These famous inventors don't actually deserve credit for the inventions that made them famous. Here's who we should be remembering instead.

While the light bulb may be the quintessential human invention — not to mention the very symbol of inspiration itself — the process of invention couldn’t be further from flipping a light switch. Invention is a slow, gradual grind, with one inventor carefully building off the achievements of the last until we finally have the product that history has decided is the invention.

However, once we have these inventions and the famous inventors supposedly responsible for them, we tend to forget those inventors that came before, and instead pretend that that last inventor in the chain conjured brilliance from nothing, turning darkness into light.

Worse yet, we sometimes ignore the inventor who should have been known as the last one in the chain. Often, those not-so-famous inventors are ignored because they aren’t from the right class, or don’t have enough clout, or aren’t from the right nation.

Whatever the reason, here are six famous inventors — including the man behind the light bulb itself — who don’t actually deserve credit for their most famous creation.

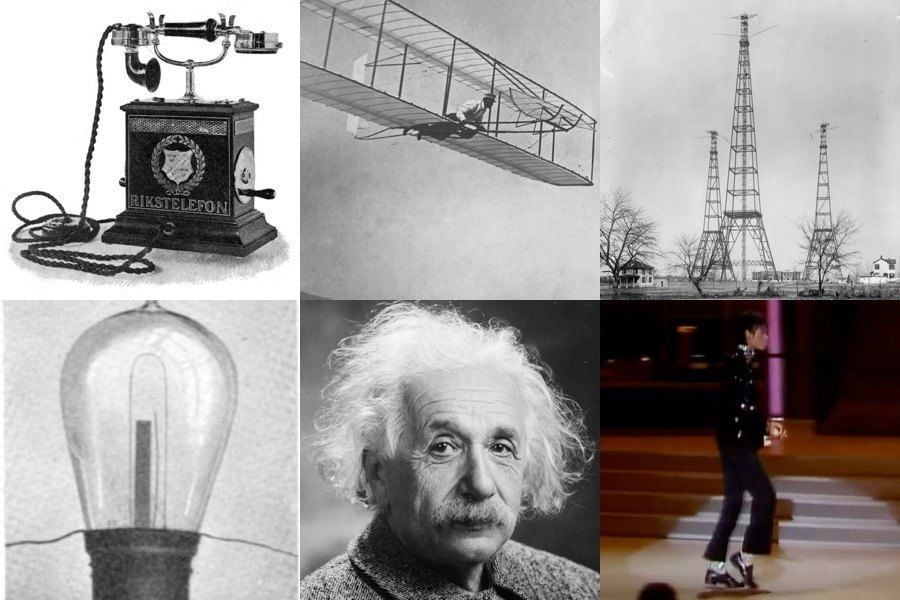

Famous Inventors: Alexander Graham Bell Didn’t Invent The Telephone

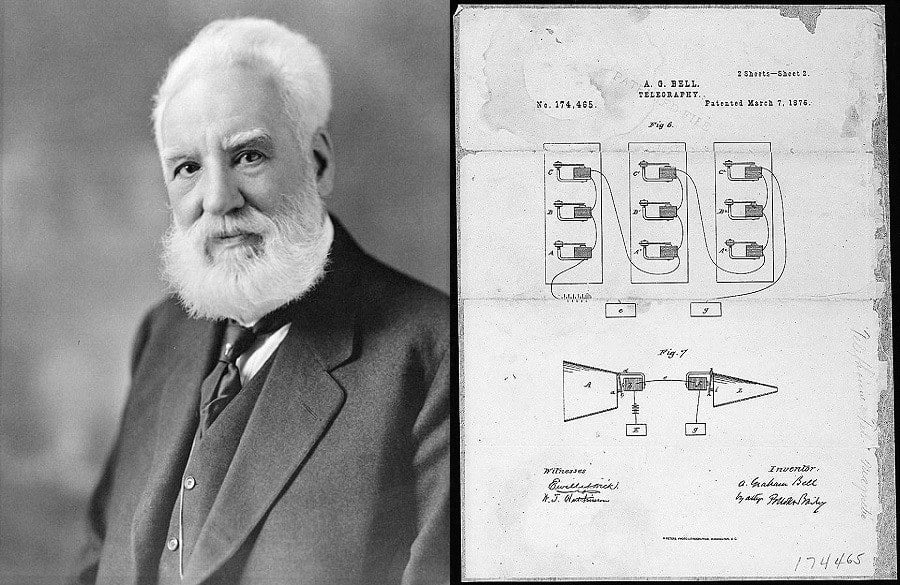

Left: Alexander Graham Bell, one of history’s most famous inventors. Right: Bell’s original patent drawing for the telephone. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons.

Why He Got Credit

On June 2, 1875, Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant, Thomas Watson, were working on their harmonic telegraph, a device that would transmit sound at a distance via the vibrations of steel reeds charged with currents. When one of the reeds failed to respond to a current, Bell, thinking the reed had stuck to the nearby magnet used to generate that current, asked Watson to pluck the reed with his hand. When he did, Bell actually heard the sound on his receiver far away. They’d successfully transmitted sound at a distance.

One month later, they transmitted the human voice (Bell saying “Mr. Watson — come here — I want to see you.”). After a few more months of tinkering and refining, on March 7, 1876, Bell was awarded U.S. Patent 174,465, and the origin story of the telephone, as we know it, came to an end.

Who Actually Deserves Credit?

Elisha Gray.

