citizens.

According to Jäger's own account, his superiors refused to listen to his explanation of what was happening at the border

"I shouted down the phone: 'If you don't believe me, then just listen.' I took the receiver and held it out of the window," Jäger said in an interview about the night of the border opening. Eventually, the scene had grown too much for Jäger and his staff officers to handle. He decided to disobey orders and open the gate.

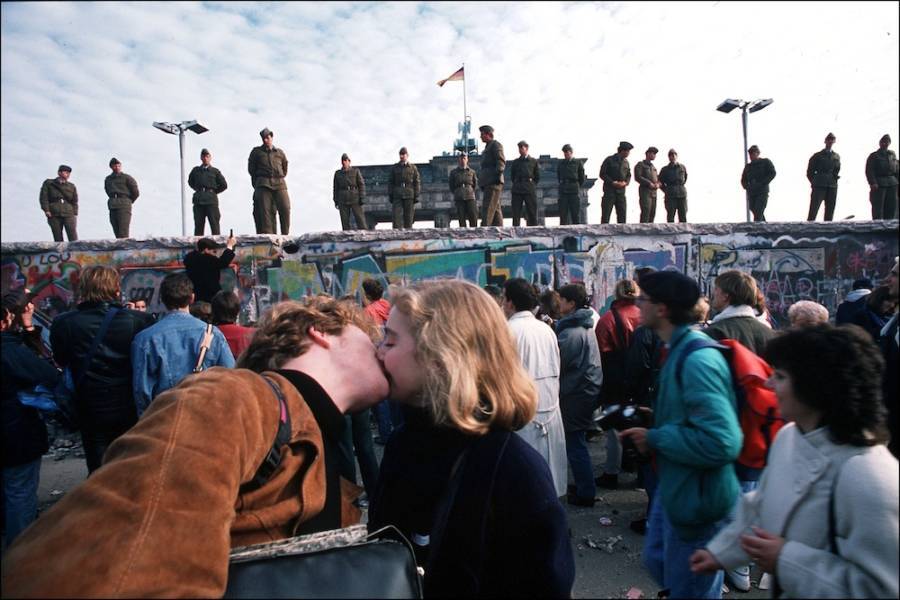

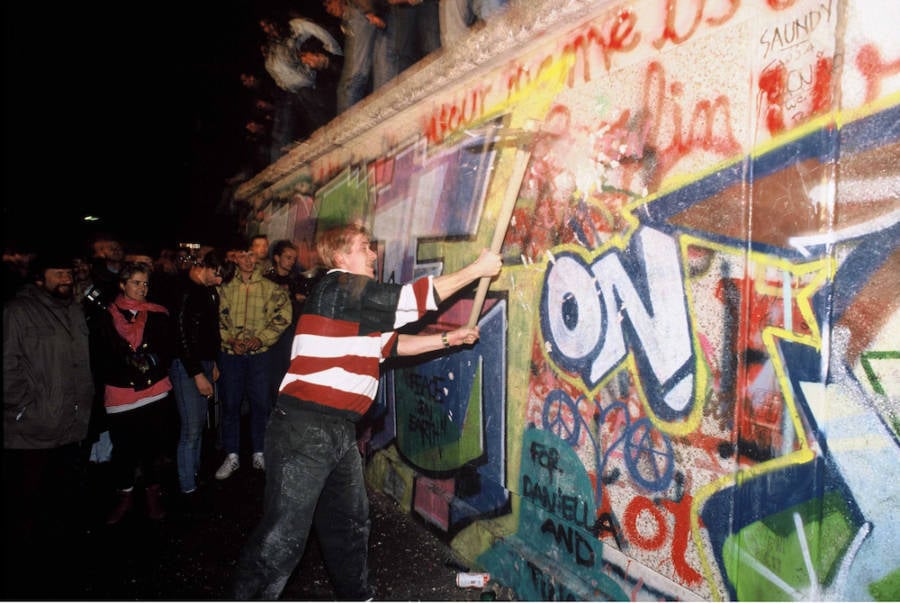

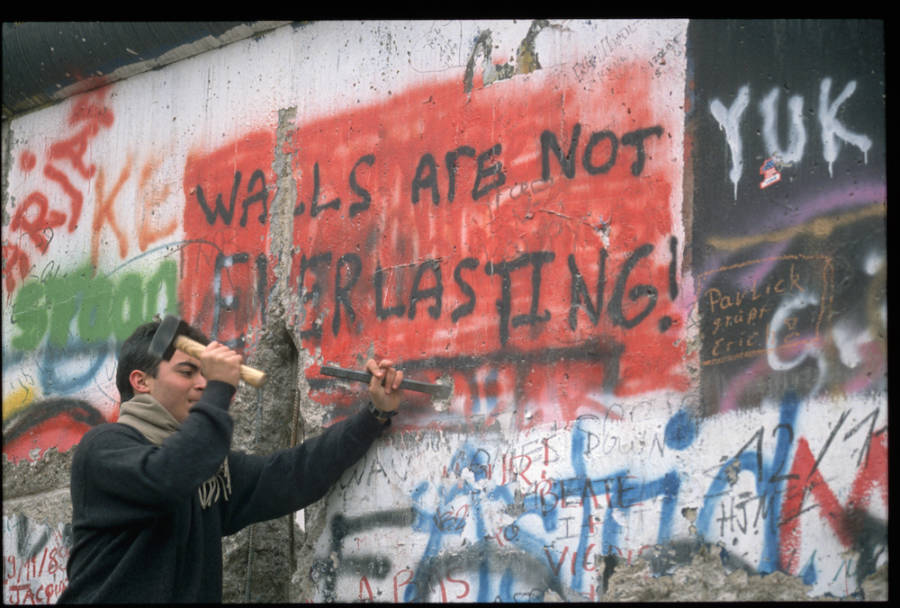

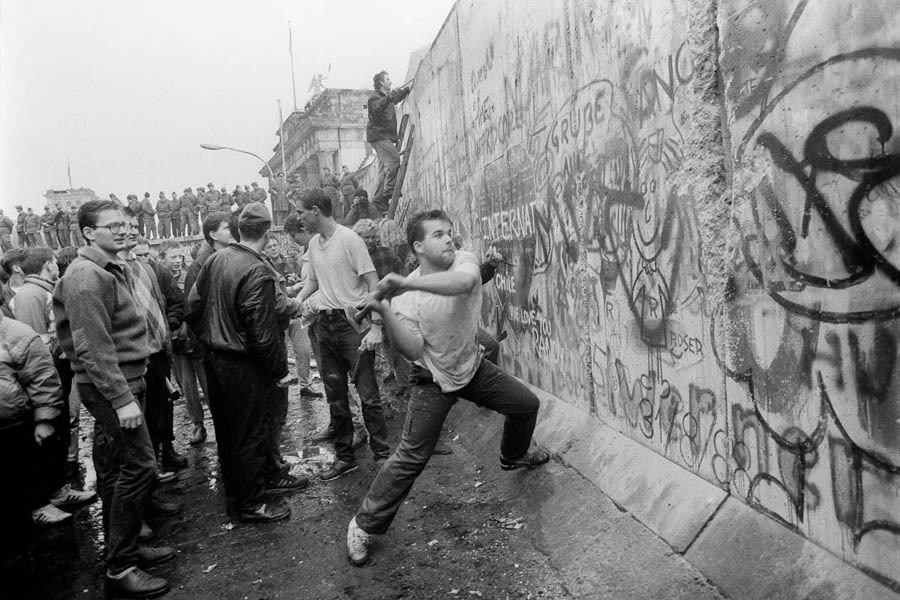

It didn't take long for the rest of the border security checkpoints to follow. Berliners from both sides rejoiced and celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall with sledgehammers, chisels, and celebratory drinks, hammering happily at the concrete barrier as a gesture of its destruction.

Crowds scaled the wall and cheered as their Eastern counterparts began to cross through the fallen border while reunited family members embraced and shed tears of relief.

Although the physical fall of the Berlin Wall can be attributed to a string of unplanned factors that happened overnight, the freedom that it granted East Berliners and Germans as a whole, was a long-fought battle.

As East German dissident-turned-politician Marianne Birthler put it, Westerners believe that "it was the opening of the wall that brought us our freedom." But "it was the other way around. First, we fought for our freedom; and then, because of that, the wall fell."

After this look at the fall of the Berlin Wall, learn how the Wall became a canvas for astounding artwork. Then, take a look at vintage photos that provide a peek into life in East Germany.