From Cold War spies to Aztec conquerors, these famous betrayals are a reminder that human history isn't marked solely by acts of goodwill.

March 15th, better known as the Ides of March, marked the first half of the first month of the year in the Roman Calendar. In 44 BC, it also marked one of history’s most notorious betrayals and brutal political assassinations: that of Julius Caesar by his friend, Brutus. In the spirit of betrayal, we’re looking at a few more shocking betrayals from history in celebration of the Ides: starting, of course, with Brutus and Caesar…

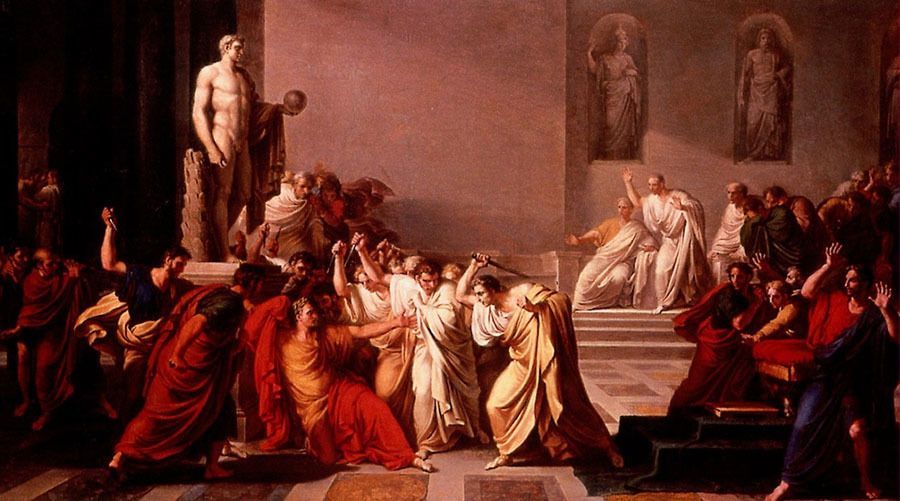

Brutus

The assassination of Caesar.

Despite being one of his closest friends, Brutus was among several disgruntled Roman senators who viciously stabbed Caesar to death. This was a betrayal of epic proportions, and one cemented in popular culture by Shakespeare’s classic line, “Et tu Brutus? Well, then fall Caesar…” in his play “Julius Caesar” (a line never actually uttered by Caesar himself, who, in all likelihood, was rendered incapable of speech by 23 stab wounds).

It was not a decision Brutus made lightly. He loved Caesar; he just loved the Roman republic more, and the rest of the senate used this loyalty to convince him that Caesar had to die for the Republic to be saved.

Historically speaking, they may well have been correct: Known for wielding his political power like a dictator — something the Senate resented — Caesar’s rampages were beginning to look as though he might dismantle the Roman republic entirely and rule, effectively, as king.

For Brutus, there was also the question of heritage. His ancestor (another Brutus) had been the one to overthrow the Roman monarchy in 509 BC, another fact the Senate used to their advantage, convincing Brutus that killing Caesar was his destiny. Whether or not it was truly fate, Brutus will be forever remembered as the ultimate backstabber for Caesar’s assassination.

Judas Iscariot

Judas kisses Jesus to identify him to the men who would crucify him.

Judas was one of the 12 Apostles of Jesus Christ, known mostly for offering to betray Jesus to religious authorities in exchange for 30 pieces of silver.

The New Testament describes how Judas took the soldiers to Gethsemane, where Jesus was praying, then kissed him to identify him as the Jesus. Legend also has it that Jesus knew Judas would betray him, but didn’t try to stop him.

Some accounts say that Judas regretted his betrayal, returned the money and committed suicide. Other accounts say that he died accidentally, having not returned the money. But the biggest mystery to bible scholars is just why the betrayal took place.

One popular theory suggests that Judas was motivated by greed. There are a lot of holes in that theory, though, the first being that in today’s money, the infamous 30 pieces of silver would be the equivalent of about $3,500 – not a huge amount to betray somebody you believe to be the son of God.