However, the true drama of this origin story happened nearly a month before that patent (tellingly titled “Improvements In Telegraphy”) was awarded. It was Valentine’s Day, 1876, and not one, but two, men were racing to the Patent Office. The one who got there first, however, wasn’t Alexander Graham Bell, but Elisha Gray.

Gray, a man whose name rarely ranks among the list of history’s most famous inventors, had been working on a sound transmitting device for years, similar to Bell’s except for its use of a liquid transmitter. And on the morning of February 14, Gray’s lawyer got to the Patent Office bright and early and handed in his paperwork — where it sat, at the bottom of the pile, until the afternoon. In the meantime, just before noon, Bell’s lawyer reached the Patent Office, and whether by force or clout, had Bell’s paperwork pushed through the pile and filed immediately.

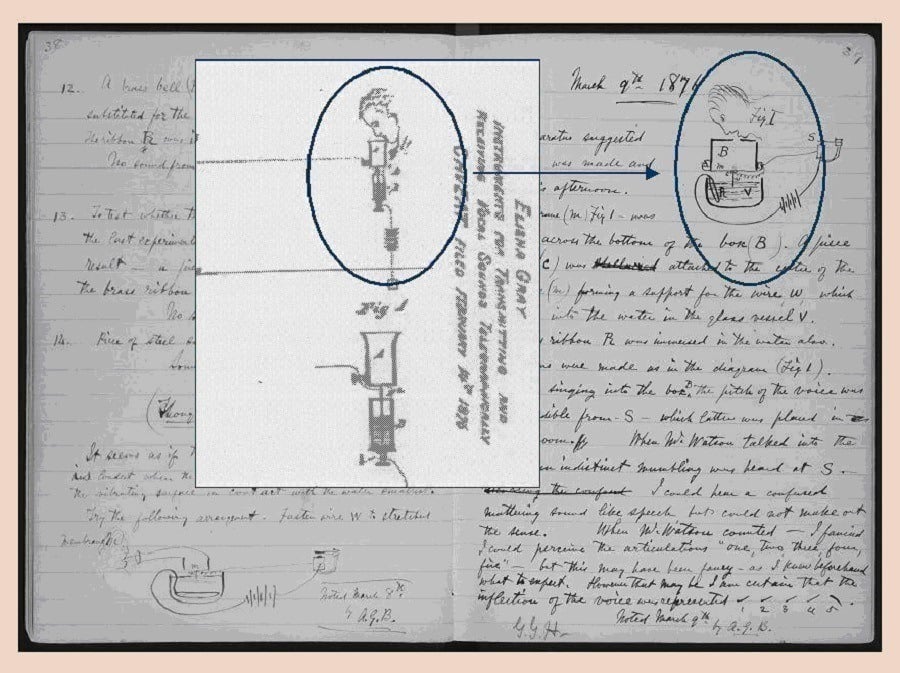

Excerpts from Gray’s patent caveat of February 14 (inset) compared with Bell’s notebook of March 8, highlighting the section Bell reportedly stole from Gray. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

And it’s not just that Gray got there first, it’s that many scholars claim that the paperwork Bell did file that day included a section (regarding that liquid transmitter and the use of variable electric current) that had been stolen from Gray’s work. The patent examiner who looked at both Bell and Gray’s paperwork, saw this red flag and suspended Bell’s application for 90 days while he reviewed the claims.

However, Bell and his lawyer were able to persuade the examiner to lift the suspension after they produced an earlier patent filing of Bell’s that showed the use of a liquid transmitter. That filing showed that both the liquid being used and the way it was being used were not applicable to the telephone. Nevertheless, the examiner was able to be convinced and the patent was Bell’s.

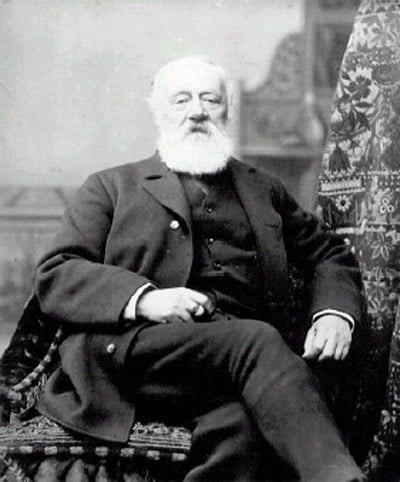

Antonio Meucci. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

And while Bell vs. Gray is certainly the most dramatic showdown in this whole tale, it also obscures the pioneering work of nearly a dozen men who could also lay claim to the telephone’s invention. Chief among them is Antonio Meucci (not among history’s most famous inventors, but among its most important), who had achieved success with primitive telephones all the way back in the 1830s, and was able to transmit his voice electromagnetically, as Bell eventually would, by the mid-1850s.

Meucci even filed a caveat (a formal intention to file a patent, as opposed to a complete filing) with the Patent Office in 1871 that essentially describes the device Bell would patent five years later. However, Meucci, who live in poverty most of his life, wasn’t able to afford the $10 caveat renewal fee in 1874. A 2002 U.S. House of Representatives resolution states, “If Meucci had been able to pay the $10 fee to maintain the caveat after 1874, no patent could have been issued to Bell.”

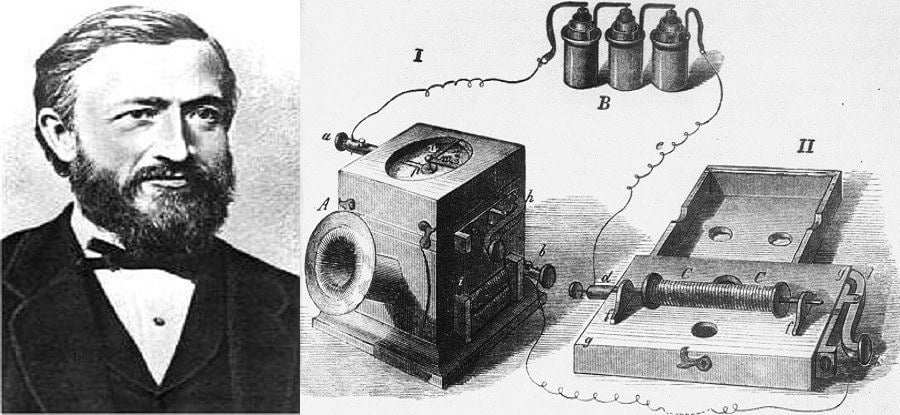

Left: Johann Philipp Reis. Right: Reis’ drawing of his telephone invention. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons.

Even Meucci’s claim obscures the work of Johann Philipp Reis, who constructed an electromagnetic device that transmitted human speech back in 1860. However, the sound quality was relatively poor and the device wasn’t commercially practical. Nevertheless, the first words transmitted electromagnetically by a device we could call a telephone weren’t Bell’s immortal “Mr. Watson — come here — I want to see you.,” but instead Reis’ test phrase, chosen for its sonic characteristics in the original German: “The horse doesn’t eat cucumber salad.”

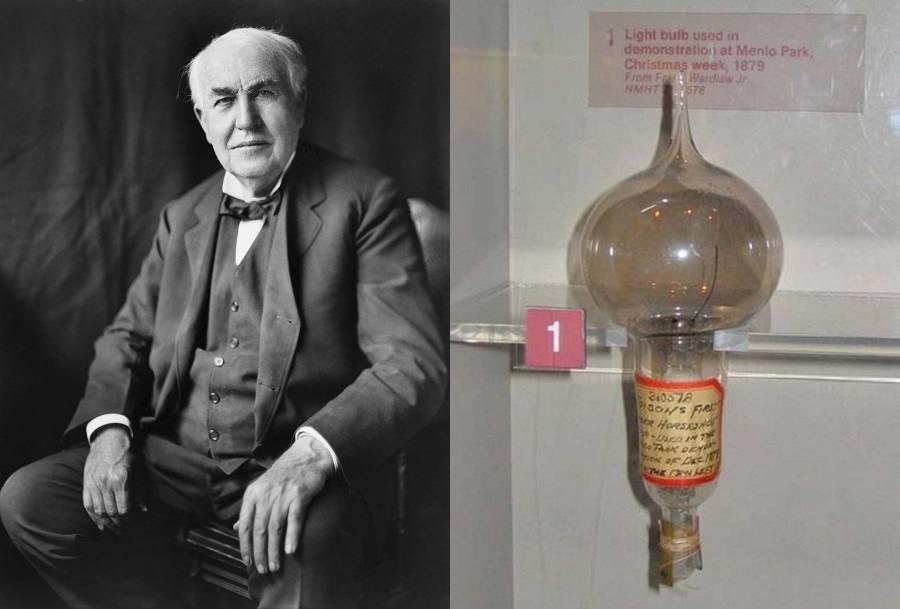

Famous Inventors: Thomas Edison Didn’t Invent The Lightbulb

Left: Thomas Edison, another of history’s most famous inventors. Right: The light bulb Edison used at hist historic first demonstration on December 31, 1879.

Why He Got Credit

On October 22, 1879, Thomas Edison, certainly one of America’s (and perhaps the world’s) most famous inventors, successfully tested an incandescent light bulb (in which an electric current heats a wire filament to produce light) for 13.5 hours. One month later, the patent was his and the world was never the same. His basic design still brings light to most of the world over 100 years later.

Who Actually Deserves Credit?

By now, the notion that Thomas Edison didn’t actually invent the light bulb is one of those bits of revisionist history that’s become so widely accepted that it’s virtually crossed over into the mainstream. And why not? Even the most cursory look at the facts reveals that a whole host of inventors across various countries had achieved incandescent light as much as 80 years before Edison.

Edison defenders will claim that those dozens of working incandescent lights before Edison’s are of little practical merit because they either couldn’t stay lit for any worthwhile amount of time, or were completely impractical for mass use either in their design or their cost. And on that count, Edison’s defenders are right. A device that throws off light just a few feet and stays lit just a few minutes isn’t a light bulb — not really — and was never going to change the world.