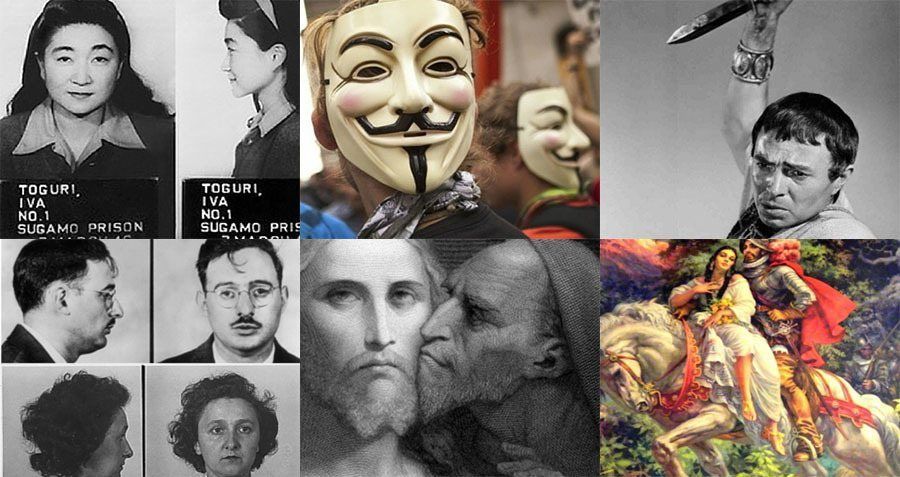

Gunpowder Plot Conspirators

Conspirators of the failed Gunpowder Plot. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Britain’s most notorious traitor, Guy Fawkes, is remembered for trying to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605. Following the persecution of Catholics at the hands of Elizabeth I and James I, Fawkes joined a motley crew (led by Robert Catesby) to take violent action in support of the subjugated religious sect.

Fawkes and his co-conspirators placed 36 barrels of gunpowder in the cellar beneath the House of Lords. But as they continued to work out the specifics, they realized a lot of innocent people would be killed if they did, in fact, blow up Parliament — some being those who also fought to defend the Catholics.

Several of the plotters started to have second thoughts, and one conspirator is thought to have written to Lord Monteagle to warn him to avoid Parliament on the 5th of November (remember, remember) — the day of opening, when the King would be present.

Fawkes, however, carried on with the plot and was captured in the bowels of Parliament with all his gunpowder, then sentenced to one of the worst executions imaginable by order of King James. The actual ring leader, Catesby, was never tried for his conspiracy to blow up Parliament, instead being killed while trying to make his escape.

Even though it was unsuccessful, the Gunpowder Plot became a major part of English history, and is commemorated every November 5th with firework displays and a historic bonfire, onto which a dummy Guy Fawkes (known simply as a “guy”) is placed.

Guy Fawkes himself became a symbol of Catholic extremism (even though he was born a Protestant) and despite his shake-up, the repression of the Catholics in England continued for another 200 years.