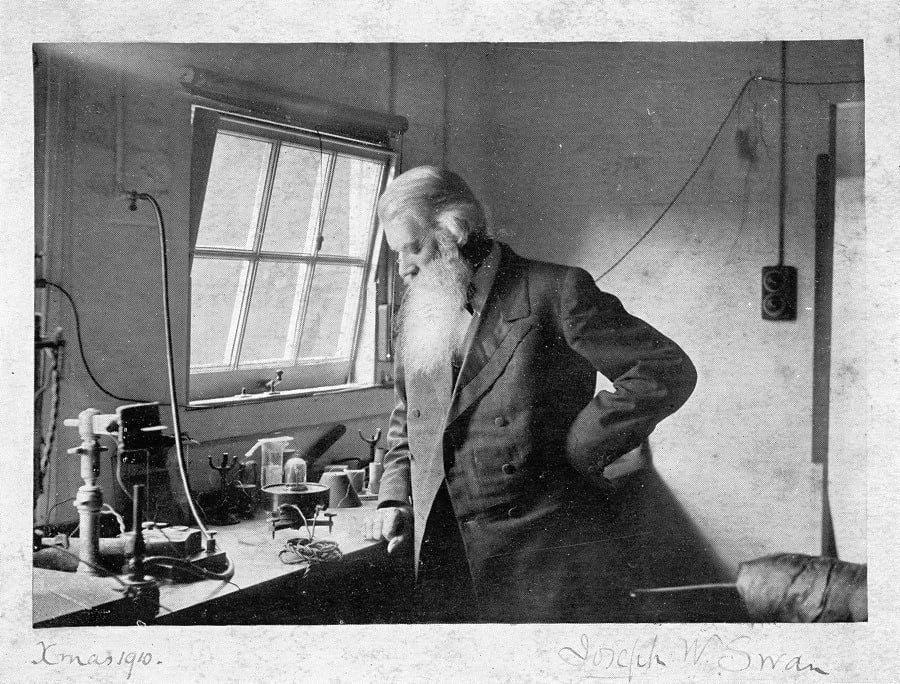

That defense, however, doesn’t explain away the work of one man: Joseph Swan.

Joseph Swan. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

By the time Edison was developing his bulb, the template, based on the work of dozens of others who’d come before, was already in place. You needed a glass bulb, a vacuum to suck the air out of it, wires to supply the charge, and some kind of rod or strip to take that charge, heat up, and actually supply the light. That last bit was the most important, and the trickiest.

Most tried to use platinum as the material for that rod. It could take the heat well, but, even after decades of refinement and dozens of tries, couldn’t burn bright enough or last long enough. So it was that the person who could make the right rod would be the one to save the day.

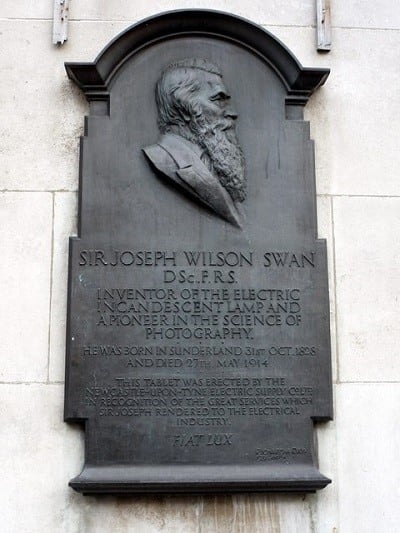

Public plaque commemorating Swan as the inventor of the incandescent electric light bulb, located in Newcastle upon Tyne, where Swan first demonstrated his bulb in 1878.

And the right rod was finalized, ultimately, by Edison, but wouldn’t have been possible without one of history’s less famous inventors, Joseph Swan. The solution to the rod problem was using carbon, and Swan was the one to know that as far back as the 1850s, far before Edison.

At that time, the vacuums weren’t strong enough, however, so he put his experiments on the back burner. But in the 1870s, when the vacuums were finally adequate, Swan went back to work and brought his carbon bulb to life.

Starting in late 1878, almost a full year before Edison, Swan began publicly demonstrating his carbon bulb. Yes, his carbon rod was too thick and thus didn’t last very long, and yes, Edison filed his patent just before Swan eventually found an even better rod than Edison’s, but the Edison bulb, apart from that thinner rod, was virtually a copy of the Swan bulb.

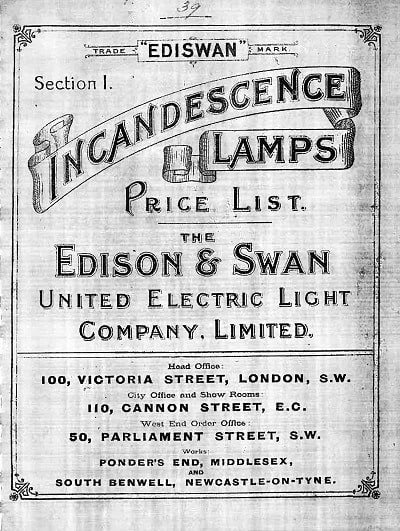

A price list from the Edison & Swan company that Edison was required to form after British courts found his design to be practically the same as Swan’s. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The courts in Swan’s native Britain backed Swan’s claim to the bulb, allowing Edison to sell bulbs there only if he joined forces with Swan. And while Edison’s thinner rod made the difference at first, it was soon Swan’s cellulose rod that truly won the day and became the industry standard that would bring light to the world.

The one final — endlessly intriguing — piece of the puzzle is John Wellington Starr. He and his partners obtained a patent for a bulb using a carbon rod all the way back in 1845. But he died the following year and the mechanics of his bulb were just different enough from Swan’s, rendering him, unfairly or not, a non-factor in the Swan/Edison showdown.

Neither Nikola Tesla Nor Guglielmo Marconi Invented The Radio

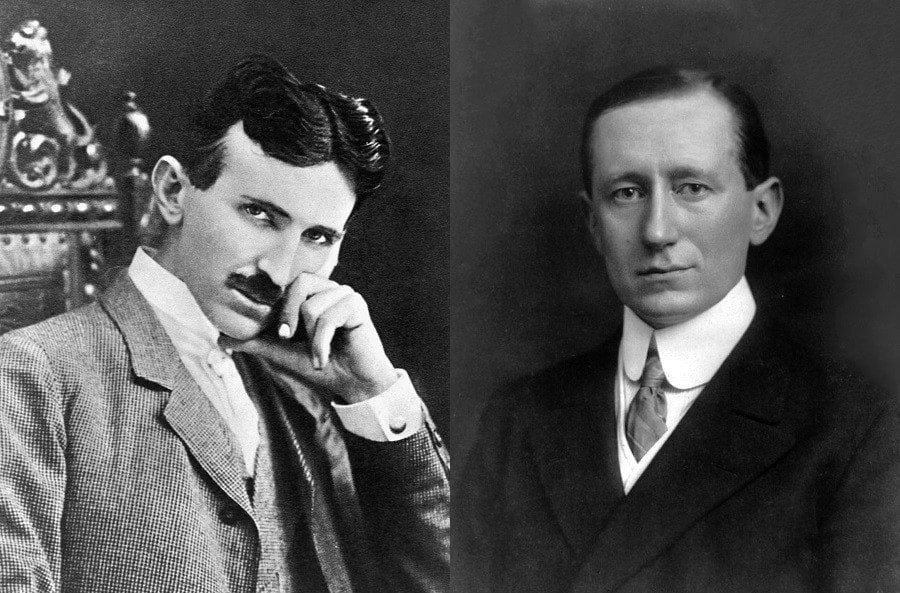

Left: Nikola Tesla. Right: Guglielmo Marconi. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons (left), Wikimedia Commons (right).

Why They Got Credit

The most common version of the story states that Guglielmo Marconi invented radio. Marconi did indeed build the first successful apparatus for the long-distance transmission of radio signals, sending honest-to-goodness signals several times during public demonstrations between 1895 and 1897. Soon, he received the first patent in “wireless telegraphy” (as it was then known). He then received a patent in 1904, widely recognized as the one marking the invention of radio. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics for his achievements a few years later. Overall, Marconi’s case is strong.

The most common attack on Marconi’s claim comes from supporters of Nikola Tesla, one of history’s most famous inventors. He invented the now famed Tesla coil, essential in transmitting radio waves, in 1891.

Four years later, he was set to actually transmit radio signals, over a distance of 50 miles, before a fire destroyed his lab. But by 1897, he’d rebounded and filed several radio patents, which were eventually granted in 1900. Over the next three-plus years, Marconi’s radio patents were routinely denied on the grounds that they relied too heavily on the work of Tesla (and a few other inventors).

But in a startlingly rare decision, the Patent Office reversed their decision in 1904 and gave Marconi the patent for the invention of radio.

Many argue that the Patent Office unfairly caved to Marconi because he and his family had many connections among the wealthy and powerful, and because Marconi himself had started making quite a lot of money with his early radios. Naturally, this all paints Tesla as the unsung hero.

Who Actually Deserves Credit?

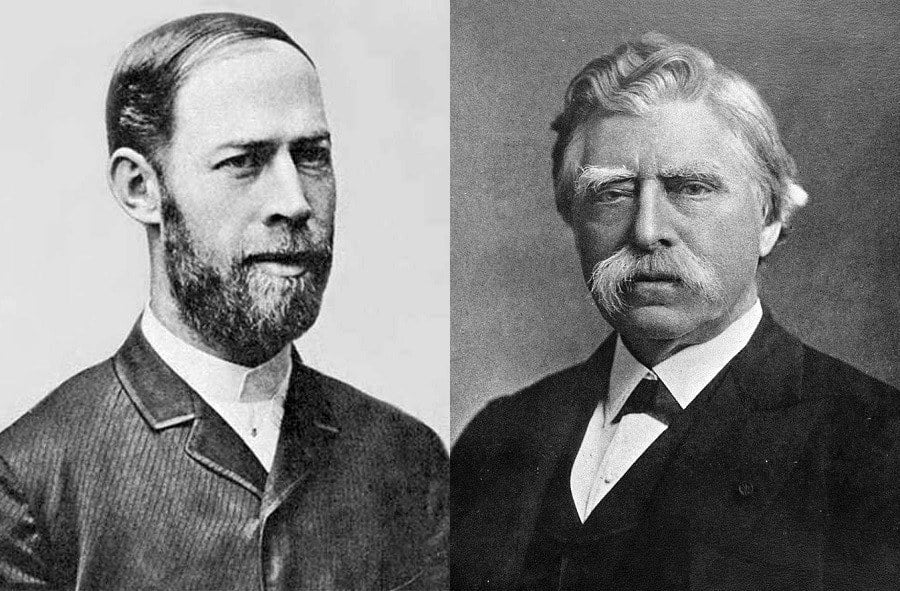

Left: Heinrich Hertz. Right: David Edward Hughes. Neither man ranks with history’s msot famous inventors.

But, once again, the final showdown between the two heavyweights is actually more of a smokescreen hiding the truly pioneering work that came before. Starting in 1886 — almost a decade before Marconi’s public demonstrations — German physicist Heinrich Hertz, seldom recognized as one of history’s most famous inventors, conducted a series of experiments in which he successfully observed and transmitted electromagnetic waves for the first time ever.