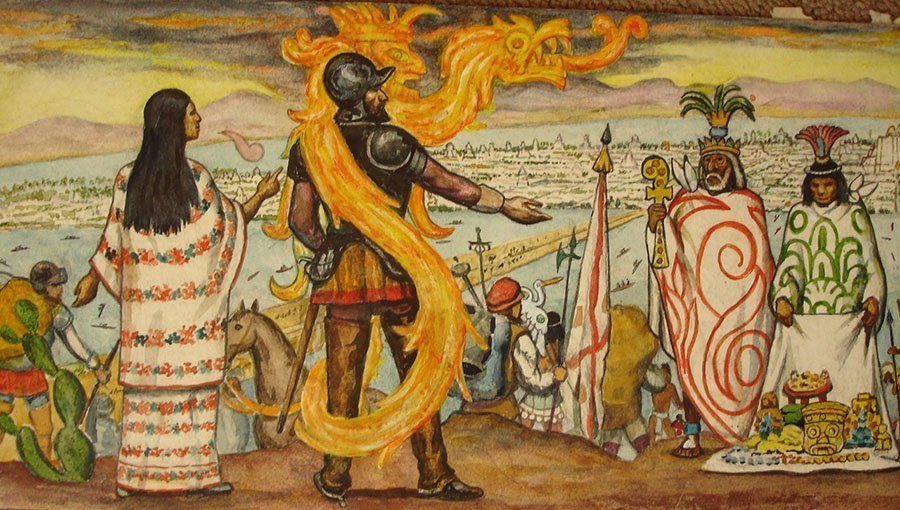

Doña Marina

La Malinche guides Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Doña Marina, a Nahua woman, was sold into slavery at a young age, and ended up working as a courtesan to Hernan Cortes as he and the Spaniards began their conquest of the Aztecs in 1519. Within a few weeks of her sale to Cortes, he realized that Marina had the linguistic skills necessary to serve as a translator<, being familiar with the Aztec language, as well as Mayan and Spanish. These skills made her an essential and valuable asset to Cortes, and he eventually fathered a son with her. To many indigenous tribes, and eventually some Mexican people, Marina was the ultimate traitor, a woman who betrayed her own people and used her unique position to inform Cortes' decisions and make his conquest possible. Even today, she is often to as La Chingada, which loosely translates as “the fucked one.”

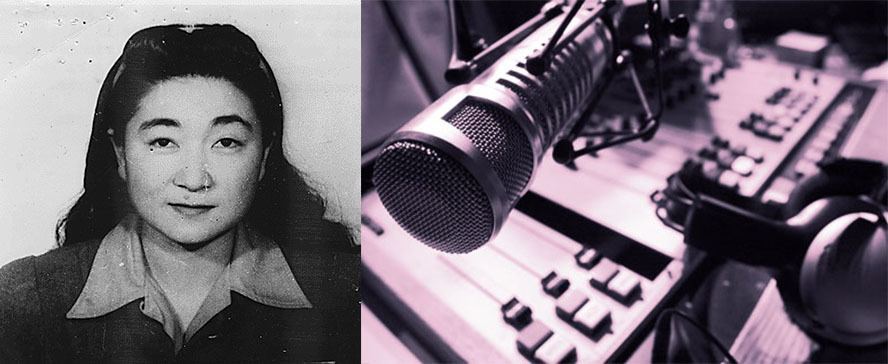

Tokyo Rose

Iva Toguri, the most famous “Tokyo Rose.” Image Source: Flickr

Tokyo Rose was a name given to several English-speaking women who broadcasted Japanese propaganda during World War II. Troops in the South Pacific used these women and their messages to lower Allied troop morale in the Pacific.

Despite reading anti-American scripts, Tokyo Rose the persona often prefaced her messages with subtle warnings and usually delivered them in a tongue-and-cheek manner, undermining the broadcasts’ intent.

The most famous name associated with Tokyo Rose is Iva Toguri, a Los Angeles native who had become stranded in Japan while visiting relatives at the start of World War 2. Her involvement as a propagandist got her arrested and convicted of treason, though she was released in 1956. It would be another 20 years before she would be formally pardoned.

Julius And Ethel Rosenberg

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of treason and sentenced to death by electric chair.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were an American couple accused of spying for the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Both Rosenbergs were from Jewish families in New York. They married in 1939, and Julius served in the military throughout WWII until he was discharged for previous involvement with the Communist Party.

Throughout the Cold War, the Rosenbergs provided thousands of top-secret reports on aeronautics and atomic bomb construction to the Soviets as well as recruiting sympathizers. Both Julius and Ethel were charged with treason and conspiracy to commit espionage, and in 1950, a federal grand jury indicted them.

Ethel was unable to complete her testimony and left the courthouse, her attorney begging for parole so that she could make arrangements for her two young children. The request was denied. Both Rosenbergs were pressured to incriminate any others who had been involved in the spy ring, but they provided no more information.

The trial began in March 1951. When asked about their involvement in the spy ring, the couple asserted their 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination. They were convicted and sentenced to death the following month, and were executed by electric chair on June 19th, 1953.

Decoded Soviet documents showed Julius had indeed been involved as a courier and recruiter for the Soviets, but Ethel’s involvement was not so clear. It seems that her brother, David Greenglass — who had worked on the Manhattan Project — had thrown her under the bus in his testimony to save his own wife, who had been the one typing up the documents.

In 2001, Greenglass recanted his testimony about Ethel, saying, “I frankly think my wife did that typing, but I do not remember.” He said he gave false testimony to protect himself and his wife, and had been encouraged by the prosecution to do so. Still, Greenglass felt no remorse, as he “would not sacrifice my wife for my sister.”

The Rosenbergs’ two sons, Michael and Robert, spent the majority of their lives trying to prove their parent’s innocence. They came to believe that while their father had likely been involved in espionage activities, their mother had really been innocent.

Next, check out these famous last words and history’s greatest insults.