One of Hertz’s earliest receivers used to detect radio waves. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

So why didn’t he go down in history like Marconi or Tesla? In short, Hertz’s experiments were far more coldly, abstractly scientific than Marconi’s or Tesla’s. He demonstrated what could be done in a lab, but had no eye toward how these discoveries could function outside of a lab, let alone in the public and commercial spheres. When asked about the ramifications of his experiments and what practical purpose they could serve, he replied, “Nothing, I guess.”

Before Hertz became the first person to conclusively prove the existence of radio waves, it was difficult for other researchers and inventors to know whether or not they may have been transmitting those same waves themselves. Nevertheless, British-American inventor David Edward Hughes seems to have a very strong claim for transmitting radio waves in 1879, seven years before Hertz’s first experiments.

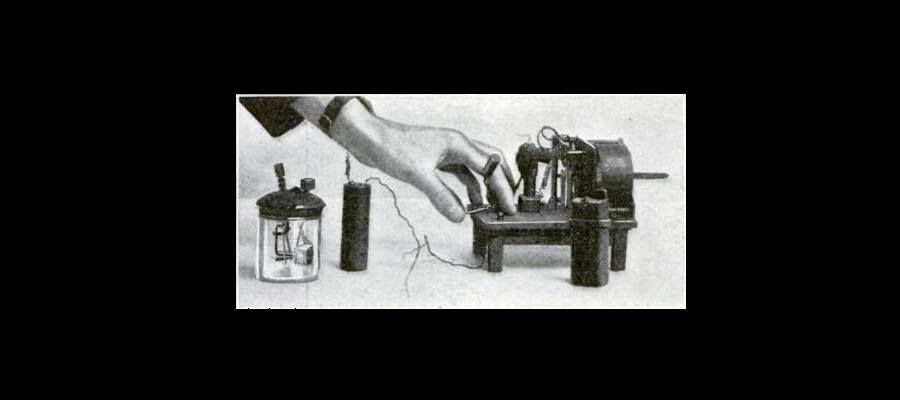

The spark transmitter (right) and microphone (left) that Hughes used to detect radio waves

As was the case with the faulty reed that helped kickstart Alexander Graham Bell’s work on the telephone, Hughes noticed that a spark from a faulty telephone of his could be picked up by a microphone device he’d invented. Soon, his own homemade sparking device could transmit waves to his microphone over a distance of 500 yards — waves that, given the nature of his equipment, almost certainly would have been radio waves.

The esteemed scientists at London’s Royal Society concluded that Hughes hadn’t actually transmitted radio waves, but instead some kind of other, less significant, electromagnetic waves. However, Hughes wasn’t a trained physicist and thus couldn’t sufficiently argue his case, strong as it was. Plus, any official body (like the Royal Society) was quick to dismiss radio waves in the era before Hertz conclusively proved their existence. Thus, many now claim that the dismissal of Hughes was unwarranted and that he in fact deserves credit for inventing the radio.

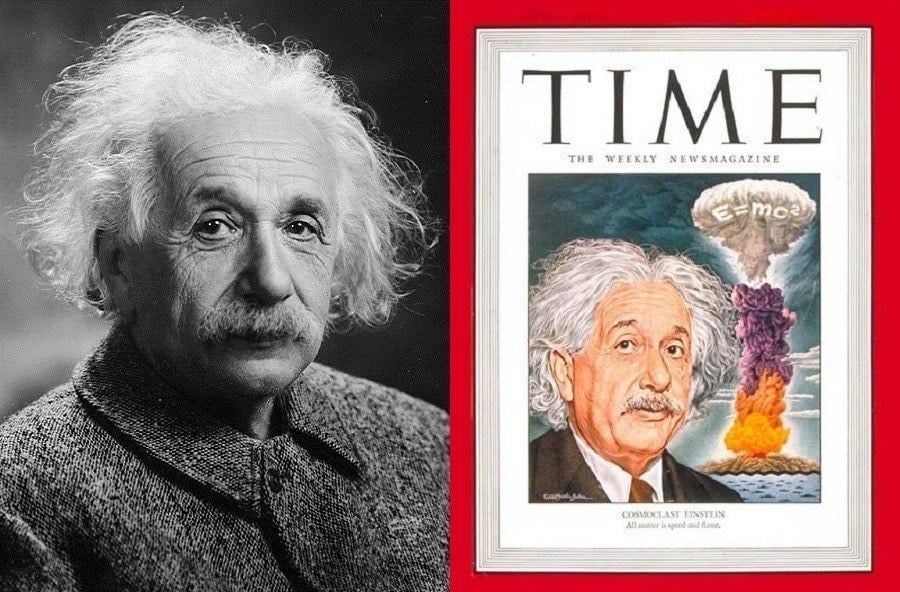

Einstein Didn’t Invent E=mc2

Left: Albert Einstein. Right: TIME Magazine paces Einstein and his famous formula on its cover. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons (left), Wikimedia Commons (right).

Why He Got Credit

For anyone who’s not a physicist, the biggest blip that physics makes on your radar is when you take it in high school, then forget it. So it’s actually quite strange that everyone knows E=mc2 (and can probably tell you what those letters stand for). And everyone who thinks about E=mc2, then thinks about Albert Einstein.

There’s no reason not to. Every authoritative body and publication you could ever name gives Einstein the credit, and he did indeed publish the equation for the first time in his landmark 1905 paper Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?, forever laying claim to the groundbreaking idea that all mass contains a certain amount of energy relative to that mass and vice versa.

Who Actually Deserves Credit?

What you didn’t know about that paper was that it was merely an addendum to a paper he’d published earlier that year, making E=mc2, in the words of pre-eminent physicist Brian Greene, “the most profound afterthought in the history of science.” Nor did you know that Einstein didn’t actually prove the equation, nor did he even write E=mc2, but instead wrote it as m=E/c2.

Left: Friedrich Hasenöhrl. Right: Oliver Heaviside. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons (left), Wikimedia Commons (right).

While that formula is 100% equal to the E=mc2 we all know, it’s helpful, when investigating who truly invented the formula, to think about it the way Einstein originally wrote it. That’s because, in its m=E/c2 form, the bones of that equation had existed for years before Einstein. Both English physicist Oliver Heaviside (in 1889) and Austrian physicist Friedrich Hasenöhrl (in 1904), building on the theories of nearly a dozen other men, had published versions of the equation that boil down to m=(4/3)E/c2.

Now, m=E/c2 obviously isn’t the same as m=(4/3)E/c2. But that latter equation, though nowhere near as famous, actually holds true under a number of conditions (such as with the mass of classical electrons), just not conditions that have anything to do with the life of the average person in an observable way.

And that’s just it. The 4/3 equation matters to physics, but not in a way that the average person can appreciate. Einstein’s version of the equation took hold because it was simple and universal, with pleasing assonance to boot. It’s probably no coincidence that the world’s favorite equation, other than that tiny little 2 at the end (which is technically an exponent), doesn’t actually have a number in it.

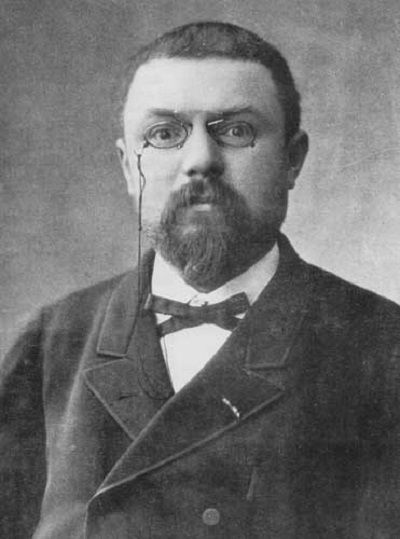

Henri Poincaré. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, in the big picture, neither physicists nor laymen are actually interested in E=mc2 for the numbers. They’re interested in the supposed groundbreaking imagination behind it, the wild, world-changing idea that mass and energy had some kind of equivalency. And that part — which really was the most important part of the equation — had been formulated by Heaviside, Hasenöhrl, and especially French physicist Henri Poincaré years before Albert Einstein.

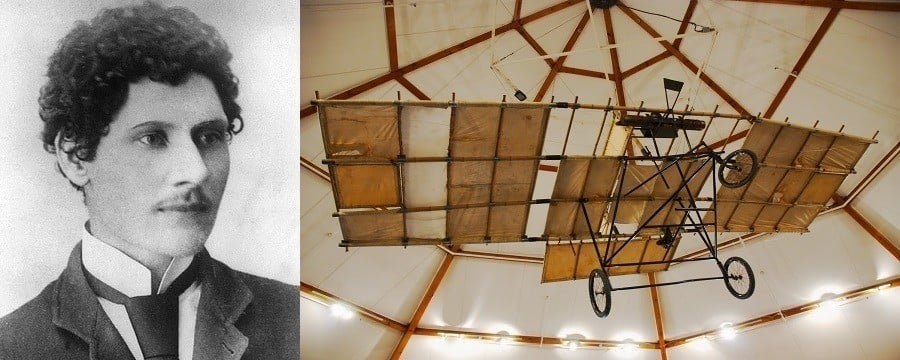

The Wright Brothers Weren’t First In Flight

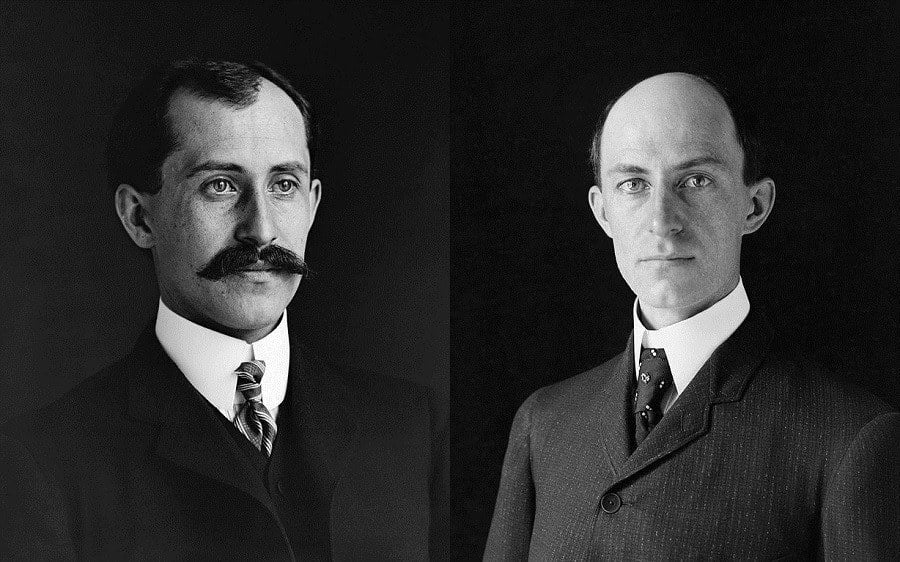

Famous inventors Orville (left) and Wilbur Wright.

Why They Got Credit

The story goes that on December 17, 1903, in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, famous inventors Orville and Wilbur Wright were first in flight. Indeed, at 10:35 a.m., Orville piloted their aircraft for 12 seconds, flying about 120 feet at about 10 feet off the ground. The historic moment was witnessed by five other men and photographed with striking precision.

The famous photo taken during the Wright brothers’ very first flight, with Orville piloting and Wilbur running alongside.

It wasn’t long before the brothers were international celebrities and anybody with any authority (particularly U.S. government bodies, across the board) declared them the first to fly. To this day, their original aircraft sits in the Smithsonian Institution, proudly displaying that declaration.

Who Actually Deserves Credit?

When it comes to “first in flight,” you’ve first got to unpack that notion and agree on the specifics. You’ve probably already implicitly understood the designation to mean that the flight had to be mechanically powered, that it had to be manned, that it had to be heavier than air, and that it had to truly launch and truly fly — that is, leave the ground and stay above the ground at the will of the person controlling it, not simply vault upward and stay in the air as long as that initial vault allowed.

Those criteria eliminate dozens of men from the running, men who had become airborne and technically flown decades before the Wright brothers. But once you weed those men out, three remain.

Clement Ader. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

First, Clément Ader flew a bat-like, steam-powered aircraft all the way back on October 9, 1890. It verifiably took off and stayed in the air over a length of about 160 feet (longer than the Wright brothers’ first flight). It is universally accepted that this was the first time a powered aircraft took off from level ground, but the question lies with that fourth criteria above.

Ader’s Avion aircraft, an updated, and still extant, model of the craft he flew on October 9, 1890. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Because no aircraft, in that era, could stay above ground for very long at all, it was difficult to discern whether a craft had flown or hopped, whether it could have stayed in the air longer if only its control and power source were better or if it was simply a glorified jumper. The jury remains permanently out on whether Ader truly flew or merely hopped.

Gustave Whitehead. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

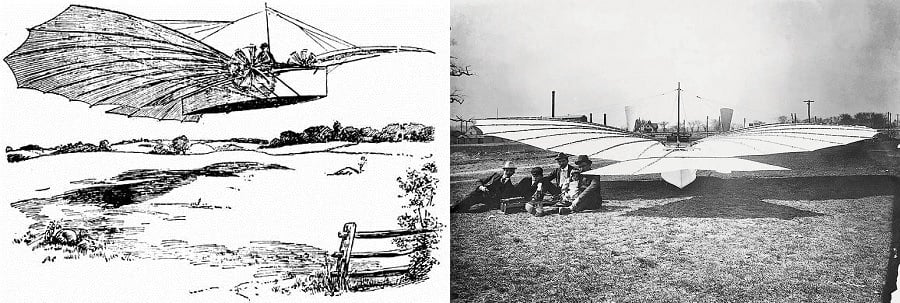

Next, on August 14, 1901, Gustave Whitehead — unlike the Wright brothers, not one of history’s more famous inventors — was reputed to have flown a powered, heavier than air machine in Connecticut. By all accounts, this flight met all the necessary criteria. It just comes down to whether or not you believe those accounts.

Left: The original Bridgeport Herald newspaper illustration accompanying the report of Whitehead’s August 14, 1901 flight. Right: The plane that reportedly made the August 14 flight. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons.

The story was first printed by a local newspaper and was then reprinted by several other, larger papers in major cities (including New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C.). A number of alleged eyewitnesses and respected publications have since thrown their support behind the story — to this day — but, to doubters, this one remains a very compelling case of he said, she said.

Left: Richard Pearse. Right: A replica of the plane Pearse supposedly flew, now on display in the South Canterbury Museum in Timaru, New Zealand. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, on March 31, 1903, just months before the Wright brothers, Richard Pearse (who you’ll never find on a list of famous inventors), an all-but-forgotten farmer and amateur aviation pioneer living in rural New Zealand, supposedly flew.

Over 20 alleged eyewitnesses say it happened, a handful of governmental and otherwise official bodies in New Zealand back the claim, plenty of books and established media outlets have run with the claim, and parts of the plane have been found. But given Pearse’s reclusive nature, the tiny rural community he hailed from, and the lack of bulletproof physical evidence, it was easy for him to be overlooked.

Michael Jackson Didn’t Invent The Moonwalk

Why He Got Credit

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQMSv9GE68U

When the biggest pop star in the world is at the biggest point in his career on one of the biggest stages he’s played, and he unveils a mind-blowing move that would become his signature, no one questions who may have done that move before — and it’s hard to blame them.

Who Actually Deserves Credit?

That’s Bill Bailey moonwalking at New York’s Apollo Theater in 1955. And while that might be the oldest extant recording of a moonwalk, the dance was reportedly performed countless times by dozens of famous entertainers (including Marcel Marceau, James Brown, Dick Van Dyke, Cab Calloway, and many more) as far back as the 1930s.

The thing is, while we all gave Michael Jackson credit for the move, he’d scarcely deny that it wasn’t really his. The evidence is pretty solid that Jackson knowingly sought out Shalamar’s Jeffrey Daniel to teach him in the move in the early 1980s.

After this look at famous inventors, check out the war inventions you use every day, and history’s strangest inventions. Then, discover some Leonardo da Vinci inventions that changed history forever.